April 09, 2024

Provided images/Weitzman Museum

Provided images/Weitzman Museum

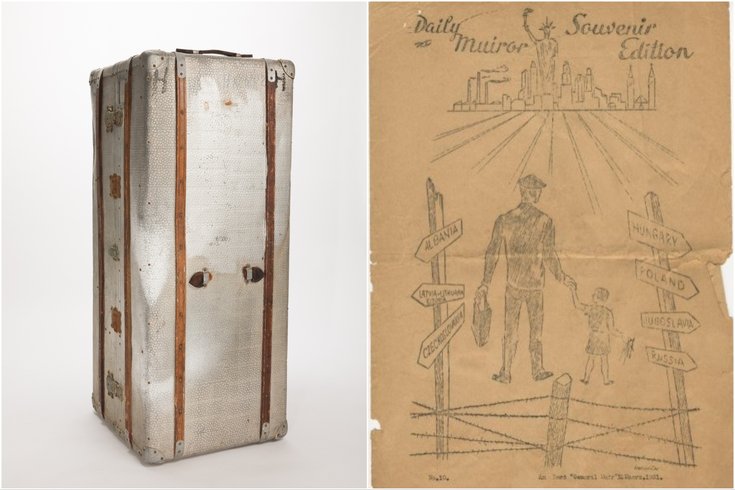

A family of Holocaust survivors left a displaced people camp in Germany for America with this steamer trunk. They traveled aboard the General Muir, which provided a newsletter (right) to refugees aboard its ship.

When Martin and Halina Hershkowitz boarded the General Muir transport ship with their 3-year-old daughter Sheila on March 3, 1951, they were ready to leave Germany behind.

The Jewish family was among those who had been stranded across Europe in the aftermath of World War II. After surviving the horrors of the Holocaust, the Hershkowitzes had ended up in a displaced persons camp in Germany, a makeshift home for survivors that U.S. officials would later conclude was little better than the concentration camps. Though the Hershkowitzes were originally from Poland, they had no interest in returning home. Instead, they secured passage to America, where they would start new lives on a chicken farm in New Jersey.

The steamer trunk that made the journey with them now belongs to the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History on Independence Mall. Established in 1976, the museum boasts the largest collection of Jewish Americana in the world with more than 30,000 pieces of art, clothing and other artifacts. It is a Smithsonian affiliate, which grants the Weitzman special access to the national museum network's resources, and if new legislation in Congress is successful, it could officially join the Smithsonian in the coming years.

The Weitzman Museum received the Hershkowitz trunk from the family's second daughter, Pearl Landesman, who was born in America along with her brother, William. In a letter enclosed with her donation, Landesman wrote that the trunk "has been an important part of our Hershkowitz family history for as long as I can remember," and it had made the family's eventual move to Florida decades after their initial immigration to America.

"Once in a while my mother would open it, and pull out some old clothes, and a fur coat she kept there in moth balls," Landesman continued. "The moth ball smell was awful, so I didn't look too closely as to what was inside the trunk."

When the family finally did go through the luggage in 2012, they discovered numerous mementos from the 1951 voyage, including a souvenir newsletter distributed to passengers of the General Muir, a U.S. naval ship that transported Jewish refugees from Germany to New York. (A descendant of a family on its 1949 voyage named her Atlanta restaurant after the vessel.) Martin and Halina had also preserved documents they received from the Displaced Persons Commission, a U.S. group created to aid in the resettlement of European refugees. The commission sprang from the Displaced Persons Act, a 1948 law that authorized the entry of hundreds of thousands displaced people into the United States — bypassing the constraining immigration quotas of the time.

The plight of refugees posed an international crisis in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Jewish survivors of the Holocaust made up a relatively small portion of the roughly 7 million people displaced by the war — 250,000, by some estimates — but given their circumstances, resettling them was a priority.

One of the biggest problems for groups like the Displaced Persons Commission was that many survivors, including the Hershkowitzes, did not want to return to their original homes. "Very few Polish or Baltic Jews wish to return to their countries," Earl G. Harrison, a Philadelphia lawyer, wrote in his 1945 report to President Harry S. Truman on the displaced persons camps. "Higher percentages of the Hungarian and Rumanian (sic) groups want to return although they hasten to add that it may only be temporarily in order to look for relatives."

Some of this wariness was due to the spreading Soviet Union. According to Pamela Nadell, a founding historian of the Weitzman Museum, those who survived the Holocaust "did not want to stay in the Soviet-occupied zone," and instead favored British or American-occupied camps.

"There's this perception that, well on the Soviet side, it's communist," explained Nadell, who is also the director of the Jewish studies program at American University. "And the Iron Curtain is descending on Eastern Europe, and they know that if they stay on that side, they're not going to be able to get out. There's of course antisemitism under the Soviet Union, serious antisemitism under Stalin.

"The other thing is when they go back to their homes, there's nothing to return to. They go back there, somebody else has moved into their apartment. Somebody else is living with the objects they had once owned. This is assuming they didn't come from a place that was completely bombed or destroyed."

Holocaust survivors liberated from Dachau were taken to a displaced persons camp in Heilbronn, Germany (pictured above). Supplies at these camps were so scarce that some still had to wear their old prison clothes.

Polish Jews like the Hershkowitzes, who lived in the village of Książ Wielki, had even more reason to move to the West. In 1946, mobs in the Polish city of Kielce killed 42 Jews and injured another 40 in a pogrom sparked by an old antisemitic conspiracy that Jews were kidnapping Christian children for ritual sacrifices. Książ Wielki is just over 40 miles south of Kielce.

"It's clear to many Jewish survivors very quickly that they need to get out of Poland," Nadell said.

For the Hershkowitzes, that meant seeking passage out of the displaced persons camps, where malnutrition was rampant and clothing scarce. (In his 1945 report, Harrison concluded, "We appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them except that we do not exterminate them.") Once the family secured a place aboard the General Muir, they spent 10 days at sea, followed by a brief stay in Washington, D.C., where the couple sponsoring them through the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society lived. HIAS was one of several agencies accredited by the Displaced Persons Commission to assist in the resettlement effort, though it was perhaps one of the best suited for the task at hand. The group, which bills itself as the world's oldest refugee agency, was formed in the late 19th century to help Russian and Eastern European Jews fleeing pogroms.

By 1952, the Hershkowitz family had settled on a chicken farm in Stockton, New Jersey. Landesman writes, "My parents worked hard to build up their egg business and raise a traditional Jewish family as best they could." Chicken farms in New Jersey were a popular destination for Jewish refugees in America who wanted to live in the countryside. According to the recent book "Speaking Yiddish to Chickens: Holocaust Survivors on South Jersey Poultry Farms," roughly 1,000 Holocaust survivors settled on farms in Vineland and other southern parts of the state.

"For these people who were really traumatized by their wartime experiences, this was a peaceful, simple, not stressful kind of way to get their footing in America," said Claire Pingel, chief registrar and associate curator for the Weitzman Museum.

After two decades in Stockton, the Herschkowitz family relocated to Florida, where the steamer trunk sat in a closet for years. It has now made one final journey to Philadelphia, adding yet another destination in the Herschkowitz's incredible immigration story — one that a surprising number of egg experts in southern New Jersey share.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Public domain/United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration

Public domain/United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration