September 04, 2024

Provided images/Bold Type Books

Provided images/Bold Type Books

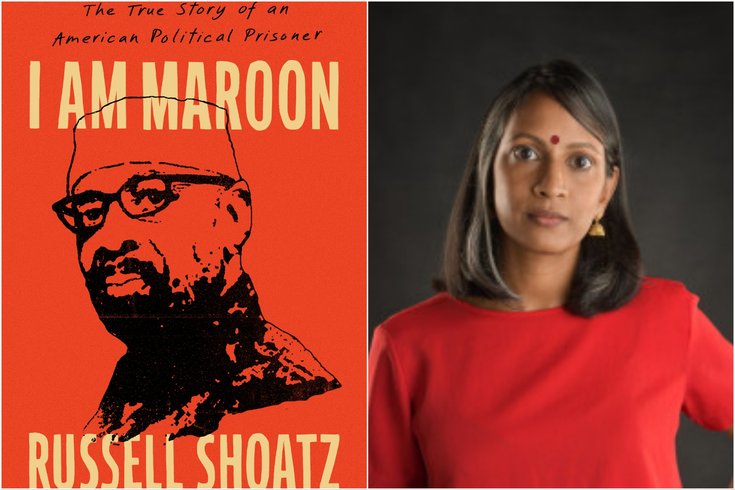

Kanya D'Almeida (right) collaborated with Black liberation activist Russell Shoatz on his memoir 'I Am Maroon,' released Tuesday. Shoatz was imprisoned for nearly 50 years for the murder of a Philadelphia police sergeant. He escaped twice.

In the winter of 1980, Russell Shoatz escaped from the Farview State Hospital, the former Wayne County maximum security institution for the criminally insane. It wasn't the first time Shoatz had busted out of prison — he also fled SCI Huntingdon in 1977, spurring a nearly monthlong manhunt — but it would be the last.

Shoatz spent the next 41 years behind bars, including two consecutive decades in solitary confinement. Nicknamed "Maroon" after the enslaved Africans who sought freedom, he was known not just for his daring escapes but his lifelong work in the Black liberation movement. His case attracted the attention of activists who, along with his children and lawyers, pushed for his freedom. He was granted compassionate release in October 2021, dying two months later.

His life is now immortalized in "I Am Maroon: The True Story of an American Political Prisoner," an autobiography co-written with Kanya D'Almeida. The book is the culmination of years of interviews, letters, research and collaborative revisions of Shoatz's original 280-page manuscript — all conducted while he was imprisoned.

"Yesterday was pub day and I was alone," D'Almeida said. "And I just sat down and cried because it's been so much of my life. It's been so many, many years, and so much work and labor, and not always supported, on any side of it."

The various sides of it include those who see Shoatz as a cop killer; he was convicted of the 1970 murder of Frank Von Colln, a Philadelphia police sergeant, after a deadly shootout at Cobbs Creek Park. Shoatz spends no part of the book arguing his alibi, innocence or involvement in the crime, maintaining instead that he was a prisoner of war in his struggle against the United States. This struggle was taken up by the various groups he founded or collaborated with, including the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party and Black Unity Council.

D'Almeida also struggled to find win over some of Shoatz's family, who regarded her with "understandabl(e)" skepticism on her early visits to Philadelphia. Even people in her home country, she says, didn't "necessarily understand the history of the Black liberation movement in that way." The author had her own doubts, especially as her subject praised the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in early conversations. D'Almeida had grown up "sickened" by the violence between the government and the militant Sri Lankan group.

Over many hours of conversation in Pennsylvania prisons, however, the pair found common ground. After D'Almeida learned she was pregnant, she moved back to Sri Lanka with her husband — who had also edited a book of Shoatz's essays — and pledged to complete the book before she gave birth. Her son was born days after she wrote the final page. Shoatz died shortly after giving his approval.

Now, a dozen years after the project began, his memoir is in bookstores. D'Almeida discussed with PhillyVoice the collaborative process, wrestling with the tougher aspects of her subject's life and how her view of the story has changed since becoming a mother:

I know you talk about this a bit in your preface for the book, but I was hoping you could tell me more about your writing process. How did you go about weaving what Russell had already written in with all your conversations and research?

There was so many drafts of this. I think the short answer is that the draft that became the book as it is now, I really wasn't able to write in its form until I got back home to Sri Lanka. Because I had been living in the U.S. for a long time. I had been in the States since 2006, and it was only when I found out I was pregnant that I went back home to have the baby. And I mentioned this in the preface, but that sort of gestation period that I was in, in Sri Lanka, people call it the confinement period. And I just found that that time with no other voices in my head, and actually not even any contact with Maroon himself, was what actually enabled me to do it. ... In that six-month period, I just had everything, all of the drafts of his original manuscript. I had all of the research that I had accumulated, from 2012 onward. And I just sort of spread it out and just worked through it in the chronological order that it currently is in the book.

What was it like writing for and as someone else who was not a fictional character but a pretty well-known political figure?

We spent a lot of time getting to know each other. And then we also spent a lot of time kind of losing the boundaries of what exactly it was that we were doing. Because when I got really into his campaign, I was already in this position where I was having to speak on his behalf. ... And then, especially when we were doing campaigns that involved pressing people to apply pressure on the prison administration, we were really speaking for Maroon in that way, demanding his freedom. The campaign was never a question of saying, OK, this man was wrongfully incarcerated or he's innocent, please let him out. Or he's old. It was always a question of he's a political prisoner and he's being punished for his political views and he's organizing within the prison. So we were always sort of trying to bring those politics out in our speech and what we talked about and in the literature that we created for the campaign.

So all of that had been going on for so many years. And then when we would correspond, it was a lot of times snail mail because I was not allowed pen and paper in our visits. ... And so sitting with those letters, sitting with his physical handwriting, sitting with the pages, I think maybe helped bring our voices together in some ways.

And then I suppose I took a lot of liberties. I took a lot of what he had written, and then I would bring research that I was writing to it, and then send him a draft of let's say a chapter. And he would say, this is great. Or he would make a change, or sometimes he would say, I wouldn't really say it like that. Literally down to the sentence. We had sort of been negotiating that from the beginning. And I would say too, I mentioned this in the preface, but we misunderstood each other a lot. We had to get over a lot of huge cultural misunderstandings, generational misunderstandings. Just the way we each use the English language is so different. I'm from this post-colonial British education system. Maroon was educated in the United States, he has the language of the streets, he has the language of the movement. So we didn't understand each other a lot. And because I needed to understand him in a specific way, we sort of had to pare down language a lot to really be sure that we each were understanding what the other person was saying.

I asked a lot of naive questions because I couldn't be afraid to look stupid in front of him because I did need to understand. So I think we really worked through language in a very tactile way because that needed to happen for us to be able to do this project together.

Was there ever a worry on your part or on his, or maybe from his family, that you two were the best match for this project? Was there any sort of wariness you had to overcome in that regard?

Yeah, definitely. That was the first thing that we wondered when we saw each other. And when we started getting into the nitty gritty of what it is that we each knew (about) where the other came from. Maroon was very interested in the history of Sri Lanka, and I had never met an American who knew as much as he did about the civil war. He literally knew the names of the generals in the separatist militant outfit that was running the north part of the country, which even I hadn't learned until very recently.

And at the same time, he didn't realize that me growing up in Sri Lanka and the generation that I did, that I knew what I did about the U.S. civil rights movement, which was what our father taught us. We used to have that photo of the U.S. athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos on the podium in the Black power salute. ... For us, the Black Power movement, the Black Panthers was a very righteous movement. And it fit with our context of understanding anti-colonialism and all of that from where we lived.

But what I didn't understand was that for Maroon, the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) in Sri Lanka, which we always saw as a terrorist group, was similarly a righteous movement. We clashed on that a lot because I was thinking, wait, no, don't compare yourself to the tigers. Y'all are the Panthers. Y'all are the good guys, fighting the good fight. ... Those kinds of things we really had to battle it out and then have to explain that to other people, right? That, look, we found these points of intersection, of our histories, maybe where we can connect and understand each other. But mostly what other people saw, I think, was the gulf between us. I was young. I didn't really have the knowledge of American history that I have now after a decade of intensive studies. So we had to negotiate that a lot.

I don't know if he told me really the extent to which he spoke up on my behalf. I found myself having to be in a slightly defensive position a lot of the time. Even when I traveled to Philly to go to the libraries and meet his family, it was always a mix of very welcoming and, understandably, very skeptical of who I was.

The nature of doing this, with him incarcerated and being a maximum security prisoner, we didn't think about it like this at the time, but it just required constant creativity in how we approached one another. I suppose it was like an interpretation project as much as a collaborative co-writing project.

His treatment of women is one of the thornier aspects of the book. I know his ideas evolved, but did you struggle with some of the earlier, more kind of misogynistic chapters of his life?

To be honest, I was very surprised that he had put everything down as he had. I thought there might be a bigger effort on his part to maybe erase a little bit of that history or gloss over it. But he really dwelt on it a lot in the early drafts of his book. There's a lot of detail about this, and I did struggle. I did struggle with it a lot. And I think because he had spent so much time on his own thinking through these ideas, the way that I sort of plundered in and asked my questions was a little off-putting to him. So he also put his guards up, when I queried him in certain ways about domestic violence and the strife in his marriage and around his children.

Eventually, once we started to really, I think, understand each other a bit more, he started to write to me at length about it. He didn't like to talk about it as much in person, but he wrote me a lot of letters on this subject, which I still have. And those were huge keys for me. I kept revisiting those because in them, he showed a tremendous amount of vulnerability and openness. And I don't know really even who else he may have shared some of these sentiments with. The slowness of that kind of correspondence really helped. I think when you can confront people about things, especially something like this, a man and a woman talking about misogyny, it can get really bad. But in the writing of the letters, sometimes I would take a couple of days to even respond to him. I just would sit with what he had said.

I feel very fortunate that I was able to be privy to that because it's not often that we see people do that right in this world. Just confront their own flaws, like the deepest held ones and admit to regret and say sorry. I don't know. I don't encounter that a lot in my life.

Why did you want to take on this project? You have obviously all of these barriers you have to overcome. Why did you push through?

When I agreed to it, I really had no idea what I was taking on. I didn't realize that when you start something like this, start listening to a person who doesn't have a lot of contact with the outside world, who's really got their back up against the wall, who's constantly searching for any little sliver of hope to get out of a torturous situation, that you can't step into it and then easily step out.

I was very interested in his life. I had become very interested and committed to understanding the history of the United States because I was starting to see myself live here and be here and make a home for myself here. I felt very strongly instinctively that this was a story that needed to be told. But I didn't know really what I was taking on until even yesterday was pub day, and I just was alone. And I just sat down and cried because it's been so much of my life. It's been so many, many years, and so much work and labor and not always supported, on any side of it.

I think another reason I took it on was because my life has been very much shaped by the fact that my uncle, who was a journalist, a playwright, an actor, was assassinated during one of the country's insurgencies. There was a so-called Marxist insurgency against the government, and 60,000 people were abducted and killed. My uncle was one of them. He was taken from his home, he was killed, his body was dumped in the ocean. And that really changed and affected my whole family. There was always a sense of sometimes when you tell the truth, when you speak to power, these are the consequences and it's unjust, but it's just the raw brutality of the world. So in my family, there is a bit of this sense of righteousness, like when someone is wrongfully being punished and tortured, as I feel Maroon has in his life, that you should do something about it if you can

Now that the book is finished and out in the world, and Maroon is no longer with us, has your perspective on his story changed at all?

I don't think so. I hope always that the book doesn't remain a stagnant thing. Because for me, every time I read it, at every different life phase at which I revisit this book, I take something different from it. I took one thing from it when just out of undergrad, and then when I was a working person, when I was pregnant. I've revisited it a lot as a mother, and as my child has grown, and it's changed. Every time I look at it, I take something else from it. So I hope it is an evolving book in that way. But the sort of fundamental ideas that are being expressed, I don't think they've changed.

Can you talk more about what you took from it after becoming a mother?

I never really queried Maroon a lot about himself as a father, which was strange because I really did come to this book a lot through his children. The initial draft he had sent in response to questions that his daughter, Sharon, had started asking him about his life. And it was a private family document. I don't know that they had ever intended it to be widely circulated.

After my son was born, the whole thing just took on this other hue. I'm reading these early chapters and thinking, wait, but where are the kids? What are the children doing? Who's feeding the children? Who's taking them to school? Who's doing the school runs? All these things that just don't occur to you when you're not a parent. And in fact, the man who authored the afterward of the book, Kempis "Ghani" Songster, who was incarcerated as a juvenile lifer and then his sentence was commuted, he spent a lot of time with Maroon. He was also incarcerated for many, many decades. And he came out in 2017 and had a son who is the same age as my child. So we've talked about that a lot. We've talked about what Maroon felt about himself as a father. And there is a little bit of that in the afterward, which I'm really happy about.

Have you thought about how you're gonna start telling your son about Maroon as he gets older?

Oh, he knows (laughs). We have this shrine back home where we have the statues and pictures of our deceased relatives and Maroon's been on the altar for a long time. He's a very curious little child and he's seen me through all of this. I just remember like as soon as he was born, I would nurse him and be typing, 'cause I was editing the book. I finished writing the book right before he was born, and then two weeks later I was like, OK, I need to edit this now. I think it's sort of in him. He has asked, where was he? Why was he in prison? And then he, as 5-year-olds do, sort of loses interest and wants to play with his train. But I think it'll happen very organically because this is not a little box in our lives. My husband and I have lived this for so many years of our relationship and, even in the decision to have a child and have a family, there's a lot connected with this idea, this commitment to something larger than oneself. So I think our son is just sort of in that movement.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.