July 25, 2018

Research shows that economic pressure pushes drivers to work extremely long hours, contributing significantly to truck crashes.

A 2010 survey by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health showed that, on average, long-haul truck drivers work 50 percent more hours than typical workers and regularly violate U.S. regulations limiting commercial driver work hours for safety reasons.

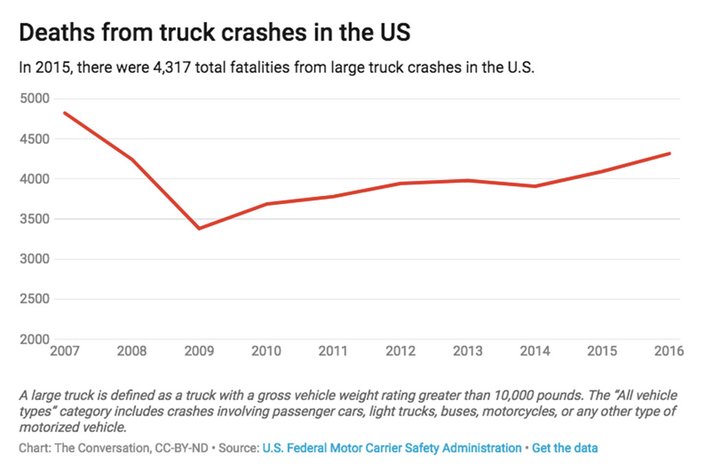

Long working hours and intense economic pressure are important to everyday motorists, because the truck driver’s workplace is everyone’s roadway. Trucking casualties claim not only the lives of truck drivers, but a significant number of other roadway users – pedestrians, bicyclists, and automobile drivers and passengers. In 2015, 3,836 people lost their lives in heavy vehicle crashes in the U.S.

My team’s research, as well as numerous other studies, shows a strong link between pay and safety. We calculated that, at 60 cents per mile, truck drivers will trade labor for leisure, working fewer hours and thereby reducing crashes and improving highway safety.

In one study, we looked at the University of Michigan Trucking Industry Program truck stop-based driver survey of 573 mostly long-haul truckers.

Most truck drivers do not get paid for loading, unloading and other delay time, so they regularly record that work time as “off duty,” conserving their available work hours and allowing them to extend their work week. Because this work time goes unpaid, cargo owners feel free to waste this time, costing American truck drivers more than $1 billion per year. The Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Transportation finds that each 15 minutes of excessive delay time increases the average expected crash rate by 6.2 percent.

Truckers log this unpaid labor as off-duty so that they can drive more hours during the week. Indeed, the long-haul truck driver survey shows that more than half of all U.S. truck drivers exceed the weekly limit of 60 hours per week. One in 5 of these drivers work more than 75 hours per week.

In addition to long hours and low pay, truck drivers face dangerous workplace pressure. My study looked at the U.S. Large Truck Crash Causation Study of more than 1,000 truck-involved crashes. This study shows the last action that a driver took – such as failing to brake for stopped traffic – before the crash. The data suggests that fatigue and driver aggressiveness – in addition to the already substantial economic pressure – make it significantly more likely that the truck driver is responsible for the crash.

There are no good public data on mileage rates. However, according to one private survey, the average dry van truck driver with three years experience made 35 cents per mile in 2010. Wages have gone up since then and may be about 40 cents now, but this is in an unusually tight labor market. No matter how you cut it, wages are far lower than the predicted “safe rate” or safety wage.

In Australia, the Transport Workers Union has called on the government to increase truck driver safety by increasing rates. This month, they asked the federal government to reintroduce a road safety watchdog that would mandate minimum wages and working conditions for interstate truck drivers.

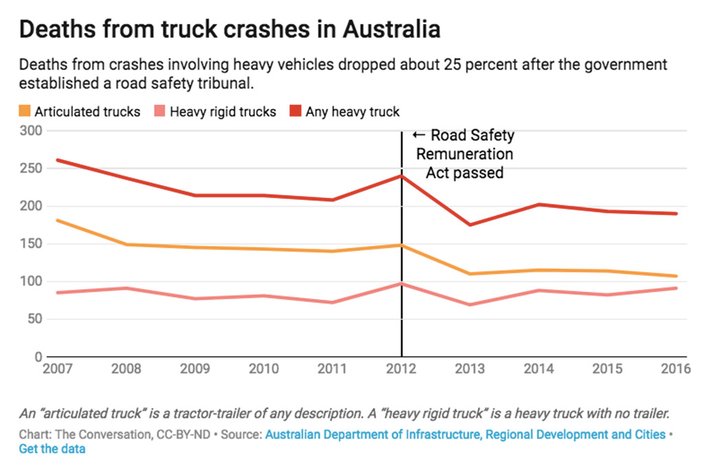

Australia actually once had a road safety watchdog, the Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal, but that was scrapped in 2016. The government decided to kill it based on a private consulting report that claimed that the link between pay rates and safety was bogus.

However, the report actually showed a 50 percent decline in fatal heavy truck crashes after the tribunal was established in 2012, failing to quantify the benefit of the approximately 25 percent decline in the number of deaths.

Safe rates are not just an Australian or American problem. In 2015, trucking employers, labor organizations and 25 governments signed a tripartite global consensus agreement at the International Labour Office in Geneva, Switzerland. All parties agreed that low rates paid to truck and bus companies and their drivers contributes to unnecessarily dangers on the world’s highways, pledging to conduct further research on the problem.

![]() In my view, a “safe rates” program – raising pay rates by about 50 percent and paying drivers for all working time – would go a long way toward reducing this risk and the cost borne by victims of crashes.

In my view, a “safe rates” program – raising pay rates by about 50 percent and paying drivers for all working time – would go a long way toward reducing this risk and the cost borne by victims of crashes.

Michael Belzer, Associate Professor, Economics, Wayne State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND/Source: U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND/Source: U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND/Source: Australian Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND/Source: Australian Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities