June 09, 2015

Photo courtesy/Nancy Fisher

Photo courtesy/Nancy Fisher

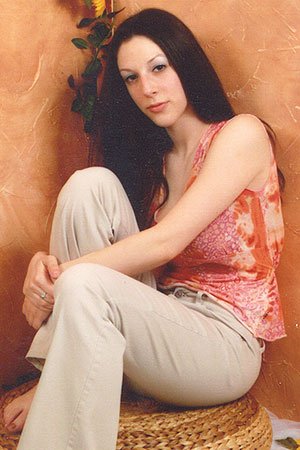

"She was very expressive, as you can tell from her writing and her words,” Nancy Fisher says of her daughter Natalie Cribari. “I like to think that she probably would have gone on and had a career in writing.”

The first time Natalie Cribari decided to try heroin, she was a cheerleader and an "A" student at Central Dauphin High School. The decision changed Natalie’s world — and that of her family — forever.

A girl described as bubbly, creative and social devolved into an addict who fed insatiable drug cravings by stealing from her family. Natalie’s addiction ultimately claimed her life, at age 20, on March 28, 2006.

But her memory and the harrowing reality of her addiction survives, in part, through a poem she penned in prison while experiencing withdrawal on Christmas Day 2005.

Titled simply "Heroin," the poem personified the drug as an abusive lover whose grip Natalie could not escape. It went viral earlier this year, potentially touching countless families affected by the drug and its powerful addiction.

“She was very expressive, as you can tell from her writing and her words,” Natalie's mother, Nancy Fisher said. “They were only some of the most powerful words that she wrote. I like to think that she probably would have gone on and had a career in writing.”

Nine years after her death, Natalie’s family reflected on the struggles of her addiction and their difficulties coping with their grief.

“So many things change and can happen because someone can get addicted,” said John Cribari, her father. “That’s the real lesson of addiction — the ripple effect and the pain, the anxiety, the stress that parents go through.

“It’s, quite frankly, probably the worst thing that you’ll ever go through as a parent — the addiction of a kid and the loss of a child on top of it.”

Cribari family members described themselves as a stereotypical suburban household.

John Cribari worked as a company executive. Fisher, then his wife, mostly stayed home, caring for their three children. They took family vacations to the beach.

“I think that’s why, in particular, our story garners a lot of interest,” Fisher said. “How could this happen to a family that is so together and does all the right things? … The bottom line is it could happen to anybody.”

Natalie became susceptible when she began hanging with what Fisher described as the “bad-boy crowd.” Natalie initially resisted the pressure to try heroin but eventually relented. Immediately, she was hooked.

Natalie hid her addiction from her parents for some time, but eventually sought their help.

“She said to me, ‘Mom, once I did it, I knew I was never going back,” Fisher recalled.

Unable to resist heroin’s cravings, Natalie checked in and out of various rehab facilities and halfway houses around the country. But the addiction controlled her.

“It was just frustrating because I felt so disconnected from her,” said Nicole Habecker, Natalie’s older sister. “She would just be gone and disappear and come back. Sometimes, I’d scold her and sometimes I’d try to reason with her.”

“People should not be ashamed of it. It’s a fact of life. People get addicted to drugs. Some people have the strength to work through that addiction and some people don’t have the strength to fight the disease.” – Nancy Fisher, Natalie Cribari's mother

Natalie stole valuables from her family, forcing them to install deadlock bolts on the bedroom doors of their Harrisburg-area home. At one point, Fisher said, Natalie cleared her ATM card, causing the family to bounce its mortgage and car payments.

One week before Christmas in 2005, Natalie stole an expensive ring from her mother and sold it to a pawnshop. Fisher decided it was time to call the police. She knew no other way to break Natalie’s habit.

“If you keep trying to help her — although your intentions are good — all that does is enable her,” Fisher said. “She promises, promises, promises that she’ll never do it again.”

Local police arrested Natalie in her bedroom the next day. Her parents watched as their daughter did a perp walk in her pajamas. Her father signed the arrest warrant.

“As a father, that pained me more than anything,” Cribari said. “But I was just trying to protect her.”

Natalie spent the next three months locked in Dauphin County Prison. Experiencing withdrawal on Christmas Day, she wrote her most well-known poem, an afflicted portrayal of heroin’s addictive realities:

"He seemed so cool, so calm, and sweet

He swept me off my virgin feet.

We fell in love, or so I thought

My soul, Almighty love, is what he sought.

He hid his identity with a comforting mask,

Only to disguise his horrid task.

With every kiss, he sucked me dry."

In early May, the Pennsylvania State Coroners Association published its 2014 Report on Overdose Statistics. The report began with Natalie's poem. When PhillyVoice.com published the poem, it went viral, seen and shared on social media more than a half million times to date.

Natalie was released from prison on March 9, 2006. She died 19 days later.

Nine years later, the pain sits latent inside Nancy Fisher, ready to flare at any moment.

Driving past Hardees, where Natalie once worked, can trigger memories. Suddenly, Fisher said, she’ll feel like the worst mother in the world.

“I’m content, but every day is a fight,” Fisher said. “Every day, there is a reminder of what is missing and what I’ll never have because she’s gone. That never goes away.”

“Every year you get a little bit better. You’ve got to stay positive. You’ve got to say that their impact in your life was not for nothing.” – John Cribari, Natalie's father

Natalie’s addiction and death fractured the Cribari family. Fisher and Cribari eventually divorced. Their adult children, Nicole and Nathaniel, now live on the West Coast, a change of scenery that Fisher said helped them cope.

“There are days when I am sad and there are days when I miss her a lot,” said Nicole Habecker, who lives in Oregon. “Then there are days when I’m so grateful I had a sister and had such a great relationship with a person.

“I’m grateful that her life wasn’t necessarily in vain," she added. "I’m honoring her by pursuing my dreams and living a healthy, happy life.”

Habecker said she struggled through the five stages of grief — denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. She coped by journaling, writing poetry and playing music. Eventually, she connected with others' similar experiences.

“Sometimes, I felt I couldn’t talk about it because no one wanted to hear or I didn’t want people to feel bad for me,” Habecker said. “I eventually stopped caring about that. I think I found more healing in talking about her and sharing my experiences with others.”

Fisher likewise worked through an array of emotions, including guilt. She has seen counselors, but, at this point, she said there’s not much more they can provide.

“In my mind, for me, I’ve gotten (as much) out of counseling that I’m ever going to get,” Fisher said. “No one is ever going to take that pain away. I’ve been told that I’m strong and that I deal with it the best as anyone possibly can.”

Fisher acknowledged that people place stigmas on addiction, but said she never felt shame — neither when Natalie was addicted nor after she died.

“People should not be ashamed of it,” Fisher said. “It’s a fact of life. People get addicted to drugs. Some people have the strength to work through that addiction and some people don’t have the strength to fight the disease.”

Several years ago, she and her then-husband testified before a state House subcommittee, raising concerns about the insurance policies regarding addiction and the practices of rehab facilities, which permit patients ages 18 and older to check out at any time.

Natalie’s story has brought Fisher considerable attention, she said. She has offered parents of addicts a listening ear and advice, although she says there is “no master plan or magic bullet.”

Yet, Fisher called the attention a double-edged sword. She gets to share the positives of Natalie and assist others, but it also sparks painful memories.

“I realize that it’s given to me for a reason and that her words are very powerful, but it takes a great toll on me,” Fisher said. “Her dad, on the other hand, he’s better equipped to manage that. He likes the attention and he can deal with it better. He puts it to good use.”

When Natalie passed, John Cribari said he became burdened by feelings of apathy and hopelessness. He experienced shock and fought depression.

“Every year you get a little bit better,” Cribari said. “You’ve got to stay positive. You’ve got to say that their impact in your life was not for nothing.”

Over the years, Cribari constructed a website dedicated to preserving Natalie’s memory by publishing the poems she wrote. He also worked alongside state Rep. Ronald Marsico to craft drug initiatives.

But Cribari said it took him until last summer before he gained the stamina necessary to lead a substantial drug awareness effort in Natalie’s memory.

“You’re worn out by the time they become clean or pass on,” Cribari said. “You’re worn out mentally. You’re worn out physically. The addiction takes a toll on everyone around you.”

Through the Sons and Daughters of Italy Lodge 2857 in Harrisburg, where Cribari serves as recording secretary, he pulled together a team of volunteers.

The volunteers raised more than $18,000 in February for the RASE Project, a nonprofit that provides therapeutic recovery housing for women in early recovery and advocates on behalf of people battling addictions.

The volunteers, who include five families who lost children to addiction and others with children battling addiction, meet monthly. Together, they seek to raise awareness of the realities of addiction and support one another.

“We’re trying to do a multifaceted approach to this,” Cribari said. “We know there’s no silver bullet to solve this problem. We know that it’s an uphill battle, but there’s a lot of people right now who are trying to fight it. We’ll make a difference.”

For Cribari, the efforts are a way of keeping Natalie’s story and life alive. But the most rewarding aspect, he said, is the gratitude he receives from the parents he’s helped along the way.

“It’s a never-ending battle for all of us,” Cribari said. “It never stops. I wish I could write down and capsulate what a parent needs to do, what’s right and what’s wrong.”

Just days before her death, Natalie Cribari knocked on her mother’s bedroom door.

She carried a drawing that she planned to get tattooed on her body after she received her first paycheck. In flowery lettering, the drawing featured the phrase “Heaven Awaits.”

Natalie, of course, never got the tattoo. Instead, the inscription is now worn by many of her family members, including her parents and sister, who carry her memory wherever they go.