February 09, 2018

Source/Vancouver Coastal Health

Source/Vancouver Coastal Health

Insite, North America’s first legal supervised injection site, opened in 2003 in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The facility operates under a Health Canada exemption from prosecution under federal drug laws. Philadelphia officials visited the facility as it works toward opening one in this city.

Harm is not a simple concept. While it might be obvious to some that drug use comes with “harm,” what that harm is exactly and who is being harmed is rarely discussed. When we enter those conversations we usually start by separating those involved with drugs from the rest of the community.

A group of researchers from the United Kingdom did exactly that when they set out to create a harm-score for various drugs. The researchers separated overall drug-related harm into two categories: harm to users and harm to others. The harm to users included measures of drug-related mortality, damage, dependence and impairment. The harm to others included measures of injury, crime, environmental damage, economic cost, and decline in social cohesion and reputation of a community due to drugs. The results of their analysis found that after alcohol, which by far exceeds any other drug in both overall harm and harms to others, heroin and crack cocaine are virtually tied for second place.

Both heroin and crack cocaine exhibit much higher levels of harm compared to other drugs, however the majority of the harm of either drug is the harm to the user itself.

As a society we place value on preventing harm. Even in the most heinous cases the U.S. Constitution limits the levels of harm – cruel and unusual – that as a society we can inflict. So what do we do with drug-related harm?

In the 1970s, '80s, and '90s black drug users were painted as villains: men as “crackheads,” women as “crack whores,” and youth as “superpredators.” In 2018, white drug users are painted as victims suffering from a disorder.

In the 1980s, when the crack epidemic consisted of black drug users, America’s answer to that question was punitive measures against drug users, who were criminalized as people who inflict harm on others and ignore completely the harm that drugs inflict on the users. Now that white users are dying from injecting black tar, suddenly harm to the users matters.

After decades of punitive actions against drug users, as the epidemic became white, the life of drug users became worthy of saving.

It is estimated that the number of drug-related overdose deaths in Philadelphia in 2017 was 1,200. More than 60 percent of those who died are white. The majority of overdose deaths in 2016 was of white residents as well. That doesn’t mean that communities of color are not suffering from the overdose crisis. Last year, only up through September, 177 black and 115 Hispanic Philadelphians died of drug overdose.

In the 1970s, '80s, and '90s black drug users were painted as villains: men as “crackheads,” women as “crack whores,” and youth as “superpredators.” In 2018, white drug users are painted as victims suffering from a disorder.

That is racism and white supremacy functioning in all their power.

Drug users, regardless of race, are victims of a chronic relapsing disease of the brain, according to the medical textbook. The biology of the disease is the same. The social construct of race and the power of whiteness makes it as such that America only defines the disease correctly when the patient is white.

Abraham Gutman

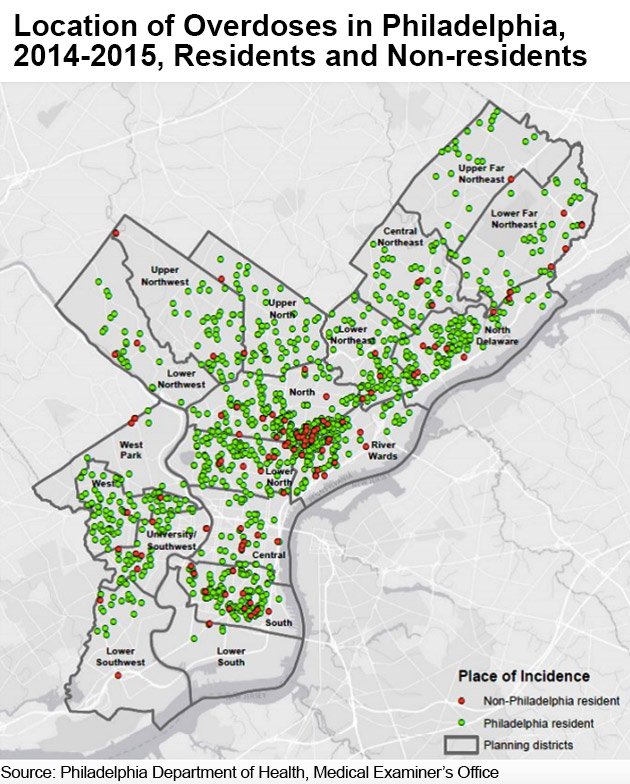

A map of drug overdose death of Philadelphia residents in 2014-2015 (see below) reveals that in almost every neighborhood in Philadelphia people are dying of drug overdose. Many people ask where should these sites be. My response: every neighborhood.

It is time to have a conversation about the drug overdose epidemic that takes into account the harm for all drug users and for others. This includes being honest about the legacy of the War on Drugs in black communities across the nation and about the racist hypocrisy of the “wave of compassion” to white drug users. Perhaps it is also the right time for the city to formally apologize for the way it treated drug users of color up to the recent present.

We must advocate for evidence-based practices that will save the lives of black, white and Hispanic users.

The plan to open safe-injection sites must remember the history and the present of the further marginalization and dehumanization of drug users of color. As such, there must be a process that engages the community (of users and not users) and ensures that drug users of color will be comfortable using the sites.

If we open sites that only benefit white drug users, we will allow the color line to dictate whose life is worthy of protecting from harm and whose isn’t. Nothing in American history suggests that a policy that seeks to be “race neutral” with the philosophy that “a rising tide lifts all the boats” will no be de-facto segregated and discriminatory.

The time for harm reduction is now, and it must mean deliberate and conscientious efforts to reduce harm for all.

• • •

Abraham Gutman is an Israeli freelance writer currently based in Philadelphia who focuses on Israel/Palestine, race in America and policing. He holds a master's degree in economics from Hunter College, where he did research on stop-and-frisk policies, and works at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University. His Twitter handle is @abgutman.

Source/LinkedIn

Source/LinkedIn