May 08, 2016

Photo courtesy/The Jolovitz Family

Photo courtesy/The Jolovitz Family

Reva Jolovitz and her son, Paul. “My mother is my hero,” says the longtime talker on 94WIP Sportsradio. "My mother is the sweetest, kindest person you’ll ever met. Nothing fazes her."

At 84, Reva Jolovitz is as unassuming as they come.

She’s tiny for a superhero: maybe 5-feet tall, maybe 100 pounds. To this day, you’ll rarely see her eat much.

But to hear her high-pitched pixie voice, with a wisp of a British accent, connotes warmth, joy and laughter. She speaks in precise sentences. You can almost see the punctuation spill out with each word. Indeed, she speaks several languages fluently.

On a day to celebrate mothers, there is much to celebrate about this woman, whose life is a gift, nearly lost as it was as a young girl.

Her children, Paul and Jenna, remember as grade schoolers that as Mother’s Day approached, they would have their turn to tell about a mother who survived incredible odds. Yes, she was an English teacher, but the rest of what they told their classmates – sons and daughters of lawyers, nurses, doctors, accountants and homemakers – tended to be greeted with wary looks.

You wouldn't expect anything different.

Reva Jolovitz had, after all, survived a Japanese prison camp in the Philippines during World War II. She witnessed torture. Suffered measles, whooping cough, malnutrition, dysentery and starvation. Survived a Japanese sniper’s bullet, and the explosions and gunfire that liberated her and thousands of other civilians from various nations imprisoned on Jan. 4, 1942.

"She’s an incredibly positive person, and maybe that comes from when you’ve seen all of the negative in the world as she has that you look for as many positives as you can.” – Jenna Jolovitz, on her mother

After more than three years, she and more than 4,000 other prisoners were rescued on Feb. 3, 1945 by a "suicide squad" sent by General Douglas MacArthur. It came just in time. The Japanese were planning to execute hundreds and hundreds of them the next day.

Today, the vibrant imprint still lies within the little girl who, between the ages of 10 and 13, ran around seeking solace in any small place she could find in the Santo Tomas Japanese internment camp on a Manila university campus.

Reva Jolovitz sees the world through the wonderment of a child’s eyes, despite being bombed by the Japanese, then again by the Americans.

Like many who lived through and somehow managed to endure World War II, she doesn’t view herself as anything extraordinary. The retired mother of two and grandmother of one who currently lives in Bethesda, Maryland, has a tough time convincing those around her otherwise. In many ways, she was a soldier, too, living amid the squalor, the pestilence, finding good in the eye of an inhuman, unbelievable storm.

“My mother is my hero,” said Paul, the longtime sports talk show host at 94WIP.

“My mother never complains about food in a restaurant; she finds the best in everything,” says Jenna, an accomplished comedy writer who worked at Second City with Steve Carell, Stephen Colbert, Tina Fey and Adam McKay.

Reva, of course, sees it differently.

“My parents are the heroes, if anyone is,” she says. “My mother tried to make (the camp) as normal as possible; most of the parents did. My parents never got upset or took anything out on us. That’s what I found extraordinary.”

It might have been avoided.

With war looming, Soloman Feldman, Reva’s father, begged her mother Zena in October 1941 to take herself and the girls – Reva and her younger sister, Helen – to live with relatives in America. But Zena didn’t want to hear it. She was going with her husband.

December 7, 1941 is a date “which will live in infamy” for Americans. It is also the wedding anniversary of Sol and Zena, who lived briefly in Hong Kong, where Reva was born, and then moved to Shanghai. It’s also the date that Zena, Reva and Helen landed in Manila, as part of Sol’s job relocation as a chief accountant for Caltex, also known as Texaco.

“There were always disturbances in the world when we were living in China, and my parents’ lives were always chaotic from the beginning,” said Reva, who was born in October 1931 and was 10 when she arrived in Manila. “My mother was born in Manchuria and my father was born in Moldova, an Eastern European country and former Soviet Republic. Both families ran away. We had heard about the disturbances involving the Japanese. In 1936, we were evacuated on a ship from Hong Kong for three months and came back. They knew war was coming."

The Feldmans’ apartment was on the outskirts of Manila, not far from a United States Navy airfield. It was a world of difference for Reva. She saw a shower for the time. The next morning, Monday, Dec. 8, Sol returned to Pier 7 to retrieve the rest of their belongings, including the new piano they had bought for Reva.

As Sol was unloading the rest of their luggage, sirens went off. Sol ran for his life as Japanese bombs burst the pier into a million splinters.

The bombings became a daily part of their lives. The Feldmans, like everyone else, assumed MacArthur wasn’t that far away. He was. It would take the famous general almost four years “to return” to the Philippines and plan the rescue of Reva and her family.

Still, the Feldmans tried to instill some sort of normality. With the U.S. airfield nearby, that was difficult. Reva and Helen would run up and down from the basement when they heard the air raid sirens. With their home under constant threat, the Feldmans decided to leave and ran into the Maghlens, family friends who insisted they live with them in downtown Manila, one of the most bombed cities of World War II. Reva became very close with Ena, the Maghlens’ only child. They watched movies in Manila wearing gas masks, told that the Japanese had put poison in the bombs, and Reva followed with her ballet and piano lessons.

As American resistance fell, the Japanese army began moving toward Manila. On Jan. 2, 1942, troops captured the “Pearl of the Orient.” For Reva, the war came close to home, when her piano teacher, a dentist, was shot and killed in cold blood on the streets of Manila. On Jan. 4, a shiny black car filled with Japanese soldiers appeared at the house where Reva and her family were staying to pick them up. They were told that they were wanted for “questioning.”

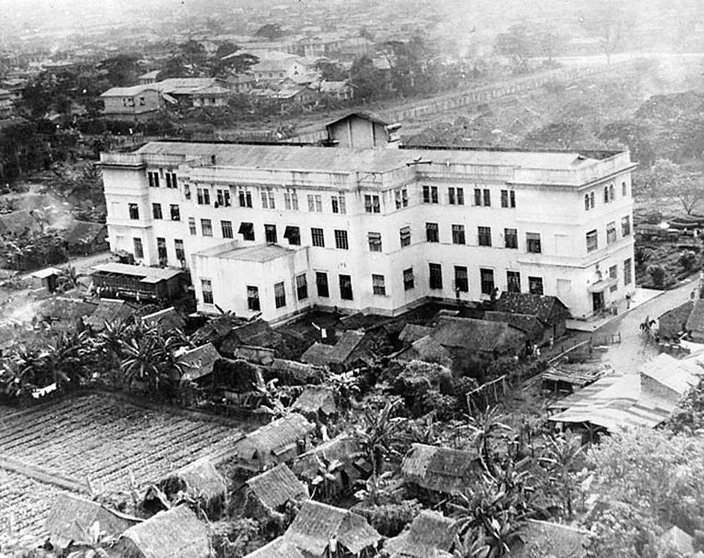

Many of the internees built shanties at Santo Tomas to escape the overcrowded conditions in the dormitories.

“They told us that it would take three days, so we packed for three days, nothing extensive,” Reva recalled. “Helen was left with the Maghlens and they took us to the main stadium in Manila, to Rizal Memorial Stadium. There were all kinds of people there milling around and we were all wondering what was going to happen to us. From there, they took us to Santo Tomas University.

“There were a lot of classrooms and the Dominican fathers had their own residence on the campus. We were ushered into the main building and slept on the overturned cupboards in the classrooms. It became more than three days. It became three years. They crammed about 35 of us in about 4-by-6 feet of space. You had to have mosquito netting, or you would be eaten alive. The room was very full and sort of stuffy, but we had some wonderful people in our room, and a room captain. We had to stand outside every morning, and at night for roll call so they made sure we were all still there.

As time went on, Reva said, it became very difficult for parents to see their children who were left behind. That's when the Maryknoll Sisters intervened to ask the Japanese to bring all of the children left behind to their convent. From there, the parents could be transported by bus from the camp without any chance of escape. The Japanese agreed.

"I was the one they sent to see my sister," she said. "We’re Jewish, but at that time, I wanted to become a nun. My mother used to say it’s funny, because she didn’t know any Jewish nuns. But I loved it. I went to Mass. They were in Latin. I loved the convent. I also got in trouble, because you’re not supposed to talk in the hall and I talked in the hall.”

Many of the Maryknoll Sisters at the Holy Ghost convent didn’t survive when Manila was recaptured by the Americans.

Al Weintraub was with an aviation engineering outfit encamped on Luzon Island in 1945. He volunteered to help liberate the Japanese internment camp at Santo Tomas in Manila.

They were right.

“I just remember my mom was pretty normal; she never lost her temper and I don’t think that my parents were the only ones that were terrific,” Reva recalled. “Think about the chaos around them. They would never take anything out on us. That was the wonder of it all. As I became a parent, I used to frequently think to myself how I would react to a situation like that, with my children always hungry or starving and at the risk of whatever. After that first shipment, the Japanese didn’t allow any more to come through. A tin of corned beef would last five people three days.

“They gradually starved us."

Reva found herself on the brink of adolescence in a domain filled with walking skeletons. Skin hung from people’s bones. She could see her own ribs.

“You learn to live with it,” Reva said. “It’s what everyone went through. In the beginning, we had a lot of banana trees, but a banana takes nine months to mature. As time went on, and things got worse, we took the unripened bananas and my mother would boil them from a stove made out of an old tin can. My job was to cut the tree, slice it up from the outside and test the bark with my mouth to see how far you had to go in to the trunk to find what was edible. People were eating grass, all kinds of things. Dogs and cats disappeared.”

The compound was rife with backdoor bartering. Couples would trade their wedding rings for a cup of sugar. A half pack of peanuts cost $700. Sporadically, the nurses, who were captured from Bataan, would inoculate the children with needles that were like unsharpened pencils.

Through the misery Reva still found time to be a kid.

“I had a gang, the Union Jacks, and there were six of us,” she said. “We would go everywhere together. We had a curfew at 10. We could have movies out on the campus, watch Ronald Reagan and Abbott and Costello. We would have readings and dance performances, before people got too hungry or were too tired to go. I played Dorothy in a play we put on, ‘The Wizard of Oz.’ My Toto was a mop. We put together tin cans to make the tin woodsman. We had dances, too.

"This tall boy taught me how to dance, and there were these two brothers, Paul and David, who were around my age. And Paul was very handsome. I always said to myself, ‘My first child is going to be named Paul, whether it’s a girl or not.’”

This aerial photo shows one of the principal buildings that housed internees at Santo Tomas was the Education building. Shanties and vegetable gardens can be seen near the building and the wall of the university compound is in the background.

Conditions worsened.

By October 1944, the Japanese military took complete control of the camp — and the Americans started bombing Manila.

“The air raids got worse, Christmas came and went, and the air raids got closer and more intense in January,” Reva said. “We taped up the windows so they wouldn’t shatter, and we moved the beds to the middle of the room when the Americans started bombing, and you know what, I wasn’t afraid. We knew help was coming. That was encouraging. But it became harder to go to school, and then one night everyone was sleeping. My mother wanted me to get some water at the shanty. I went out and remember a lady saying to me, ‘Little girl, it’s too dangerous out there.’ I went anyway. The Japanese soldiers were out there screaming at each other and I walked across the campus. They were too distracted to notice me.

“Remember, I was a child; I didn’t have to see my children go through this, like my parents did. It’s why I say my mother and father are my heroes.” – Reva Jolovitz

“I went to my father’s shanty. He was shocked to see me there. I told him, ‘Mummy wanted some water.’ There was an outdoor tap and he was walking me back when a Japanese sentry stopped us. My father told him in Japanese that I had to go to the bathroom. He let us by. I went to the main building and he returned to the shanty where he was staying. My mother was like, ‘Oh, my God, I should have never sent you.’ I told her everything was fine and we all went back to bed.”

The night was Saturday, Feb. 3, 1945.

MacArthur had received word through an informant at the Santo Tomas internment camp that the Japanese were pulling out, but not before executing as many civilians as they could the next day.

Later that same night, Reva felt the ground rumbling under her feet, and the sound of gunfire. This time, it was close. And getting closer.

“There was this tremendous blast and I remember grabbing my little sister and running down the hall, down the main steps and into the lobby, where there was this huge man standing there,” Reva said. “I remember asking him, ‘Who are you, where did you come from?’ He told me, ‘I’m a Buckeye!’ He was probably normal size, but to a starving little girl he was larger than life. I thought he was from the moon. That’s when the U.S. Army crashed through. I looked outside and saw this thing that said ‘San Antone’ and another that said, ‘Georgia Peach.’”

Six U.S. Sherman tanks had come crashing through the Santo Tomas gates. They were from the 44th Tank Battalion - 12th Armored Division, accompanied by 200 men who had volunteered to liberate the compound. In the skirmish, Abiko, the feared Japanese commandant of Santo Tomas, stood up with a hand grenade and was quickly shot down by a U.S. soldier on one of the tanks. The internees got to Abiko and tore him apart.

“I remember him, he always wore this big sword and everyone feared him,” Reva said. “I walked over his body the next day lying in the hall, next to somebody else that had no head.”

The retreating Japanese took 200 hostages and brokered a deal with the Americans, exchanging the hostages’ freedom for their own. But Reva wasn’t exactly free from the turmoil.

Just when food and safety seemed plentiful, her life came within inches of ending.

Gathered in front of the Santo Tomas University's main building in the Philippines, hundreds of internees cheer their release from the Japanese prison camp in February 1945.

Though the camp was liberated, and food in abundance, Reva and a friend went out looking for a big banana tree – out of habit more than anything, she says today.

“We went into the banana trees near the shanty shacks near the Father’s Garden, and I was wearing my favorite shirt that my mother made for me," she remembered. "The bananas weren’t ripe. They’re full of liquid when unripe, and when I opened it, the banana poured all over me like tear drops and stained my shirt. I thought, ‘My mother is going to kill me."

"At that moment, something whizzed past my shirt. Then I thought something else was trying to kill me.”

The bullet was fired by a Japanese sniper disguised as a priest. The next day the occupying U.S. forces found him hiding in the campus monastery, shooting at people.

Still, the Feldmans had one more near-tragedy to endure. Reva’s sister Helen was playing near a U.S. Army truck as it backed out. Helen tripped on barbed wire and the truck backed up over her, crushing her pelvis. The Feldmans wouldn’t be able to leave Santo Tomas until late-May 1945, after Helen healed. Their 37-day journey on a merchant ship to America left them off in Oakland, California, with a destroyer escort.

“As my sister and I got older, we began understanding more about what my mom went through. I get emotional talking about my mom; I can’t help it." – Paul Jolovitz

To this day, Reva carries a fear of thunderstorms and fireworks on the Fourth of July. But though she witnessed humanity at its worst, she’s found a way to stretch the human spirit in ways that are beyond normal comprehension.

“Remember, I was a child; I didn’t have to see my children go through this, like my parents did. It’s why I say my mother and father are my heroes,” explained Reva, who lost 22 relatives in the Holocaust. “Children are very adaptable. I had a mother, I had a father, and I had a sister. I had teachers. That’s the way you lived. I made up a doll and gave it the ugliest name I could think of, Drigetta. She would sit in the hall at the table with her family, while we stood in line for food. I’d imagine her and her family sitting at a table with all kinds of food. She would tell her mother the food wasn’t good and we would take that doll and knock the daylights out of it.

“It’s people like my mother and my poor father, who had ulcers, that made the sacrifices. Could you imagine what it was like having ulcers on an empty stomach? The man was in great pain and he would sit quietly in a corner and tear a handkerchief into pieces. He wouldn’t say anything. One day during the rainy season in the camp, as he was walking back to our shanty by the barbed wire, he didn’t see a ditch and tripped into it. When he grabbed something to hold on to, he wrapped his hand around the barbed wire that ripped his hand. A dear friend’s father died two weeks before we were liberated. I lost friends during the bombings. But you know, I belong to several groups of survivors. It’s over 70 years ago, and the survivors keep in touch with each other.”

For her children, Reva's ordeal gives them perspective on their own lives.

“My mother to this day doesn’t eat, and I think it goes back to her time in the camp,” said Paul, 54, who’s been a sports talk show host at 94WIP for 19 years. “As my sister and I got older, we began understanding more about what my mom went through. I get emotional talking about my mom; I can’t help it. My mother is the sweetest, kindest person you’ll ever met. Nothing fazes her.

"When I think how mad I am at something that’s irrelevant, then I think about what my mother had to go through. I get so mad at myself. It’s why each Mother’s Day means more. She’s the bravest person I know. She doesn’t think she’s brave, because she never brings it up.”

Says Jenna: "My grandmother used to tell me the story when my mother had whooping cough in the camp. At night, she would stay with my grandfather in the shack outside the barbed wire and she would sit up at night and see a Japanese soldier walking up and down. My family told me my mom was never scared.

“My mom told me the story years later how terrified she was. When you’re a kid, you protect your parents by not telling them things like that. My mother internalizes a lot of stuff. When we were young, she would always gather us around the window to watch thunderstorms and how fun they were. I didn’t know until I was older when she told me she was afraid of thunderstorms, but she didn’t want us to be afraid.

"She’s an incredibly positive person, and maybe that comes from when you’ve seen all of the negative in the world as she has that you look for as many positives as you can,” she says.

One night, around Mother’s Day three years ago, Paul had Reva on the air with him. She described her stay in the internment camp, and it turned into riveting radio. As Paul checked off and thanked Reva, his producer motioned for Paul to come back to the producer’s booth during a commercial break.

Someone called in to say they were on that mission to liberate Santo Tomas, the producer told Paul.

“I basically said, ‘Yeah, sure he did,’” Paul remembered. “How many people are alive from that time? Not many, and then how many people happened to be listening to the radio at the exact time I was talking to my mother about a Japanese internment camp? I thought it was some lunatic. He wanted my mother’s number. I took his number and passed it to my mom. If my mom wanted to call, it was up to her, but I let her know some crackpot was calling.”

But Al Weintraub was no crackpot.

Reva called Al and they instantly connected. He proceeded to tell her that he was part of an aviation engineering outfit encamped near the edge of Clark Field on Luzon Island. He had become friendly with some of the guys in the 44th Tank Battalion. He also knew someone who was looking for his aunt and uncle, and they were supposed to be imprisoned at Santo Tomas.

“MacArthur’s people got the word that they were going to execute 1,200 to 1,500 the next day, the morning of Feb. 3, and I saw the tanks rolling,” said Weintraub, 95 today, though his voice betrays his age. A five-time Bronze Star medalist, he is the father of three and lives with his daughter in Drexel Hill, Delaware County.

Al Weintraub, 95, lives in Drexel Hill. He heard Reva Jolovitz talking on the radio about her experience at the Japanese interment camp he helped liberate. He reached out and now he and Reva talk regularly.

“They sent six tanks and 200 men. The tank battalion blew the doors off the gates and the Japanese took a bunch of hostages. I remember I went to the infantry commander and told him that I had to find a couple named John and Winny Giles. He said it would be impossible because they were setting up a roster the next day.

“So when I heard Reva’s story, I had to contact Paul and get in touch with her someway. The conditions in that camp were pretty bad. I was shown a picture of John Giles, the uncle of my buddy. He must have been around 200, 210 pounds in the shot. When I found him the next morning, it was quite a scene. He was around 140 pounds. They starved those people.”

Weintraub, a graduate of South Philadelphia High, now speaks to Reva regularly. He was inducted in the U.S. military on Jan. 11, 1943 and discharged Dec. 15, 1945. He spent 27 months in combat zones, first on Northern New Guinea, then a small island called New Britain, back to Northern New Guinea and then to the Philippines.

“We saw so much, so it was hard to imagine an 11-, 12-year-old girl surviving that camp,” Weintraub said. “You had to understand that these people had a lot of will to remain alive. Each and every one of them in that compound. Every man and woman I found, every child I found, they were all stalwart. They really were. They were a magnificent group that if you were a soldier, you’d be willing to lay your life down for them, too.

“Reva is the real heroine. She gave her parents and other adults in that compound help and hope, because she had a great attitude and she reflects that in the way she carries herself today.” – Al Weintraub

“I was a soldier with a full belly and a gun in my hands. Reva was a little girl half-starved, being bombed every day, first by the Japanese, then by us. You saw things in that camp that made you wonder how anyone survived. When you have to, you find the strength. It’s what is great about this nation. I’m not special. What I did 11 million other guys were doing. Reva is something else. She was a brave, brave little girl, and she’s a brave, brave woman. She was a soldier, too.”

“Reva is the real heroine," he said. “She gave her parents and other adults in that compound help and hope, because she had a great attitude and she reflects that in the way she carries herself today.”

Reva went on to Stanford and graduated with a degree in English, and followed that up with a graduate degree in English from Columbia. Through a mutual friend she met Herb Jolovitz, an Ohio State graduate and a pretty special guy himself whose father passed when he was young and was raised by his mother.

They’ve been married 58 years. They both stay very active physically, Herb goes to the gym daily and Reva goes to ballet class three days a week.

“I love my husband and my children to pieces, though my husband thinks I’m a little crazy,” says Reva, laughing. “My children are their own people. I’m happy that they’ve had an easier life than me. Paul’s wife, Amy, is an angel; Jenna’s given me the gift of a granddaughter and Paul is one-of-a-kind.

"I think when you’ve seen the things that I have, you learn to have a good sense of humor.”

Reva is living history. She should know.

Photo courtesy/The Jolovitz Family

Photo courtesy/The Jolovitz Family U.S. Army Signal Corps/via Wikipedia

U.S. Army Signal Corps/via Wikipedia Photo courtesy/Al Weintraub

Photo courtesy/Al Weintraub U.S. Army/via Wikipedia

U.S. Army/via Wikipedia Carl Mydans, LIFE Images/via Wikipedia

Carl Mydans, LIFE Images/via Wikipedia Photo courtesy/Al Weintraub

Photo courtesy/Al Weintraub