October 14, 2024

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

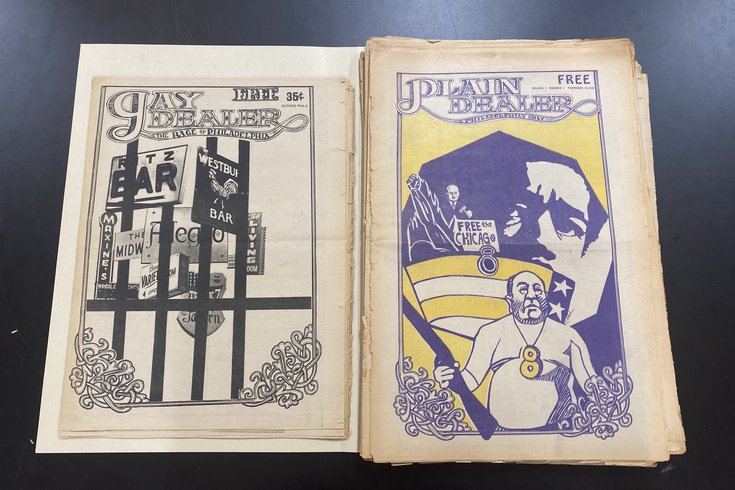

The staff of the Gay Dealer, left, spun off from the Plain Dealer, right. Both newspapers were part of Philadelphia's underground press in the 1970s.

Philadelphia's first queer newspaper lasted only a single issue, but its brief life was sensational.

Apparently funded through the sale of psychedelics, the Gay Dealer reprinted countercultural manifestos and told readers how to crochet a "gay beret." It was born out of the ashes of another underground press publication that maintained an adversarial relationship with the city's adversarial police commissioner, Frank Rizzo. An activist made sure he got a copy by hand-delivering it at the 1971 Mummers Parade.

The Gay Dealer may not have made it through the '70s, but copies of it survive at the William Way LGBT Community Center. The historic nonprofit, which opened its doors a few years after the paper's run, has preserved the black-and-white newsprint alongside other papers and publications chronicling the lives of queer Philadelphians.

"The average person, if they stumbled upon it, they might have quickly been turned off," said John Anderies, the director of the John J. Wilcox, Jr. Archives at William Way. "Or turned on."

The Gay Dealer joined a fairly robust underground press scene in Philly in 1970. Other independent, leftist newspapers included the Distant Drummer, a weekly that ran from 1967 to 1979, and the Philadelphia Free Press, which grew out of a Temple University student publication in the late '60s. The Free Press, as it was often called, attracted significant heat for its radical Marxist-Leninist views. Rizzo "vowed to destroy" the paper after an unflattering article, sending police officers to assault its writers, break into their cars and search their homes.

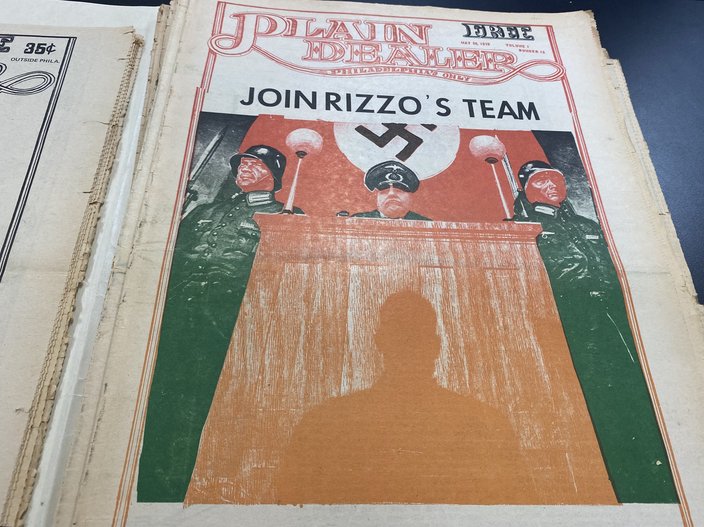

A group of staffers left the Free Press in early 1970 to form a new publication: The Plain Dealer. This free newspaper was considered slightly less radical, though it was still quite subversive. One of its writers recalled running a recipe for a bomb "that would have blown up anybody who tried to follow it." And the paper shared its predecessors' contempt for Rizzo. The cover of a May issue depicted the city's future mayor in an SS uniform, standing in front of a Nazi flag.

The Plain Dealer depicted Frank Rizzo, then the police commissioner of Philadelphia, as a Nazi leader in its May 28, 1970 issue.

The Plain Dealer struggled to stay afloat as the year wore on. Its staff and funds dwindled, and by October, it was clear the project couldn't continue. But the remaining writers decided to put out one last issue — and since all of them were queer, they decided to rebrand the newspaper.

The Plain Dealer had run some articles on LGBTQ issues during its sporadic publication. The Gay Dealer, however, would make them the main focus. To pay for this first-of-its-kind publication (at least for the city of Philadelphia), its creators turned to the illegal drug trade.

"We got gelatin capsules and we sold a psychedelic called MMDA and that's how we funded it," Kiyoshi Kuromiya, an LGBTQ rights activist affiliated with the paper, later recalled. "That was kind of an aspect of the times. ... They were purple capsules. They were kind of magenta capsules. And we filled them with a powder."

Kuromiya, a renowned organizer who marched with Martin Luther King Jr. as a Penn student and later co-founded the Gay Liberation Front in Philadelphia, was not a credited writer for the Gay Dealer. But he appears in a photo in the newspaper, smiling cheek to cheek with another man, next to a 16-point platform from the group Third World Gay Revolution. Kuromiya delivered these demands at the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia that fall.

"A lot of the Gay Dealer content is manifestos," explained Shana Cohen-Mungan, a former intern for the William Way Center who cataloged queer content in underground newspapers. "Even in the Plain Dealer, a lot of the coverage around the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention was printing the demands made by the different workshops."

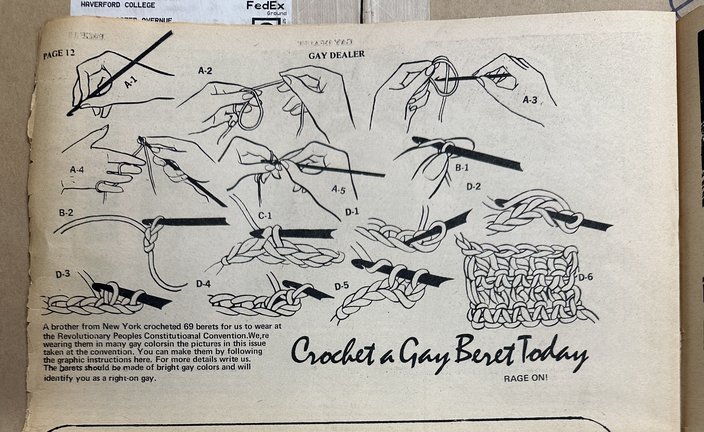

Other articles included reviews of the Mick Jagger film "Performance" and the Kate Millett book "Sexual Politics." The Gay Dealer published a cover story against gay bars as a central meeting place — young people, the paper argued, couldn't access them — and critiques of movement posters. It also dabbled in cheeky illustrations. Page 12 featured step-by-step tutorials on acting effeminately in public and crocheting "gay" berets.

"The berets should be made of bright gay colors and will identify you as a right-on gay," the instructions read.

The Gay Dealer offered an illustrated guide to crafting a “gay beret” for the People's Revolutionary Constitutional Convention.

It's unclear when exactly the Gay Dealer staff printed the paper's sole issue or how it was distributed. But by Kuromiya's account, it was shortly before the 1971 Mummers Parade on New Year's Day. There, he brought the paper's combative relationship with Rizzo — a lifelong adversary to journalists, as KYW would eventually learn — to a triumphant close.

"At the corner of Broad and Spruce, Mummer's Day Parade, we had just published it," he said later in an interview. "We distributed copies to everybody. At that time that corner had 5,000 gay people gathered there to watch the Mummer's Parade.

"I went running out into the middle of the street with a copy of Gay Dealer, handed it to Frank Rizzo, who was walking proudly down the street. And I said, 'I'd like you to have a copy of the first issue of your newest community newspaper.' And he smiled, he shook my hands, he rolled it up and stuck it in his back pocket. And everybody at the intersection shouted and applauded and made cat calls."

The Gay Dealer's death left a vacuum in local LGBTQ media. Another queer newspaper would not take its place until 1976, when the Philadelphia Gay News launched.

"The PGN sort of came to be when there were enough people with money to say we're willing to back a gay newspaper," Anderies said. "This is such a different, sort of grassroots publication.

"I don't know, I feel a little wistful about it. If only this could have been supported better somehow, what more would there might've been?"

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice Provided image/William Way LGBT Community Center

Provided image/William Way LGBT Community Center