April 17, 2019

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

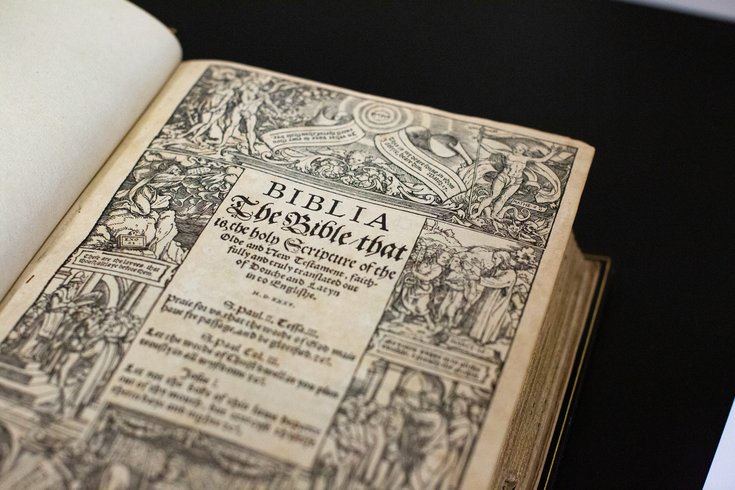

The Coverdale Bible, from 1535, is the first complete Bible, (including both the Old and New Testament), to be translated into modern English.

A family's love for a lost child has led to a remarkable collection in Philadelphia of one of the world's most widely read books: the Bible.

Susan "Kimmy" Dunleavy was killed in an auto accident in 1977. A year later, The Susan Dunleavy Collection of Biblical Literature at LaSalle University was established by her parents, Francis J. Dunleavy, President of ITT, and his wife, Albina, to honor her.

At first, the collection, house at the school's Connelly Library, was rather narrow. According to its web page, it was tasked with “documenting the history of early Bible illustration, with special emphasis on 16th century woodcut Bibles."

Bibles printed by Christoph Sauer in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia are now part of the Susan Dunleavy Collection of Biblical Literature at La Salle University. In North America, Sauer was the the first German language printer and publisher, and created the first German language Bible.

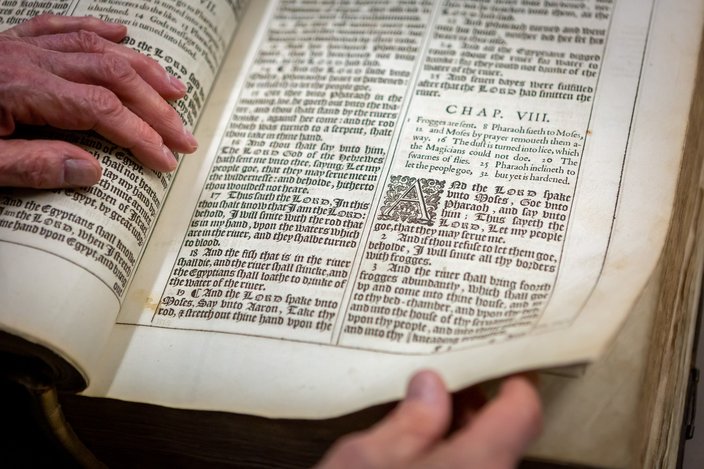

The collection has since grown to now include Bibles and other religious materials, some from as far back as the 15th century. Among the collection's treasures: two first editions of the King James Bible, first printed in 1611, as well as a second edition printed in 1613, and a Coverdale Bible, the first in English produced on a printing press in 1535.

La Salle's Coverdale is one of only a few of the first editions in the United States. The pages in the leather-bound book have not yellowed, and the black ink is still dark. Its namesake, Miles Coverdale, did the translation from Latin and German. (The Bible was obtained from an auction at Sotheby's in 1980.)

Most of the works are in English – albeit, in “olde” English.

A bequest by the Dunleavy family provides an annual income to add to the collection.

According to the university: “In addition to several of the basic illustrated Bibles of the 16th century, the collection has acquired ... first editions of the so-called “Breeches” or Geneva Bible (with which Shakespeare was so familiar), of the Rheims (1582), and Douai (1609). Among items of special interest is the Book of Psalms used by St. John Fisher (1459-1535), friend of St. Thomas More and companion with him in martyrdom under King Henry VIII.”

There are more than 200 Bibles, along with about 1,200 other religious volumes, housed in a climate-controlled environment in the Connelly Library. (The collection is open to the public but an appointment must be made by calling either 215.991.2274 or 215.951.1295.)

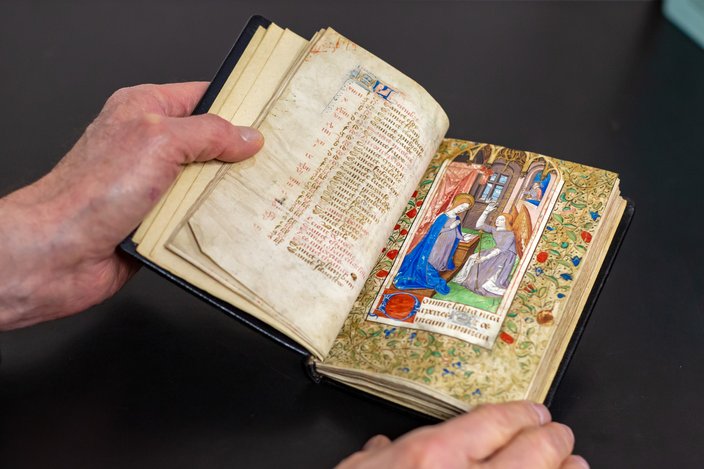

Created in Paris in 1475, this hand-written and hand-drawn Book of Hours, contains notable readings from the Bible.

It is overseen by John Baky, retired head librarian at the University who also created and curates several other collections, including one on Bob Dylan and another on “Imaginative Representations of Vietnam.”

The oldest item is an illuminated Book of Hours made in 1475. It is in Latin – which Baky said is atypical of the collection – and was handwritten by monks on vellum (animal skin) and hand illustrated using colored inks and gold leaf applied to the leaves of the manuscript by hand.

Some of the books are huge: the King James Bibles weigh 20 pounds, and have holes in them so they could be chained to lecterns to prevent theft. Other Bibles are small enough to fit in the palm of a hand, and were made for individual use.

Much of the items are several centuries old. As with any rare or “old” books, the road from printing press to today is often one of reverence and luck.

“There is some irony in the survival," said Baky. "That is to say a fair number of early printed works were not necessarily important, or even valuable, though all would have been pretty scarce and limited in number because the printing process was in its infancy, it was costly to do, and general illiteracy was extremely high.

The rare King James Bible First Edition in the Susan Dunleavy Collection of Biblical Literature at La Salle University.

“Codex books that are 400- to-500 years old had to be commissioned by either the Church, wealthy aristocrats, or the nobility. The pages for these commissioned printings were printed in sheets and then later folded and cut to look like what we know today as 'books.' Once the printer had the sheets printed, they would be sent to a binder or artisan to be bound in leather or wood or other materials. The person or institution having commissioned the pages to be printed would then pay for that binding themselves or pay the printer to have them bound.”

“The books that did survive did so often by pure serendipity and good luck over time,” he said. “But because the arc of history was so voluble and chaotic, it is the case that both individual books and entire libraries could be lost or destroyed or hidden or ignored. And since there was so much disruption over time, it would not be unusual for many unimportant books to end up surviving and many valuable ones ending up lost or destroyed or only in private hands. That's the irony of historical survival for artifacts in general.”

“The last element of survival is that books made before about 1850 or so were made of materials that simply last seemingly 'forever,'" said Baky. “Paper was made from rag pulp and inks were of a certain quality, and bindings were often extremely durable. Paper made 500 years ago often looks today like it was produced just yesterday, and so do leather and wood bindings that have been cared for or restored.

"In the end, books survive because someone cared enough to protect them, Baky said. "Pure chance in many cases. The largest, richest library in the ancient world - at Alexandria, Egypt - burned to the ground with everything in it. Those were not necessarily books as we know them , but the point is that survival depends on all kinds of historical events over which no one has control.”

The recent fire at Notre Dame just days before Easter is a reminder that history has proven kind to this gathering of tomes. And that a family created it out of love for a child

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice