October 21, 2024

Public domain/Wikicommons

Public domain/Wikicommons

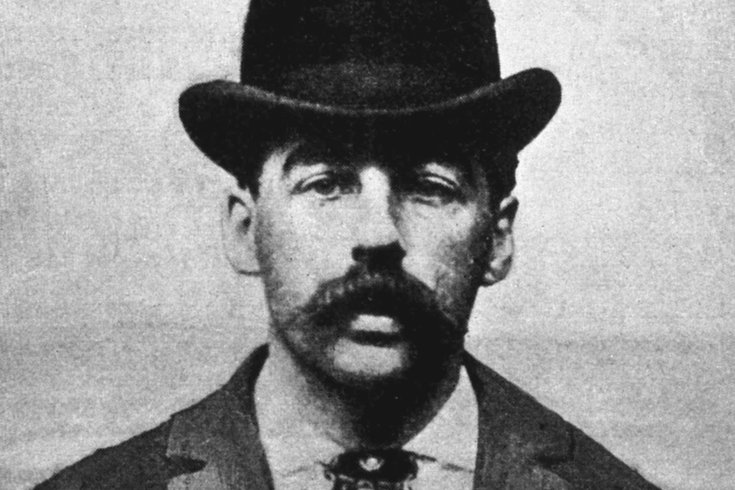

H.H. Holmes, who is consider the first serial killer in American history, claimed to have murdered 27 people but historians believe he killed nine.

None of the sensational crimes that Herman Mudgett committed in his infamous Chicago home — supposedly outfitted with gas chambers and chutes to fling bodies into the basement — sent him to the gallows on May 7, 1896. In the end, the notorious killer, better known as H.H. Holmes, was executed for the murder of a business associate in Philadelphia, whom he double-crossed in a money-making scheme.

Despite his century of notoriety, Holmes' story is difficult to decipher. The man regarded as America's first serial killer was a fabulous liar, and the journalists who told his story likely exaggerated details to sell papers. Holmes claimed he murdered 27 people, even though some of these victims were still alive when he confessed. Some estimates go as high as 200. Most historians believe he killed nine people. But he was convicted of murdering just one, a man named Benjamin Pitezel.

Holmes had conned countless creditors, employees and insurance adjusters when he and Pitezel cooked up their plot. (He also bamboozled his wives; he had three, despite never obtaining a divorce.) By this point in his criminal career, he had already abandoned his so-called "murder castle," the three-story house in Chicago's Englewood neighborhood that contributed much to his notoriety. Sources with varying degrees of credibility claim he constructed rooms where he could trap and kill his victims on the second floor, and kept torture devices and a crematorium in the cellar. Holmes had built up the "huge and ugly" residence to rent rooms to tourists visiting the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, though it's unclear if he actually killed any such guests. Most of his presumed victims were mistresses or relatives of his paramours. Pitezel was, in many ways, an anomaly.

He and Holmes planned to fake Pitezel's death and collect the life insurance money from it, splitting the earnings. They obtained a $10,000 policy from Fidelity Mutual Life Association and planned to stage the scene in Philadelphia, far away from where Holmes committed earlier crimes. He later told investigators that he had acquired a cadaver that looked enough like Pitezel, poured an accelerant on it and lit the body on fire inside a house rented in Callowhill "especially for the fraud," according to author Erik Larsen. It was supposed to look like an accidental explosion. After identifying the body, Holmes would file a claim with Fidelity.

The situation worsened when the coroner requested that someone from Pietzel's family also confirm the body was his. Alice, his 15-year-old daughter, arrived in Philadelphia in her ill mother Carrie's place. After she identified the body and Fidelity paid out the policy, Holmes took her under his care — and somehow persuaded Carrie to send two more of her children, Nellie and Howard, to join them on the road. Now wanted for numerous offenses, including fraud and horse theft, Holmes was constantly moving locations.

Private detectives eventually caught up to Holmes in Boston, but the kids weren't with him. So the Philadelphia police assigned one of their top detectives, Frank Geyer, to find them. Retracing Holmes' steps, he eventually found their bodies in Toronto and Irvington, Indiana, during the summer of 1895. A Philadelphia grand jury indicted Holmes for the murder of Pitezel just weeks later.

From his cell in Moyamensing Prison — the former correctional facility on 11th Street and East Passyunk Avenue, where an Acme now stands — Holmes wrote a memoir professing his innocence.

"For months I have been vilified by the public press, held up to the world as the most atrocious criminal of the age, directly and indirectly accused of murder of at least a score of victims, many of whom have been my closest personal friends," he wrote. "... My sole object in this publication is to vindicate my name from the horrible aspersions cast upon it, and to appeal to the fair-minded American public for a suspension of judgement, and for that free and fair trial which is the birthright of every American citizen."

The public and his jury of peers were not moved. Holmes was found guilty. Before he was hanged at Moyamensing Prison, he confessed to the murders of Pitezel and his children, as well as many others. (Historians tend to regard all of Holmes' statements with skepticism; Larson sums up this confession as "a mixture of truth and falsehood.")

Holmes' story continued long after his execution. Theories circulated that he had escaped death and even continued his crimes abroad as Jack the Ripper. Holmes' great-great-grandson Jeff Mudgett and the History Channel took on the case in 2017, enlisting help from archeologists at the University of Pennsylvania. A team led by Samantha Cox and Janet Monge exhumed his coffin from a Yeadon cemetery, concluding that the skeleton they uncovered was related to the Mudgett family.

This vague ending seems fitting for a true horror story that has been wildly obscured by the whims of its tellers and the perpetrator himself. We may never know what Holmes really did in Philadelphia — or Chicago, or Indiana, or Toronto, or anywhere — all those years ago, but we'll probably never stopping talking about him.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.