September 21, 2016

Samuel Lang Budin/for PhillyVoice

Samuel Lang Budin/for PhillyVoice

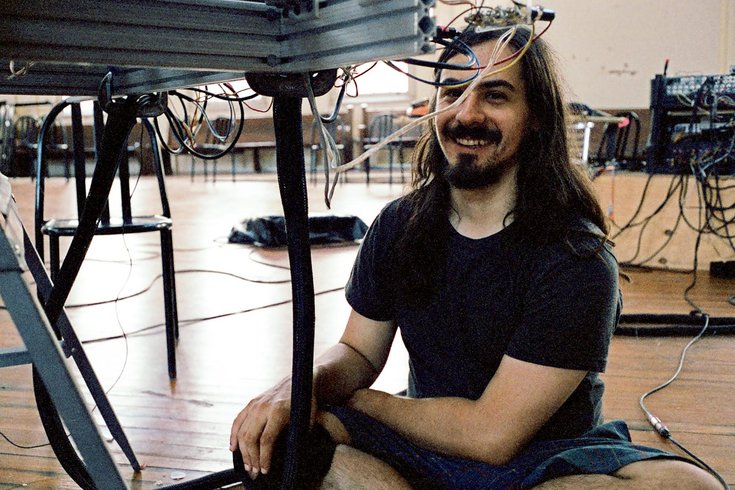

“My art practice is about listening to it, and my life practice is about not listening to it,” says Daniel Fishkin about the tinnitus he's been living with since 2008.

Every performer knows the feeling: the days and weeks leading up to an event are a harried rush of activity and problem-solving, followed immediately by a sudden crash, a stillness and silence in the wake of frenzy and nerves. That was the case for Daniel Fishkin as he presented two nights of music for his senior thesis at Bard College in 2008.

Only for Fishkin, the silence never arrived. The improviser and composer noticed a ringing in his ears following the first night’s concert that persists to this day. He has tinnitus, a perception of noise in the ears that afflicts many musicians.

“Suffers” may be the wrong word to fully capture his experience of tinnitus, however.

Since the ringing began, Fishkin has initiated a series of performances and installations under the umbrella title “Composing the Tinnitus Suites,” which create music in direct response to the altered way in which he experiences his sonic environment.

“My art practice is about listening to it, and my life practice is about not listening to it,” Fishkin explained earlier this week at the Rotunda, where Bowerbird will present four “Composing the Tinnitus Suites” concerts in the coming weeks. “This division between life and art is a big thing for me in doing this project. It’s an unresolved tension in that I don’t feel like the project stops because the tinnitus doesn’t stop. It’s the idea of living in a way where the hearing damage is driving me toward aesthetic decisions, and I think about that on an ongoing basis.”

Originally from Bala Cynwyd, Fishkin’s first musical fascination was with punk rock, followed by high school studies in jazz. In college, he began focusing on more experimental sounds and approaches, inspired by John Cage. All three influences seem to converge in his “Tinnitus Suites” and in his general approach to dealing with his hearing damage.

“Punk made it possible for me to just go into a room and do things, and jazz made it possible for me to not have a script,” he explains. “Listening to listening is something that happens in the aura of John Cage, but tinnitus is listening to the instability of your listening. I don’t need to disturb that too much, because being aware of it is actually what tinnitus gifts me, and that’s a good vantage point to have.”

If referring to a persistent, painful ringing in the ears as a “gift” seems like a bit of a stretch, in Fishkin’s explanation it’s merely a shift in perception to help ameliorate the effects of a condition he’ll likely have to deal with for the rest of his life.

“I don’t like to romanticize disability. That’s a problem that comes across in a lot of stories about ‘inspiring’ people. But I do think that I’ve had interesting perspectives on sound that directly came from the ringing, and my reaction to stimulus is girded by my aural apparatus.”

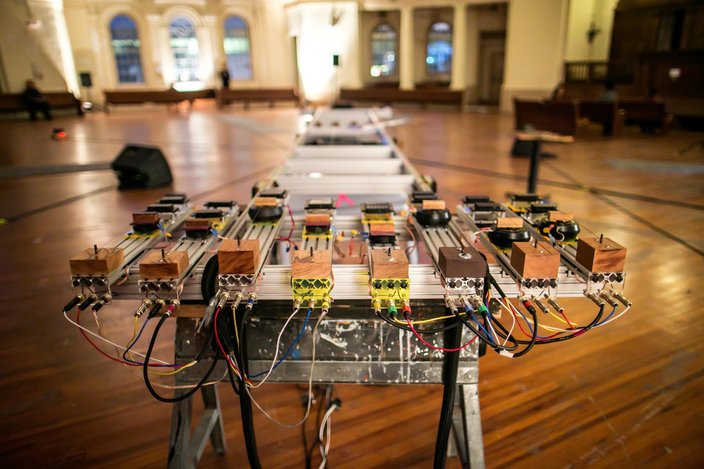

Fishkin’s “Composing the Tinnitus Suites” performances are built around the Lady’s Harp, an instrument that he invented for the project.

Fishkin’s “Composing the Tinnitus Suites” performances are built around the Lady’s Harp, an instrument that he invented for the project. The harp resembles an aluminum ladder laid on top of a row of sawhorses; amidst the scattered pews and boxes under the Rotunda’s skylight dome it could easily be mistaken for a pile of construction implements. But strung across the top are rows of 20-foot-long piano wires attached to guitar pickups and pressure transducers attached to a sound mixer. Using a variety of implements, from scraps of wood to a hammer, as scaled-up capos, Fishkin coaxes sound from the feedback of the strings.

“The danger is that someone who doesn’t listen the way that I do might just play this like a giant guitar,” says Fishkin.

As Fishkin casually drops a piece of wood onto the taut strings, the vibrations and drones suggest myriad ways in which the Lady’s Harp could be played, from the ambient to the abrasive. Its inventor is particularly strict about how it should be approached, especially in the context for which it was built.

“The danger is that someone who doesn’t listen the way that I do might just play this like a giant guitar,” he says, a palpable dread creeping into his voice. “I don’t want that to happen. I forbid that from happening. That’s not tinnitus music. You have to be willing to play the littlest thing and commit to the subtlest motion. Your job is to just find the right place and step away.”

To illustrate his point, Fishkin slowly raises the faders on his mixer, allowing an absorbing and densely layered buzz to slowly fill the cavernous room. The sound of his harp can range from the barely audible to the painfully oppressive, an experience that would be easy to mistake for the composer’s impression of his own symptoms. He’s quick to shoot down that suggestion, however, citing Franz Kafka’s famous edict that the main character of “The Metamorphosis” never be shown in illustrations of the story.

“As soon as you draw a bug, it becomes just a stupid-looking bug instead of this monster of your imagination,” he says, quickly sketching a beetle-like stick figure on the back of a piece of sheet music. “I make sure to insist, ‘No, it’s not the ringing in my ears!’ Representing it directly is kind of boring to me, but saying this is in the world of tinnitus is a little bit more apt. I think that tinnitus is a world of perception. This is the world I’m carrying around with me all the time, and I want that to be transduced for the audience.”

This hometown incarnation of “Composing the Tinnitus Suites” — Fishkin moved back to West Philly last summer – will manifest in four different performances: the first, to take place this Friday, features a newly assembled ensemble called Philadelphia Hearing Damage; the second is a duo concert with Ellen Fullman, inventor of the 80-foot Long String Instrument, an inspiration for the Lady’s Harp; Fishkin will then be joined by fiddler Cleek Schrey and bassist Ron Shalom, his collaborators in the trio New Perplexity; and the final show will feature transcriptions of early “Composing the Tinnitus Suites” performances for Ensemble Mise-En. All four concerts will be paired with conversations with neuroscientists, psychoanalysts and scholars who deal with hearing loss in their practices.

Fishkin allows that he’ll likely be in pain following the four concerts but insists that he’s judicious about choosing when to exacerbate his symptoms. “If there’s a place that I would suffer, it would be in this project.”

Fishkin allows that he’ll likely be in pain following the four concerts but insists that he’s judicious about choosing when to exacerbate his symptoms.

“If there’s a place that I would suffer, it would be in this project. It wouldn’t be OK if I went to a movie theater and the explosions from 'Captain America' are painful. That doesn’t make me feel justified.”

Ultimately, he says, the project has allowed him to re-enter a world that was cut off when the ringing started. An avid improviser, he was suddenly unable to just enter a room and start playing with other musicians without regards to the contours of the room, the sound system or the volume.

“My tinnitus threatened to sever my connection with people, and this project is the opposite. I’m trying to restore my connection with people.”

Sept. 23 & 30, Oct. 2 & 16

Admission: Free

The Rotunda

4014 Walnut St.

bowerbird.org

Ben Tran/for PhillyVoice

Ben Tran/for PhillyVoice