May 18, 2017

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer

Dee Weitzer, center, was the lone biological male in a set of triplets at birth, but felt early in life that she was female. In 2013, she started surgical steps to transition.

Dee Weitzer, a 26-year-old medical school graduate-to-be, vividly remembers the moment she first realized how cruel the world can be.

It happened, of all places, at an elementary school parade in North Jersey. Back then, she was still known as Daniel, the lone male in a set of triplets.

To classmates, teachers and parents, Daniel was a "he." To Daniel, something deep down inside told him that wasn’t exactly right.

“I was wearing a princess outfit. It was pink, flaring out at the bottom with flowers on it. It was pretty girly,” Weitzer recalled of that parade. “That’s what set the bullying off. It was difficult to make friends. The bullying left me in a state of total confusion and sadness.

“Kids would say, ‘Daniel, why don’t you go wear a princess dress?’ They thought I was a ‘gay guy.’ It was like that through elementary, middle and early high school. There were times that I thought that maybe I couldn’t handle it. I knew I crossed a gender line and I couldn’t go back.”

As it turns out, Weitzer could handle it.

On Friday, she will graduate from the Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences.

Then, she’ll return east for a residency at a South Jersey hospital with plans to live in Philadelphia.

When she does that, Weitzer not only hopes to go on the first date in her life, but aims to tell her life story to help inspire others struggling with the gender identity issues that defined hers.

For Weitzer, gender issues surfaced even before that parade.

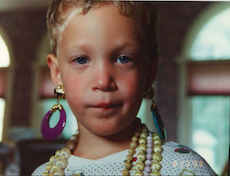

As three-year-old Daniel, earrings were a preferred fashion accessory that drew parental attention.

“My mom wanted to let me be a free spirit. My dad thought ‘this was a phase, let’s condition him as a boy’ but nothing was really done,” Weitzer recalled during an interview with PhillyVoice while visiting Center City last week.

As a young boy, Dee Weitzer (then, Daniel) knew he felt more female than male.

When Weitzer was seven, a psychologist offered a diagnosis of gender identity disorder. It felt like an accurate assessment.

During high school, Daniel would wear clear nail polish. Despite a desire to date, it wasn’t meant to be.

“I was forced to live in that role as a guy. Men would get mad at me for having a crush on them. It was dangerous to get crushes. People constantly hate you,” Weitzer recalled. "My sisters started to date people, yet I was always waiting and observing on the outside watching everyone's life move forward.

"I always stayed in the same role as an observer asking, 'When will it be my turn to date? When will it be my turn to feel like the beautiful woman I want to be? When will I be happy?' I have struggled with answering these questions for years."

College brought both struggle and clarity.

“As an undergrad at Gettysburg (College), I lost it. I got kicked out of frat houses. People would call me a drag queen. It was really bad," she recalled. “A good friend of mine’s brother is transgender female to male. I thought she looked great, so passable that you’d never know.”

It was then and there that Weitzer fully accepted her space in the world. Sure, she lost some religious friends “immediately,” but others stuck with her. Burying herself in academics became a coping mechanism.

When it came time to apply to medical schools, another challenge arose.

“It was the right time to start my life as a woman. No one there knew my past. Nobody knew my previous life." – Dee Weitzer

Though she formally changed her name from Daniel to Danielle to Dierdre – and, later, to the current Dee – she couldn’t apply as female since “they’ll know I’m a guy.”

She knew two things: She couldn’t “walk around with an ID that says ‘Daniel’” and “they couldn’t kick me out” on gender-identification lines after she was accepted to the Missouri school.

“It was the right time to start my life as a woman,” Weitzer said. “No one there knew my past. Nobody knew my previous life. I left photos on Facebook, though, so everybody found out early. I was the target for rumors at first but now, there are no problems.”

Well, almost no problems.

It was November 2013 when Dee knew she wanted sexual reassignment surgery.

“If I’m going to transition, it was all the way or nothing at all,” she said. “I’m not intermediate on anything. Go hard or go home. That’s my attitude.”

Weitzer learned much about the process attending a transgender conference. There are few plastic surgeons nationally who handle these cases almost exclusively, and she chose one of the most-renowned, most-respected in the field.

Based on positive reviews and reputation, she scheduled a first consultation within a month with Weitzer’s parents agreeing to cover the cost of surgeries “since they knew deep down inside that I could never get anywhere as a guy." Her parents wanted her to go with that surgeon because of the good online reviews.

“I’ve become a much stronger person through all this, and I’ve gotten more used to my role as a woman,” says Dee Weitzer. “I have a voice now, and I’m not afraid to use it to help people.“

"I thought that once I became the beautiful woman I always dreamed of being, then I could finally be happy and that the surgery was the bridge to get me there," she said.

On June 17, 2014, Weitzer underwent genital-reassignment surgery and breast augmentation. Then, it was time for a forehead-feminization procedure, rhinoplasty, cheek augmentation, a chin implant and tracheal shave to reduce the Adam's apple.

Three days later, she got out of the hospital.

Upon returning to school the next week, she noticed some problems – symmetry issues with the breasts and cheeks, specifically – that didn’t rectify themselves.

She didn’t reach out to the doctor until that December, though, “because I didn’t want to seem like a jerk of a patient.”

In February 2015, there was corrective surgery. Within four months, she said she experienced a "functional, soft-tissue defect" on her forehead and breathing issues because of the rhinoplasty.

Those breathing problems, brought about in part by a collapsed nostril, prompted her to decide against pursuing a career as a surgeon.

"Without surgery, I didn't think I would ever feel beautiful," she said, before questioning whether she'd have gone through with everything "if I knew what would end up happening."

On December 11, 2015, doctor and patient would see one another for the last time. The parting wasn’t amicable when Weitzer, who had deluged the doctor with emails and complaints in previous months, was told that perhaps her expectations weren’t realistic.

Of the 11 procedures performed, Weitzer said she thinks four of them met her expectations.

"If she didn’t think I was being reasonable, why did she take me on as a patient?," said Weitzer, whose nose was operated on again by another surgeon in April. "I was so embarrassed by my appearance."

On Wednesday, PhillyVoice spoke with the surgeon about Weitzer's experience. (Her name is being withheld at Weitzer's request.)

The surgeon reiterated that patients "really need to have realistic expectations" going into these sorts of procedures.

“I don’t want anything to do with Ms. Weitzer,” she initially said, noting that HIPAA laws restrict what doctors are permitted to say “while (patients) can hop on the internet and say whatever they want.”

“She is one data point out of hundreds and hundreds” of her patients, she said, defending her record of service to a marginalized community and the work she did with Weitzer, whose family "begged me" to perform the surgeries.

It was surely a setback, but one that's now part of her life story, not daily struggle.

Weitzer hopes her experience can serve as a cautionary tale for those seeking reassignment surgeries. The moral of that story? Things may not go as smoothly as you’d hope, so be ready for that possibility.

“Anybody interested in getting this type of plastic surgery needs to know that if things go wrong, you’ll be looking at a rough road,” said Weitzer, whose forehead shows the signs of muscle being removed but whose nose is back to the shape she’d hoped. “I’m still trying to correct some of the damage. Nothing with me is easy because of this.

“It’s mentally exhausting. It’s also powerful for me since I’ve been on the other side of the table. I can identify with patients more now.”

She remains “iffy” about going on the first date, even though she’d hoped the initial surgeries would help change that. Her confidence is still building, she admitted, noting that things could turn around for her when she moves to Philadelphia.

Dee Weitzer will graduate from medical school on Friday before returning east to the Philadelphia area for her residency program in South Jersey.

Though the nasal issues led her to abandon any designs on becoming a surgeon, perhaps it’s a blessing in disguise. She chose psychology instead, a field through which she can connect with people considering gender reassignment on a closer level.

“I still have that dream of being a role model for any transgender (people) nationwide, though right now, I don’t feel like an inspirational role model,” said Weitzer, noting she still hasn’t seen some members of her extended family because of her embarrassment.

“I want people to know my story, and I’m hoping it inspires them, especially because I’m a medical professional who went through four rounds of surgeries while in medical school,” she continued.

"I’ve never gone to a wedding. I’ve never danced with someone." – Dee Weitzer

On Friday, Weitzer will graduate from Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences. Her father, an attorney, will be there to support her, after their strained relationship in her youth developed into a closer bond as her life fell into place, .

Then, she’ll return to the Philadelphia area with high hopes as she starts her residency with the Kennedy Health System in South Jersey: She’ll help others, and she’ll continue helping herself.

“I identify with a lot of the patients, and their issues. Had I thought about suicide? In the darker times, yes,” she said. “There are so many things that I haven’t had time to do.

"I’ve never gone to a wedding. I’ve never danced with someone. I’ve never had the time to figure out my life and where I wanted to go. I've waited 10 years to date. I'd like to feel confident in myself so that I may be able to finally have someone to share a life with.”

Now, she will.

“I’ve become a much stronger person through all this, and I’ve gotten more used to my role as a woman,” Weitzer said. “I have a voice now, and I’m not afraid to use it to help people.

"Now, I’m very confident. I’m OK being out in public. I’m an open book. That way, people can learn, and I can raise awareness. I’m creating a good ending to a bad story.”

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer

Photo courtesy/Dee Weitzer