August 05, 2015

Illustration/Instagram

Illustration/Instagram

What if we were motivated to run, not to improve the state of our bodies, but to improve the state of our minds?

When I was a kid, I used to sneak outside my parents’ house and dash from the corner lamppost to the Presbyterian church at the head of our dead-end street. Its stark, white steeple was something of a lightning rod to me. By the time I arrived in its concrete shadow, panting and wheezing, all electrical chaos seemed to have left the atmosphere.

Sprinting down that deserted, suburban street, in a pair of worn-out Reeboks, I outran the dinner plates my parents flung at each other, the insults classmates hurled at me about my buckteeth, my bad mushroom cut.

As an adult, I’ve outrun illness, anxiety, grief.

I run to keep pace with happiness, too, to celebrate good health, how far I’ve come. I run to examine my thoughts and ponder my dreams. I take to the streets in the sunshine, snow and pouring rain. Sometimes lightning strikes and I’m hit with a great idea.

Most people assume runners run exclusively to stay fit and lean, for the license to eat and drink whatever we please. We’ll be the first to admit staying fit and healthy is part of what makes running so great. However, for many runners, physical fitness alone is not our main priority. We’re running, instead, to tap that elusive mind-body connection, by which every footstrike dislodges a bit of psychic pain or debris. We’re running because, after so many miles, the metronomic jog becomes so profoundly soothing, it’s like falling asleep on a train.

Women, in particular, bear the brunt of this misconception about why runners run. When people see a woman they perceive to be overweight running, they assume she’s doing so to shed pounds. When people see a woman they perceive to be lean running, they assume she’s doing so to stay that way. In short, these presumptions stem from our culture’s belief that women run because they are shallow or vain; they must be in pursuit of a better body, not a better state of mind.

All this speculation about a woman’s motivation to run based on her body type leads to body shaming at both ends of the spectrum.

“What does a real runner look like?” The world demands to know. Only the most important word of this question is implied. “What does a real female runner look like?” is what we’re really asking.

Last year, Hannah McGoldrick chronicled her experience being body shamed for Runner’s World Zelle.

A recovering anorexic, McGoldrick wrote that she took up running not to burn calories or perpetuate the eating disordered mindset; instead, she began running as “therapy,” eschewing the ultra aesthetic world of ballet for a sport that demands participants literally put in what they expect to get out. For many people recovering from eating disorders, anxiety, depression, even substance abuse, running is a gateway to long-awaited peaceful stasis. And, for all the “exercise extremist” accusations non-runners like to lob at runners, those of us on the inside know the truth: Running is all about moderation.

When McGoldrick modeled one of her favorite running outfits for the launch of Zelle’s "Run Outfit of the Day" series in the fall of 2014, the Internet’s “lynch mob” responded by launching a full-scale attack on her body:

“She could use a sandwich.

We don’t want to see thin models.

Why doesn’t Runner’s World show real runners with real bodies?

This girl looks like she weighs 90 pounds.

She’s anorexic.”

What the Internet trolls didn’t bother to consider is that, in fact, because of running, McGoldrick was enjoying the best mental and physical health of her life.

“I lift weights. I cycle. I eat healthy. I get a good amount of sleep. I indulge when I want. I drink wine, eat ice cream, enjoy a good burger. When I was anorexic I couldn’t do any of that. I couldn’t run because I got palpitations. […] My muscles were so weak I could barely lift a five-pound weight. I didn’t eat. I had a very difficult time sleeping despite being tired all of the time. I never indulged. Burgers gave me panic attacks.”

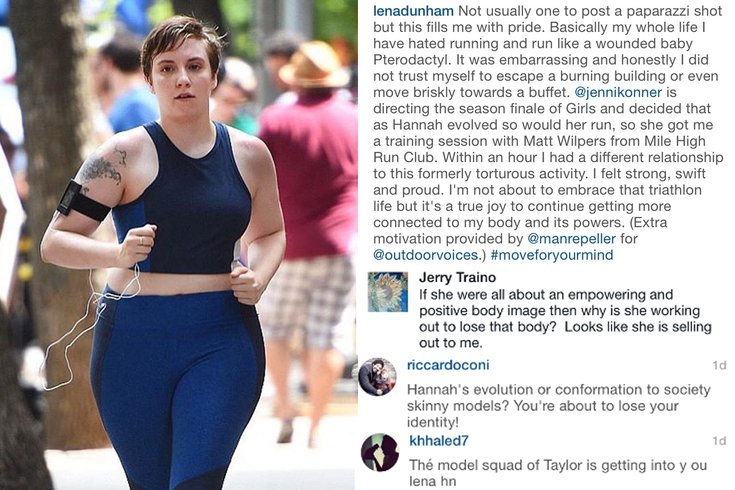

Last week, Lena Dunham Instagrammed a paparazzi candid of her running through the streets of New York City. The accompanying caption describes how she’d never been a fan of running until she started training for her character in "Girls."

Dunham explained, “as Hannah evolved so would her run.” The unrepentant feminist writer, director and actress, who has been outspoken about her battle with obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression and anxiety, went on to describe the therapeutic effect physical activity has had on her mental health:

“It has helped with my anxiety in ways I never dreamed possible. […] To those struggling with anxiety, OCD, depression: I know it's mad annoying when people tell you to exercise, and it took me about 16 medicated years to listen. I'm glad I did. It ain't about the ass, it's about the brain.”

The Internet reacted with a torrent of hostility. Its criticism largely ignored Dunham’s endorsement of the #moveforyourmind initiative, geared toward raising awareness about the positive impact physical activity has on mental health. Instead, Dunham’s detractors honed in on why she should or should not run, with regards to her body.

As someone who’s repeatedly been body shamed by silly, hateful Internet trolls, it goes without saying: I’m disgusted on Dunham’s behalf. But I’m not worried for her, or McGoldrick, or myself, or any woman who’s experienced emotional healing through running, whatever effect it’s had on her body. I do worry about potential future runners, who might be influenced by the sort of nonsense that says women should and do only exercise to influence their physical appearance. This black-and-white thinking insinuates that women who run are body-obsessed and insecure, while those who wish to promote "positive body image” shouldn’t be caught dead pounding the pavement or else risk being seen as “selling out.”

Both men and women are constantly bombarded with public health messages that say we should exercise more to enjoy better physical fitness. That message rings loud and clear because it is true.

At the same time, the pressure to change our bodies with exercise can be so paralyzing it might actually prevent some people from lacing up and getting out the door. What if we were motivated to run, not to improve the state of our bodies, but to improve the state of our minds?

If you’re someone like Dunham used to be, who desperately wants to run but is so daunted by the idea of running for fear of looking like “a wounded baby Pterodactyl,” please take her advice. Don’t think about running as a means to lose weight and burn calories. Think about running as a means to feel sane. The next time you’re feeling depressed, or anxious, or overwhelmed, throw on a pair of sneakers and sprint out the door, down the street, however far you need to go to feel like you can go on.

Forget about your body. Run for your mind. You might get hooked. You might even save your life.