April 01, 2015

Source/eBay

Source/eBay

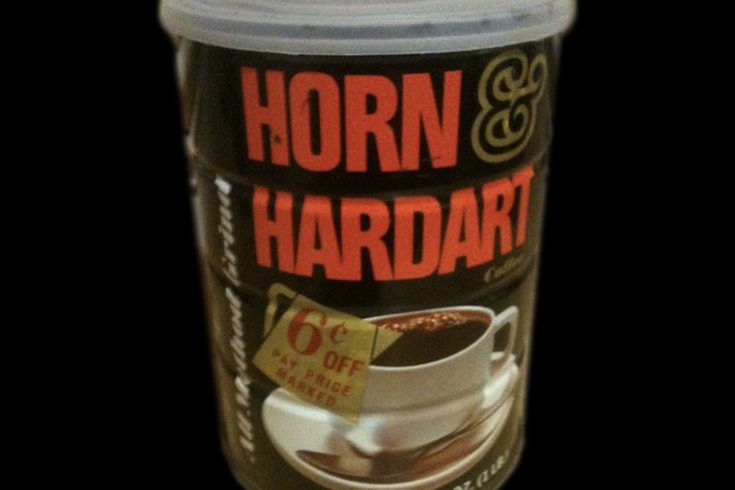

An old Horn & Hardart coffee can, like the one pictured here, plays a curious role in Philadelphia elections.

There are many factors - qualifications, experience and positions on the issues, among them - why a candidate running for public office in Philadelphia might win or lose, but don't discount the coffee can.

Ballot order can play a significant role in elections, with candidates at the top of the ballot able to draw more votes, according to some experts.

In Philadelphia, determination of ballot order for a given race is random – candidates pick numbered balls out of a coffee can – but that doesn’t make it fair to those unlucky enough to end up at the bottom of the slate, according to David Thornburgh, president and chief executive officer of the Committee of Seventy, a political watchdog group in the city.

“If [voters] feel conflicted … the order of the names on the ballot can be just enough of a subtle shove.” – Jon Krosnick, Stanford University professor

“There is no excuse for ballot position to matter, and it does matter,” Thornburgh said. “Given the advances in technology, it is not hard to have a voting machine that randomizes the positions on the ballot as every voter walks in the door.”

Thornburg wants city election officials to kick the can.

Last fall, the city started looking into spending millions on new voting machines that might be in place by 2017. Thornburgh wants the machines to be able to randomize the order of the candidates when a voter enters the booth, eliminating any advantage due to a static ballot position.

Such a change, however, would be complicated, costly and maybe even against the law, according to Tim Dowling, the city’s Acting Supervisor of Elections.

“It would be a nightmare,” he said.

The advantage to certain candidates under the current system in Philadelphia “is not trivial,” according to Stanford University Professor Jon Krosnick.

“If [voters] feel conflicted… the order of the names on the ballot can be just enough of a subtle shove,” he said.

This is especially true in primaries, where the usual trigger that helps voters make a decision - party affiliation - is absent. Voters, therefore, look more closely for other cues, including which name appears first. The impact is exaggerated in low profile races, Krosnick said.

A race between many candidates who are not well-known, like the Democratic City Council at-large race, for example, with four times the number of candidates than open seats, are susceptible to this ballot position influence. Judicial races, too.

Albert Dandridge, chancellor of the Philadelphia Bar Association, has seen the effect of ballot position. His organization tries to help voters pick among dozens of judicial candidates on Election Day by providing an online guide of recommendations.

“We recognize ballot position does have an effect because some people tend to vote for whatever the first positions are,” said Dandridge, adding the impact is visible once the ballot positions are selected and then “you have a significant number of people who withdraw from the race.”

Other candidates claim the advantage can be overstated.

W. Wilson Goode Jr., a Democratic at-large member of city council, for one.

“I picked the last ballot position [four] years ago, so clearly it's not fatal,” he said. He will have the same, last position on the May 19 primary ballot.

Nick Custodio, the campaign manager for incumbent city councilman Ed Neilson, an at-large Democrat, said the real way candidates win races is through a competent organization and good fundraising.

“People have won at all ballot positions,” he said. Neilson is fourth from the bottom on the ballot.

Municipal elections, which historically have a low turnout, can be decided by thin margins. In 2011, for example, Sherrie Cohen, a Democratic candidate for a city council at-large seat, just missed winning a spot on the general election ballot, which likely would have led to her winning office. She missed her party’s nomination by just 1,754 votes, or a fraction of a percentage point. Her name was fifth on the ballot in a year when all of the incumbents were reelected.

Moving away from the can to a new system would be costly and problematic, Dowling said. First, randomized ballots are technically against state law, he said, because the rules say that all of the ballots in a district have to be alike.

Other rules regulating how the ballot is structured, such as the requirement that a sample ballot be posted outside the precinct, would complicate any effort to implement a new system, Dowling said.

With a randomized system, “the paper costs would go through the roof,” Dowling said, because a sample ballot would have to be printed for each possible ballot.

“It’s a logistical nightmare,” he added. “There would have to be a top-to-bottom, complete change of the election code.”

Ohio has an alternative method meant to mitigate the advantage of a top spot on the ballot. In that state, each precinct has its own ballot order.

“This is done to ensure every candidate’s name appears at the top of the ballot,” said Matt McClellan, a spokesperson for the Ohio Secretary of State’s office.

Dowling says that method has its problems. There are almost 1,700 voting precincts in Philadelphia, all of which would require a separate ballot, he said, adding that each one would have to be done in both English and Spanish.

Moreover, Dowling said, voters use sample ballots to remember which spot they should select come Election Day.

“Our voters are used to voting a certain way,” he said. If “there is no set ballot, how are we going to advertise that?”

Thornburgh, however, doesn’t believe these obstacles are insurmountable.

“I think the cost of a fixed ballot position – because it so influences the race – is a really serious consideration that will outweigh a lot of other factors,” he said. “I would put that at the top of my list."