April 05, 2016

Photo courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet.

Photo courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet.

Kiwi is a rescued parrot undergoing treatment for feather destructive behavior.

What diseases do bulldogs and humans have in common? Can cardiologists help veterinarians treat gorillas with heart disease? Will a bone cancer vaccine that works in dogs help children too?

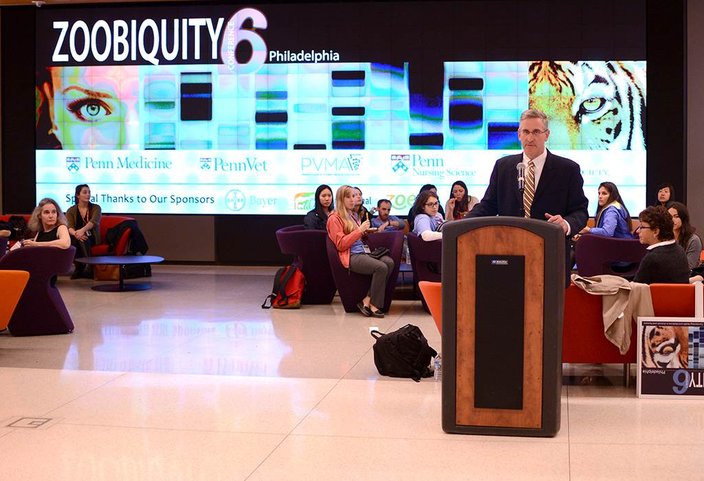

More than 200 healthcare professionals and students explored these types of overlap between animal and human health at Saturday's Zoobiquity 6 Conference, an all-day symposium that featured case studies of patients and their furry or feathered analogues. The event highlights the spirit of the One Health Initiative, which aims to bridge the gap between human and veterinary medicine by fostering collaboration between two groups that rarely interact.

"A liver is a liver is a liver, you know?” said keynote speaker Stephanie Murphy, director of the Division of Comparative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health. “It only has so many ways to respond whether it's in a mouse, or it's in a dog, or it's in a human."

Murphy, who received both her V.M.D. and Ph.D. from Penn, kicked off the conference by emphasizing how opening up the discussion between physicians and veterinarians could help find new drugs and treatments. New perspectives and approaches brought to the table by these ordinarily disparate fields has the potential to create new mutually beneficial relationships, she said.

This event was co-sponsored by University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine, Penn Medicine, and the Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association. The morning talks and case studies took place at the Smilow Center for Translational Research.

Russell Redding, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, gives final remarks at the reception.

Attendees then split up into three groups for afternoon rounds that compared specific animal cases to human patients. One went to Penn Vet's Hill Pavilion to learn about small animals, including a dog with cleft palate and an African grey parrot suffering from chronic feather-plucking disorder. The second visited Penn Vet's New Bolton Center, a hospital for farm animals such as horses and pigs located in Chester County. And the last group had a chance to see the inner workings of the Philadelphia Zoo to hear from veterinarians treating caring cardiac disease in gorillas and intestinal inflammation in a lemur.

One pair of researchers – a veterinarian and a physician, both from Penn – described their collaborative work in both bulldogs and humans on sleep apnea, a serious disorder characterized by intermittent breathing during sleep. It can prevent a good night's rest as the body abruptly and repeatedly wakes up in a struggle for oxygen, causing daytime drowsiness and straining the cardiovascular system.

"The critical part in all of this is that, working as a team, we really can find therapies that are reliable and safe for both species, and probably a few others as well," said Sigrid Veasey, a sleep apnea researcher and professor at the Perelman School of Medicine. She teamed up with Joan Hendricks, the Gilbert S. Kahn Dean at Penn Vet, to see what sorts of insights for human patients they could gain from studying bulldogs, a breed commonly prone to sleep apnea.

The bulldog is best known and loved for its sturdy build, wrinkly skin and adorably short face. Certain traits like these have been favored in breeding over many generations to up the cuteness factor, but the result of such extreme genetic manipulation is a whole host of health problems for the poor pups.

Their wrinkles and folds are susceptible to inflammation and infection if not cleaned daily. Hip dysplasia plagues many bulldogs who because of their odd body proportions, lack the ability to swim, run, or jump very far. For the same reason, even natural mating becomes an issue – thus, breeders tend to use artificial insemination. Their flat faces, short noses and excessive skin can also cause respiratory issues, such as snoring and sleep apnea.

Zoobiquity 6 tour participants visited the Penn Vet's New Bolton Center in Chester County where they listened to a horse's heartbeat.

"Bulldogs, in general, have trouble breeding and breathing – those are sort of fundamental functions, you'd think," said Hendricks.

Sleep studies they performed on different breeds of dogs using electroencephalogram (EEG) and a blood oxygen monitor confirmed that sleep apnea was a bulldog-specific issue, with pauses in breathing sometimes up to a minute long. They all snored and experienced constant drops in blood oxygen saturation, which is similar to results from human experiments.

In humans, the natural loss in muscle tone during sleep leads to an obstruction of the upper airway, especially in obese individuals. Hendricks and Veasey have looked at one drug combination – trazodone and L-tryptophan – that has effectively reduced apneas in bulldogs and is now showing promise in people.

“We know that obstructive sleep apnea is only present in sleep, and because everybody is breathing perfectly well during wakefulness, there should be some change in neurochemical drive to the upper airway,” said Veasey. “We should be able to figure this out.”

Another pair of collaborators – Tim Georoff, associate veterinarian at the Philadelphia Zoo, and Gregg Pressman, cardiologist at Einstein Medical Center – spoke to the attendees about their research on cardiovascular disease in gorillas. Specifically, the two focused on cardiomyopathy, or disease of the heart muscle, which weakens the organ over time.

“Back in the 1990s, we started noticing in and among zoos that cardiac disease was a really major cause of mortality in captive gorillas,” said Georoff. “Many of the diseases and pathologies that are seen in gorillas were the same processes also seen in humans.”

The main barrier to understanding cardiomyopathy in gorillas is the lack of sufficient data to get a better grasp of the disease processes and potential treatments. The animals have to be put to sleep in order to take cardiac measurements, but often anesthetic drugs can have an effect on heart function themselves. But at the same time, trying to perform medical tests on an awake gorilla would prove far too risky.

“Although many of our gorillas are sweethearts, they're potentially extremely dangerous,” Georoff said. “Imagine the strongest NFL football player you could ever imagine would just be beaten to death and have his arms ripped off if this gorilla really wanted to – he's that strong.”

The zoo currently houses five gorillas and takes part in the Great Ape Heart Project, which aims to fill those gaps in cardiac data. This collaborative effort of more than 70 zoos pools together cardiac exams and other medical information from gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees and bonobos in a large, singular database.

Photos courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet

Photos courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet Photos courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet.

Photos courtesy/John Donges/Louisa Shepard/Penn Vet.