February 16, 2018

Courtesy Paul Palmer/for PhillyVoice

Courtesy Paul Palmer/for PhillyVoice

Paul Palmer spent a dozen years as an assistant football coach at Haddon Heights High School.

Paul Palmer won't be alone when he walks to the podium at the College Football Hall of Fame awards dinner in December. Two women will be by his side, though you won't see either.

That image has been on his mind since being informed of that last month. As a running back at Temple University in the mid-80's, he produced 6,613 all-purpose yards, 4,895 rushing yards and 39 touchdowns. Leading the country in rushing as a senior in 1986 (349 yards, 3 TDs vs. East Carolina), Palmer rushed for 1,866 yards and scored 15 touchdowns. He was second in the Heisman Trophy voting that year, behind Miami quarterback Vinny Testaverde.

Palmer, 53, played just a few years in the NFL. Though he did have his moments, his football legacy will forever remain in Philadelphia.

"I was just bad. Every now and then I'll bump into someone and they'll say, 'Oh, I remember when we were in elementary school…' And I'm like, 'Oh, boy. Do I have to apologize to you?' I acted like an idiot.''

As Sam Cooke sang some 50 years ago, it's been a long time comin'. The journey, however, has not been as smooth as a flowing river. But the years have left him humble and blessed.

His great-grandmother, Frances Palmer, who raised him from the time he could walk, died the day he was selected in the first round of the NFL draft. He was with her in the hospital when she passed. Nearly five years ago, his daughter Moet died from a drug addiction. He nicknamed her BIG. She was a graduate of Temple and Homecoming Queen at Haddon Heights High School in South Jersey.

That is where Palmer spends much of his time now, having been an assistant football coach for a dozen years and working with special ed. students at the high school. Quite ironic, given his past.

Growing up in Maryland, Palmer was in and out of trouble in grade school. He got into fights, he cursed, got suspended from school. He was even expelled from the school cafeteria. "I'd walk home, make my peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, eat quickly and walk the mile back to school.

"I was just bad,'' he said recently, sitting on a cafeteria chair in a hallway at the high school. "Every now and then I'll bump into someone and they'll say, 'Oh, I remember when we were in elementary school…' And I'm like, 'Oh, boy. Do I have to apologize to you?' I acted like an idiot.''

So much so that in eighth grade he was given a choice. Either be assigned to special ed. or go to another school and repeat the grade. "I knew I didn't need special ed. I was just acting out. I figured a new school, I could start over and act like I had some sense.''

Football made sense. Even though he came out of high school at 5-foot-9, 165 pounds, he loved the game from the start.

"I'm a momma's boy,'' said Palmer, nicknamed Boo Boo as a little guy, "but I never allowed myself to be treated like a momma's boy. She loved me; she loved me up. And I'm the same way with my kids. I love 'em to death but I don't baby them. I wouldn't allow her to baby me.''

And so he would play tackle football (no pads) against the older kids. They would stuff the ball in his gut, block for him, but eventually, bigger kids would knock him down and bring up the tears. "I got my toughness from neighborhood ball, not organized,'' Palmer said.

"Thank God I had older guys around the neighborhood and a couple of uncles who were really good men that I wanted to be like. One uncle, he was handsome, he could dance, play basketball, he wrestled, played football, the girls liked him. I just wanted to be like my Uncle Brian,'' Palmer said. "In the neighborhood, there were guys who looked out for me; kind of took me under their wing. I lived in a pretty close-knit neighborhood, and I had coaches who were available to my grandmother when I got out of line. So if I got out of line I knew I'd be hearing from my uncles over the weekend.''

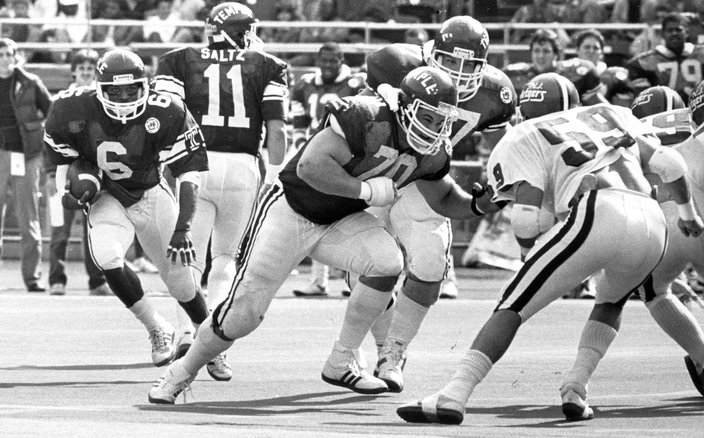

Paul Palmer (6) finished second to Vinny Testaverde in the 1986 Heisman Trophy voting.

He has heard from countless people this month, and the buzz has not yet stopped.

"It's been busy. Really busy,'' he said, noise coming from around the corner during a JV basketball game. "A couple of people have contacted me about signing autographs, and a friend has me giving a motivational talk to a department at his company. But social media has been crazy. It took me quite a few days to try and respond to people. My phone was filled up, which had never happened. It's been kind of crazy but cool.

"The kids know, people around town know. Some teachers I don't know have been very nice, and some kids I don't know really well. They announced it here at school. Around town, people are saying, 'I saw you on TV!' It's been fun. Exciting.''

And emotional.

Close friend and former teammate Joe Greenwood received one of the first calls Palmer made. They have been through weddings, funerals, births, and rarely a day goes by they don't talk to each other. "We've been like brothers since we met in '83,'' Greenwood said from his cell phone. "I honestly cried when he called, man. I knew how much he deserved to be in. Numbers don't lie. We all were emotional about it.''

Bruce Arians, their coach at Temple, said he was, "Really proud of the man he is, the father he is, the husband, the way he takes care of the high school kids.

"He had a lot of talent in a small package,'' added Arians, the only coach to offer Palmer a scholarship. "He had a lot of desire. He was someone looking for a chance, an opportunity to prove to himself that he wasn't too small. ''

Arians, who recently retired as head coach of the Arizona Cardinals and coached in the NFL more than 20 years, has called Palmer, pound for pound, the best football player he's ever coached.

"Oh gosh, he ran the ball 30-40 times a game, led the nation in scoring and was going against the top ten defenses every week like Pitt, Penn State, Syracuse, and BYU was No. 1. He always played with great enthusiasm and was someone you could truly count on all the time.''

Despite his parents not living together - his mom married and moved to Massachusetts - they tried to communicate with him as much as possible.

"My mom was a little wild, but I always knew she loved me. She made frequent phone calls; cards on special occasions. She still writes some of the nicest and most incredible things to me. She should write for Hallmark. My dad, he wasn't into sports; more into cars like the candy apple red '64 Impala he owned. He'd come to games and watch, even though he wasn't into that. I love both dearly and I've never had a problem with either one. And I never will. I grew up surrounded by love, including from both of them.''

He tries to pass that love onto the young people in his life now. Even some of the students affectionately refer to him as Boo.

"Working at the high school gives me the opportunity to be around kids, to be close to kids. I love it. It's been funny,'' Palmer said. "There have been a lot of young men we've coached that really don't have father figures around. I always tell them, 'If you need anything, ask me. If I can't get it for you I'll try and find somebody who can.'''

This past year, the NCAA determined that Palmer's work as a radio analyst for Temple football was a conflict with his coaching position at Haddon Heights. He was told to choose. He is still on the radio, but he remains a mentor.

"My (great) grandmother always told me to treat people the way you want to be treated. I always try and do that. You never know,'' he said, "what's going on in peoples' lives.''

Like his own. Like with his daughter. She was the oldest of his five children, the youngest now nine.

"It's tough,'' he said about living with her death. "It's tough. I have good days and bad days. There are certain times I'll listen to a song in the car and it doesn't affect me one bit. Next time I listen and I start cryin'. Sometimes it hits me like a ton of bricks.''

He shares her story at speaking engagements, mostly high schools. The silver bracelet on his right wrist is inscribed in part with words she had previously written, "I will always be a daddy's girl. Love you again - BIG."

She will be with him in December, her on one side and great-grandma on the other.

"There will be thousands of people behind me. People who coached me, people all the way back to midget football; my high school friends and teammates, my college teammates. I'll be propped up by a lot of people,'' Palmer said. "When I receive this award, I hope people know that I don't think for one second that I did this by myself.''

Courtesy Temple Athletics/for PhillyVoice

Courtesy Temple Athletics/for PhillyVoice