A woman strutted southward on Broadway at dusk, her frizzled, brown hair covered beneath a black hood.

Dressed inconspicuously, she carried a handbag on her left arm as she turned onto a desolate Camden block, passing a shuttered corner store.

Moments earlier, the woman allegedly had approached a vehicle, offering its male driver oral sex in exchange for $20. The proposition made, she headed toward Kaighn Avenue to meet her john.

The man, an undercover police officer, never appeared at the agreed location. Instead, an unmarked police vehicle pulled up and a trio of officers arrested the woman on prostitution-related charges.

The woman was one of 15 arrested last Wednesday during a monthly prostitution sting conducted by Camden County Police. Yet, police say, these women need help, not charges.

That’s why an initiative offers prostitutes the opportunity to avoid misdemeanor charges by completing a diversionary program. But most prostitutes don’t accept the offer, police say, instead heading back to the streets to feed a drug addiction.

“Usually, more come back than we get to help,” Camden police Lt. Anthony Carmichael said. “We may get 15 girls a night. If one or two get help, that’s a lot.”

By that standard, last week’s sting marked a success. Three eligible women decided to enter the program. Another woman, burdened by multiple outstanding warrants, will need the approval of a municipal judge.

Whether they successfully complete the program is a different story.

Lt. Anthony Carmichael escorts reporters as Camden County Police conduct a prostitution sting last Wednesday. (Thom Carroll / PhillyVoice.com)

'THIS IS JUST DRUG ADDICTION'

On any given night, Carmichael said, 30 to 40 prostitutes will roam Broadway, a major corridor linking to many side streets conducive to illicit activity.

Most of the prostitutes come from the suburbs, police say, as do many of the men seeking their services. The prostitutes typically range between ages 17 and 24, but Carmichael said police once arrested a 15-year-old.

“They’re here because they’re on drugs,” said Sgt. Janell Simpson, who oversees the Special Victims Unit. “We don’t have prostitutes like Vegas-style or Atlantic City. This is just drug addiction.”

Those addictions cost money. Prostitution — which Carmichael estimated can earn the women $100-$200 a night — offers a means to those who have fallen into dire circumstances.

“To see that their life took that turn, it’s a sad thing,” Carmichael said.

Many prostitutes also turn to petty theft to support their drug habits, police say. Some are raped.

Many are arrested repeatedly, cycling between the streets and prison cells.

“These aren’t just one-time offenders,” Police Chief Scott Thomson said. “These are people that are stuck in a lifestyle that they just don’t want to be in. They are going to be back out there on the streets unless there is an intervention.”

Camden County Police transfer a woman arrested on prostitution-related charges to a holding van during a sting last Wednesday. (Thom Carroll / PhillyVoice.com)

A NEW APPROACH

Policing philosophies toward prostitution have evolved to a point where many municipalities have adopted diversionary programs in hopes of mitigating the problem.

“When you look at the cause of what’s driving the women to prostitute themselves out on the street, it invariably has to do with addictions and mental health issues,” Thomson said. “Therefore, a pair of handcuffs and a summons does very little to address the problems that are causing the situation.”

Camden police partnered with Seeds of Hope, a faith-based Camden nonprofit, about two years ago to debut their own prostitution diversionary initiative.

Following prostitution stings, police bring the women to a staging area established by Seeds of Hope. There, the women receive a meal and get an opportunity to decompress. Then, they are given a choice.

The women may choose to enter a rehabilitation program at Walter Hoving Home, an out-of-state Christian facility, but only if they do not have any outstanding warrants. The prostitution charges are dropped upon successful completion of the program, which lasts at least six months.

Yet, most women decline that opportunity, electing to face misdemeanor charges that carry maximum penalties of $1,000 and six months of probation. Others try it out, but end up back on the street.

“There have been a few occasions where girls have changed their lives and have gotten off the streets,” Thomson said. “Some have left for a while and invariably end up getting pulled back in. Others, we just can’t reach.

“That’s not going to deter us from doing it, because there are some girls who will take the help, even if it’s begrudgingly.”

Diversionary programs have appeared across the country, but they have not received universal praise.

Some have been criticized for being soft on crime or coercing women into social services by threatening jail time.

Thomson stands by Camden’s program, partly because it makes financial sense.

“It’s less of a crime issue and more of a public health issue,” Thomson said. “It costs far less to have them be engaged in a social service program than to house these folks in jail.”

Camden County Police say Broadway, pictured above, is notorious for prostitution. (Thom Carroll / PhillyVoice.com)

ANGELINA’S FALL

Angelina Jones remembers the confinement and confusion she felt the first time she prostituted herself, wondering whether she could go through with the act. But she desperately wanted to get high.

“It happens; then I’m just sitting there,” Jones said. “I got that money in my hand. That’s what kept me going back out, regardless of what you felt.”

Jones roamed the streets of Camden for more than two years, she said, trying to feed a heroin addiction. She was in and out of jail and hospitals several times. She also considered suicide.

“You get run down so quick. It was only a matter of months before I looked like I had been out there for years and years.” – Angelina Jones, former prostitute

“With that lifestyle you learn to do things that you’ve never done before,” Jones said. “You experience things that you don’t want to experience. It’s crazy, but so powerful and so destructive at the same time.”

Jones traces her path to prostitution back to her early childhood, when her father passed away. Her mother and a boyfriend began using drugs, Jones said. Soon, the family was homeless, bouncing between hotels, abandoned houses and the homes of friends.

The Division of Youth and Family Services removed Jones and her five siblings, placing them in foster care. There, Jones said, she was sexually and physically abused.

At age 17, Jones said, she was kicked out of her foster home and left to fend for herself. She began taking pills and, eventually, heroin.

“I was so desperate to get high and not feel anything,” Jones said.

She turned to prostitution on the advice of the same woman who introduced her to heroin. As a result, Jones said, she was raped and preyed upon by johns.

Jones also said a sheriff's officer, Thomas W. Smith, consistently provided her heroin and money, sometimes in exchange for sex. (Smith pleaded

guilty to hindering apprehension, avoiding charges of official misconduct.)

“You get run down so quick,” Jones said. “It was only a matter of months before I looked like I had been out there for years and years.”

But Jones has a redemption story. It began in September 2012, when she was locked up awaiting a hearing.

It involved a persistent woman who has dedicated herself to restoring the lives of women who have turned to addiction and prostitution.

'SO FULL OF SHAME AND GUILT'

Brenda Antinore never sold her body for money. But she does not doubt that she would have – if her former drug addiction had required it.

Antinore and her husband, William, were busted for crack cocaine possession in the mid-1990s. William Antinore, a prominent lawyer, was charged with embezzling federal money to fund their drug habits. He was disbarred and served time in jail.

“I didn’t have to prostitute, but I would have,” Antinore said. “We stole money from clients. When it hit the fan for us, it hit the fan for us. It was very public.”

In time, the Antinores rebuilt their family and founded Seeds of Hope.

As part of the nonprofit’s She Has A Name ministry, Brenda Antinore opens the family’s Broadway home, offering meals, showers and feminine hygiene products to the women who roam Camden’s streets.

She also provides a place where women can share their burdens while receiving encouragement and love. Her phone is always on.

“They feel so full of shame and guilt,” Antinore said. “When you peel it back for a minute … you know what you see in the mirror and you just don’t want to feel the pain of the choices that you’ve made and the things that you’ve done.”

Antinore watched as police arrested prostitutes who inevitably ended up back on the streets without getting the help they needed. Several years ago, she approached Camden police about offering the women an opportunity for help.

Thanks to the willingness of police, some women have sought that help through the diversionary program. Others, as Antinore says, are dying at her door.

“I can’t make them take help,” Antinore said. “We can set up the strategy, with this diversionary initiative, and provide this context of care and love, but the bottom line is that that person is the only one in that moment that can say, ‘Truly, I’ve had enough.’ "

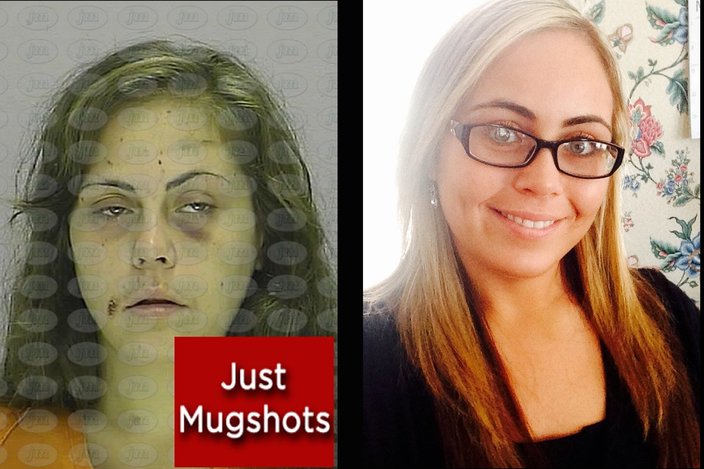

"I would never want to go back to where I was," said Angelina Jones, a former drug addict and prostitute. Her mugshot is on the left. Her image today is pictured on the right. (Contributed art)

'THAT'S NOT ME ANYMORE'

Angelina Jones said Brenda Antinore pursued her for weeks, offering to help her overcome her problems. Jones resisted.

“Once she told me that I’ve been where you’ve been,” Jones said. “All I want you to know is that this is not what you deserve. You don’t have to live like this. I just broke down in tears.”

Slowly, Jones said, she began to confide in Antinore, relishing the hugs she received even though she was bloody or dirty.

Yet, her lifestyle continued until she found herself in prison, burdened by several outstanding warrants. Antinore lobbied the judge to allow Jones to enter the Walter Hoving Home, a nonprofit shelter for women gripped by addiction, instead of facing charges.

The judge granted the request.

The 12-month program was tough, Jones said, but it transformed her life. She adopted a Christian faith and confronted the deep-rooted issues that led her to addiction and prostitution.

Examining those issues without drugs cause many to fall, Jones said. She estimated that about 50 percent of people fail to complete the program.

“The first thing that they can think about is drugs to numb that,” Jones said. “It’s not that they’re thinking that they don’t deserve a better life. Most of them are just not ready to change. You can’t force somebody to get help that doesn’t want it.”

Jones was sent to Walter Hoving Home before Camden launched its diversionary program. Her success, in fact, helped pave the way for the initiative, Antinore said, by establishing a relationship between the rehabilitation facility and Camden law enforcement.

“I can look back on my old life and say that was me, but that’s not me anymore,” Jones said. “It’s just amazing. I’m overwhelmed with gratitude with my life that I have in Christ. I wouldn’t change it for anything. I would never want to go back to where I was.”

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice