February 23, 2015

David J. Phillip/AP

David J. Phillip/AP

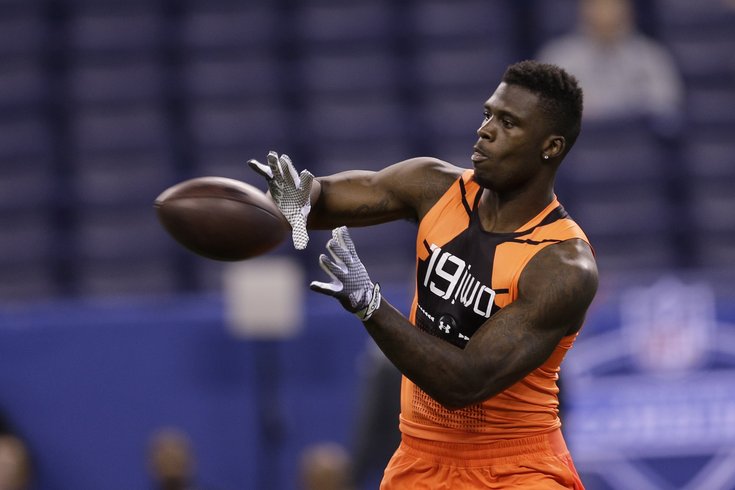

Missouri wide receiver Dorial Green-Beckham runs a drill at the NFL Scouting Combine Saturday in Indianapolis.

INDIANAPOLIS — The questions were similar, and Dorial Green-Beckham had virtually the same response for each one.

"I'm disappointed in myself for all those things I did at Missouri," said the wide receiver, who spent last season on the sideline in large part because of legal troubles, including allegations that he pushed a woman down a flight of stairs.

Green-Beckham repeated some version of that nine times during the 10 minutes he spent with reporters at the NFL Scouting Combine last week. He could have said it 100 times, and it wouldn't have answered — or ended — the questions.

Because of the domestic violence scandals involving Ray Rice, Adrian Peterson and others that came to light last season, the scrutiny for the receiver with first-round talent but all those character questions is only beginning.

Now more than ever, teams are using the combine not so much to find out what sort of player they're getting — they can watch the tapes for that — as what kind of person they're getting. The 15-minute interviews the teams get with the players, along with tests that evaluate their psychological profile, have never been more important.

"I think we all get overwhelmed with talent and you want to buy into the fact that your building or your organization can change people when most of the time, statistically, it can't," Mayock said.

"It changes with the times," Giants coach Tom Coughlin said of the vetting process. "We are a microcosm of society. We have our problems just like everyone else, and hopefully we will be able to help educate our people about what is not acceptable."

Placing the issue into even sharper focus is the fact that arguably the most talented player in the upcoming draft, quarterback Jameis Winston, has been a fixture in police blotters during an athletically stellar but personally challenging three years at Florida State.

Sexual assault accusations against him while in college didn't result in charges, but his past puts him at more risk under the NFL's new personal-conduct policy, beefed up in the aftermath of the Rice case.

The policy, which calls for a six-game suspension after a first offense, makes clear that a criminal conviction isn't needed for the league to determine players took part in prohibited conduct. The NFL will have its own investigative arm, and the commissioner can use his discretion based, in part, on a player's previous behavior.

"I understand there are some things in college that a lot of people do that they wish they hadn't later on," said Lovie Smith, coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who hold the top pick. "I understand there are a lot of things on his record. We take all the information we can possibly get at this point. It's still early. Right now, we haven't taken him off our list."

Winston's travails have been widely documented, and with the growth of the Internet over the past decade, a few keystrokes are all it takes to discover a player's police record. The teams work with law enforcement and hire their own people to do some detective work — talking to friends, family, high school coaches and others to uncover details about a player's off-the-field behavior.

"I know I made mistakes and I know I have a past, but right now it's about me moving forward and earning the trust of all these 32 teams out there," Winston said.

Can he really move forward? The teams also hire psychologists to analyze tests that help build a psychological profile of all their prospective draft picks.

"I never felt that, as football people, we were qualified to judge whether a person was psychologically prepared to play in the National Football League," said Bill Polian, the former NFL executive who will be inducted into the Hall of Fame this year. "We left that to the psychologist and left it to the professionals. We were guided by their opinions, which were terrific. Then, we added that to our football judgment to get a full profile."

Among those who design the psychological tests are Dr. Mike Sanders of Human Resource Tactics. He said his tests measure mental toughness, respect for authority and work ethic, among other hard-to-quantify aspects. The HRT test given to Aaron Hernandez, the former Patriots tight end now on trial for murder, had plenty of red flags: For instance, he scored a 1 on a 1-10 scale in the category of "social maturity."

"We point out which players may disrupt team activity," Sanders said in a recent interview with Men's Journal. "We use algorithms that take into account past behavior and compare scores with guys who have had problems in the past. We give teams a heads-up."

Draft guru Mike Mayock, a former player who is now an analyst for NFL Network, thinks the decision on Green-Beckham will make for the most "polarizing conversation" of the draft. He was once considered among the top high school recruits in the nation. Based solely on his athletic ability, there's little debate that he'd be a first-round pick. But he's been arrested twice for marijuana possession and once for pushing a woman down the stairs. No charges were ever filed in that case, but the combination of all the problems led to the receiver's dismissal from Missouri.

Given that record, and the current climate in the NFL, Green-Beckham is the truest definition of a high-risk, high-reward draft prospect.

"How do you not mess up? That's your question," Mayock said. "I'm not sure there is a right answer other than being a little more conservative. And I think we all get overwhelmed with talent and you want to buy into the fact that your building or your organization can change people when most of the time, statistically, it can't."