April 10, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Trees bloom in the spring at Washington Square, March 29, 2017.

Washington Square stands as the most quaint of the five public squares designed by Philadelphia founder William Penn.

Covered by an array of canopy trees, the park serves as a popular destination for residents seeking a quiet respite or an outdoor lunch. Its landscape draws wedding photographers and even a few tourists from nearby Independence Hall.

That Washington Square maintains a more peaceful vibe than any of the other public squares is partly by design.

The square stands as a tribute to the soldiers who perished in the American Revolution. Thousands of them are buried beneath the park, as are Yellow Fever victims and many of the freed blacks and slaves who lived in colonial Philadelphia.

Because of this, Independence National Historical Park, which oversees the square's operations, only sanctions events that commemorate its past.

That story, particularly its beginning, is often a somber one.

But the square, first planned by Penn in 1682, had natural elements that seemingly would make it unrecognizable to Philadelphians today.

Washington Square sloped significantly, creating a deep gully on its eastern end. Two small streams, one known as Munday's Run, converged in the square before eventually emptying into Dock Creek. That creek, a tributary of the Delaware River, later was filled to create Dock Street after the creek became polluted.

In the 1740s, Philadelphians caught fish up to six inches in length, as well as crayfish in the streams, according to 19th century historian John Fanning Watson. There also was a pond where residents were known to shoot wild ducks.

A privet hedge once surrounded the square, making it a popular spot for young boys to cut sticks needed to construct arrows for their bows.

Grass grew abundantly in the square, and for several decades in the 1700s, the city leased Washington Square to Jacob Shoemaker and Joshua Carpenter, who each used it as a pasture for grazing animals.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceThe late afternoon sun shines on buildings surrounding Washington Square in Philadelphia, January 5, 2016.

Washington Square originally was known as Southeast Square until the city renamed it after George Washington in 1825. But long before that, the square was dubbed "Congo Square" by the city's slaves and free blacks who sought to hold onto their West African heritage.

The city's black population gathered at the square to celebrate festivals and holidays, singing and dancing to the music of their native cultures. Up to 1,000 people, both men and women, were known to take part.

"Congo Square" also served as a burial ground for the city's black population and people were known to visit the graves of their family members.

Many free blacks played a prominent role in the Yellow Fever epidemics that repeatedly swept through Philadelphia in the early 1790s, volunteering as nurses and assisting with burials. Many Yellow Fever victims were buried at Washington Square.

The Free African Society, led by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, served at the request of physician Benjamin Rush, who mistakenly believed that black people were less susceptible to contracting Yellow Fever. But within months, they too were dying at rates similar to the white population.

Jones and Allen documented their efforts in 1793, detailing their service to the city after they were accused of profiteering. An estimated 5,000 people died from Yellow Fever that year as Philadelphia suffered its most severe outbreak.

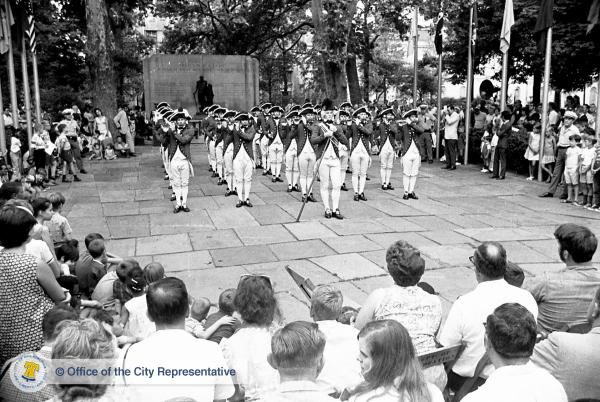

Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.orgThe Fort Meyer Fife and Drum Corps. performs at the Memorial of the Unknown Soldier of the American Revolution during Freedom Week in 1969.

Washington Square was the first of the city's public squares to be used as a potter's field, a place to bury the city's black population, poor people and criminals. This usage dates to 1706, according to Watson's "Annals of Philadelphia."

At one point, a brick enclosure of about 40 square feet was constructed at the square's center to serve as a private burial space for the Carpenter and Story families.

A cherry tree was planted at the center, under which Joseph Carpenter was buried. A woman in the Carpenter family, who died by suicide, also was interred there as her manner of death prohibited burial in a common church burial ground.

But Washington Square is best known for the mass burials of Revolutionary War soldiers and Yellow Fever victims.

During the American Revolution, large burial pits were dug along Walnut Street and filled with coffin after coffin. Many of the soldiers had died of camp diseases, like smallpox. Others had perished in nearby hospitals after suffering battle wounds.

Future President John Adams took a somber walk through the square in April 1777, observing the graves and trenches. A sexton told him that as many as 2,000 soldiers had been buried there.

"I never in my whole life was so affected with melancholy," Adams wrote in a letter. "The graves of the soldiers who have been buried in this ground from the hospital and bettering-house during the course of last summer, fall and winter, dead of the smallpox and camp diseases, are enough to make the heart of stone to melt away!"

After the British took control of the city in 1778, American prisoners of war suffered in neighboring Walnut Street prison, reportedly going days without meals and capturing rats for food. As many as 12 prisoners died daily, their bodies buried in Washington Square.

Today, a memorial featuring a statue of Washington and the remains of an unknown soldier pay tribute to those who lost their lives fighting in the American Revolution. It is unknown whether the soldier fought as part of the Continental, British or Hessian army.

The memorial, dedicated in 1957, supplanted the Washington Grays monument commemorating the Civil War. That monument now stands on Broad Street by the Union League.

After the war, Washington Square once again became a prominent burial ground as repeated Yellow Fever epidemics swept through the city. But by 1795, the square's days as a burial ground were over.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceThe Memorial of the Unknown Soldier of the American Revolution in Washington Square.

The Washington Square Planning Committee sought to pay tribute to Washington and the deceased soldiers when they sought to redesign the square in 1954.

The committee, composed of local business executives, opted for a memorial of Washington — first proposed in the early 19th century — and the tomb of the unknown soldier.

The act of digging up the remains of a soldier and reburying him did not come without its hiccups, as documented by John Cotter in "The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia."

The dig commenced in secrecy in November 1956. The laborers and archaeologist simply told curious passersby that they were doing "soil testing." They had identified three graves by the time police arrived to inquire what was happening.

The group told police that they had been hired by Washington Square Planning Committee to search for geological samples. Police sought confirmation with their headquarters and the mayor's office, but initially found no authorization of the dig.

That sent John Witthoft, the lead archaeologist, into a tizzy. A series of phone calls ensued, only ending when police received word from their chief that the dig could commence.

"We're not supposed to know what you're doing," police told the archaeologists. "Just do it."

The reasoning for the secrecy? Politics.

Witthoft was the state archaeologist in a Republican-dominated administration. Philadelphia was run by Democrats. He only agreed to the job under strict stipulations, including that the dig receive no publicity.

The dig continued with police guarding against vandalism. Five days in, the archaeologists had dug so deep their heads were no longer visible at the surface. They removed two sets of remains before discovering other remains that surely belonged to a soldier.

But another disturbance was underway.

At least one onlooker was angry that the archaeologists had disturbed "the sacred dead." A group of religious fundamentalists had decided to proselytize at the site, angering some of the other onlookers. And then the press was called, blowing Witthoft's cover.

Witthoft fled, taking cover at a friend's business before returning three hours later to see the remains safely stored in the Curtis Publishing building.

Forensic specialists later verified the sex, approximate age and a head wound possibly caused by a musket ball that had grazed the skull.

The soldier's remains were encased in a coffin and reinterred during a ceremony at the Memorial of the Unknown Soldier of the American Revolution.

Southeast Square was renamed after President George Washington in 1825.

The leader of the Continental Army needs no introduction here. But the "Father of Our Country" found himself in an unusual place on Nov. 27, 1798 — the Walnut Street Jail.

The prison, which bordered Washington Square's east side from the 1770s to 1835, housed his friend, Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a financier of the American Revolution. Unable to pay his debts, Morris had landed in jail.

Washington was there to pay his dear friend a visit.

"Back then, if you were a debtor they put you in prison, which made it impossible to pay your debts off," said Doris Fanelli, a historian at Independence National Historical Park. "You had to support yourself while you were there. He had furnishings from his home — his family brought his meals. And Washington came to see him. They were friends and that friendship didn't stop."

Washington risked his reputation by visiting his friend, whose poor land investments and gaudy mansion had made him an easy target of mockery, historian Ryan K. Smith wrote in a book on Morris.

But Washington also risked his life by walking into a prison besieged by Yellow Fever.

"Were these inmates quiet as they encountered Washington's recognizable face?" Smith writes in "Robert Morris's Folly." "Did they salute? Did they risk a hoot or a yell?"

Washington noted the visit in his diary, writing that he dined "in a family with Mr. Morris," but did not elaborate on their discussions.

Morris was released from prison in 1801. He died five years later.

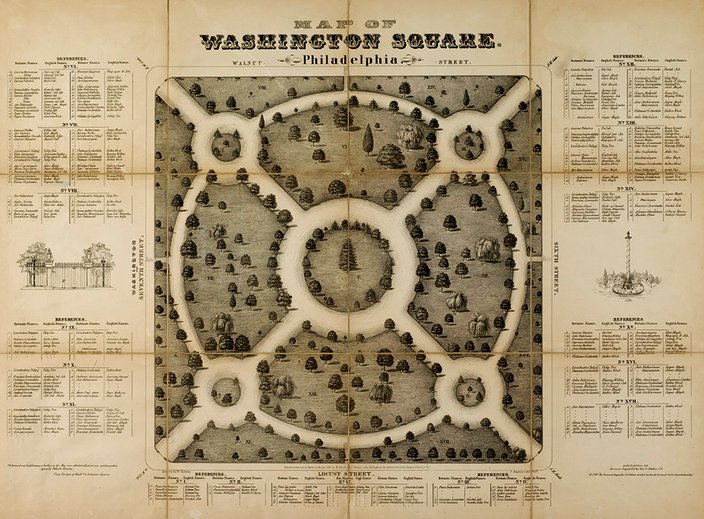

Source/Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Source/Historical Society of PennsylvaniaThis 1842 map of Washington Square highlights the circular walkways and numerous trees comprising the park in the early 19th century.

By 1815, Philadelphians were ready to transform Washington Square into the space envisioned by Penn.

George Bridport's plans called for circular gravel walkways and the planting of native trees — as many as 60 to 70 varieties, creating one of the country's first arboretums.

"There were evergreens in here, which we don't have today, as well as different species of American trees," Fanelli said. "It was an American arboretum.

"There's all kinds of large canopy trees and then smaller trees. Bridport didn't have any flowering trees, like dogwoods or anything we have now. His was a green canopy with a green lawn, more or less."

But by the mid-1880s, Washington Square was due for another change.

The square was revamped to include a nexus of diagonal walkways, covered in flagstone and designed to improve pedestrian traffic flow. Multiple entrances were added and an iron palisade fence, installed in 1837, was replaced with six-inch granite edging around the square. Benches were added at the center.

Monuments to the Civil War once stood in the square, including the Washington Grays monument that was relocated to the Union League. Those monuments were removed in the 1950s, when the Washington Square Planning Commission sought to focus the square's tribute on the Revolutionary War.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceA fountain along the south side of Washington Square is one of many that were installed around the city to provide drinking water for horses, people and small animals. This is the oldest fountain of its kind in Philadelphia and dates back to 1870.

Before streetcars and automobiles rose to prominence, Philadelphians relied on horses to traverse the city. A remnant of that horse-powered era still remains along Washington Square's southern border.

In 1870, The Philadelphia Fountain Society installed the city's first drinking water fountain on the square's northwest corner, at Seventh and Walnut streets. At the time, few public water sources were available for the city's horses and dogs.

But public drinking fountains and water troughs soon began popping up around the city as social reform movements gained momentum. The Fountain Society built dozens of fountains like the one in Washington Square, which was relocated to the square's southern border in 1916 but still runs.

Only a few of those fountains remain today. Some sit without much notice along sidewalks or have been repurposed as planters. A few still spit out water.

The fountains also were intended to add beauty to the city's streets. Many of them included decorative designs or inscriptions.

The fountain in Washington Square once included a decorative tablet topped by a stone eagle. Its inscription reads "Let thy fountains be dispersed abroad, and rivers of water in the streets."

The fountains continued to be installed into the 1940s. But they fell into disuse as automobiles and electric streetcars gained prevalence.

On a related note, the Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Square honors the founder of the Philadelphia Fountain Society, Dr. Wilson Cary Swann.

Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.orgAn aerial view of Washington Square in 1960 highlights the Curtis Publishing Company building, which was constructed half a century earlier.

Washington Square had fallen into decline at the turn of the 20th century as the city continued to expand westward. Municipal offices, once a short walk from the park, now were housed in the Philadelphia's massive City Hall. Rittenhouse Square had established itself as the housing destination of the city's elite.

By contrast, one newspaper noted that "bums and drunks" regularly bothered visitors to Washington Square. Real estate prices surrounding the square dropped.

Yet, a burgeoning publishing scene had taken root.

The square long had housed publishers like the American Bible Society, the Public Ledger newspaper and the Central News Company. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, a member-supported library and British-style reading room, moved onto the square in 1845, constructing one of the first brownstone buildings in the city.

But the arrival of J.B. Lippincott and Company precipitated another publishing boom.

Founded in 1836, Lippincott moved to Washington Square in 1901, erecting a five-story, $158,000 building on Sixth Street after its former home was destroyed by fire. The publishing company was among the largest in the country, printing trade magazines, novels, textbooks and medical books. Over the decades, its monthly magazine featured writing by Jack London and Oscar Wilde, among other prominent writers.

Other publishers, including David McKay Publications, W.B. Saunders Co., Lea and Febiger Company, and Farm Journal, began operating along Washington Square within the next two decades. N.W. Ayer and Son, now regarded as the nation's oldest advertising agency, arrived in 1928.

None matched the prominence of Curtis Publishing, which printed Ladies Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, among other popular magazines. Curtis Publishing moved from New England, demolishing a series of old homes to construct a massive, $3 million headquarters on the north side of Walnut Street in 1910.

These companies flourished in Philadelphia through the mid-20th century, part of a successful publishing industry. But by the late 1900s, many of them had been bought by other publishing companies or relocated elsewhere.

Many of their former buildings have been transformed into condominiums as Washington Square has reverted to a primarily residential neighborhood.

"These companies are not keeping large buildings anymore," Fanelli said. "The Farm Journal is still out there (having moved to the Kansas City area in 2016). But they don't need a big building anymore. People got the idea that, 'Hey, that would make a nice condo.' They just started from there and kept going."

Among the more famous Philadelphians who have called such condos home: former Phillie Chase Utley.