November 12, 2015

Seventy-five percent of what glass artist Matt Szosz makes fails.

Yes, 75 percent.

"[Glass art] is a lot of trial and error, and every time something fails I learn something new -- even if it’s what not to do," Szosz told PhillyVoice. "If something works perfectly, then I didn’t really learn anything I didn’t already know.”

In other words, it's almost a let-down for Szosz when a project is successful, making his work more about the process than the product. It's that innovative and constructive (not to mention humble) approach to making glass pieces that earned him University of the Arts' third annual Borowsky Award, a $5,000 prize for glass artists named after University of the Arts trustee Irvin Borowsky, a publisher and enthusiastic collector of glass art. The award was handed out by a jury of six people that included last year's winner, Bryan Wilson.

As part of the award, Szosz, based out of Washington, will be in Philadelphia to deliver a speech this evening about the significance of process when making art, as well as to create art in Hamilton Hall with students and any local artists interested in observing.

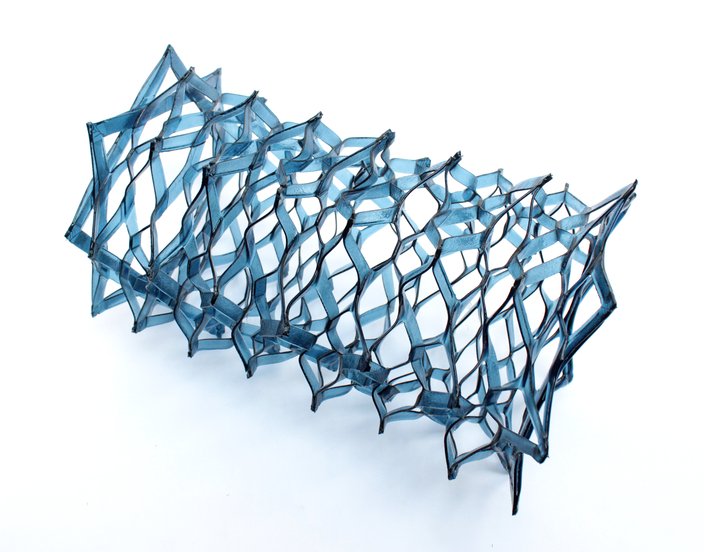

Szosz, who studied glass at the Rhode Island School of Design, has built a reputation nationally as a more experimental glass artist than most. Eschewing the Venetian glassblowing tradition, he instead manipulates glass using techniques from his background in industrial design -- using a kiln and flat glass to stretch and inflate.

Alex Rosenberg, an assistant professor of crafts at University of the Arts, who sat on the jury for the Borowsky Award, describes Szosz as exemplary of a "new breed or generation of glass artists."

"He took what glassblowing was, and the skills he had, and took industrial processes and melded those things together to make something unique,” Rosenberg told PhillyVoice. "One of the main goals of the prize is to offer exposure and support for glass art that’s something a little different than people might expect to see."

Szosz said he approaches his work with no end-game in mind.

"It’s kind of like setting up dominoes, not knowing what the final outcome will be," Szosz explained. "There’s a lot of planning and preparation, and you set these things up that you think are going to interact with each other and you figure it out and see what happens. And then you make your next set of dominoes based on that.”

Much of his glass, in a very literal sense, ends as a pile on the floor.

His fascination with the medium, meanwhile, stems from its transient quality compared to metals and woods.

"For me, glass is almost something that's not there," he said. "It’s a very delicate thing. It’s fragile; it’s transparent. It’s very heavy and very solid, but in other ways very delicate. And historically, unlike pottery, you don’t find that much of it around. It doesn’t tend to survive very long."

That's why he's also taken to recording much of his process -- particularly since so many of his materials end up thrown out. He hesitates to call these videos "performances," instead referring to them as "events."

Szosz will perform one of these demonstrations in the days ahead, alongside University of the Arts students. He hopes to leave something behind but said he often has a high fail rate when working in studios that are not his own.

At 41, Szosz has had his work featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Zane Bennett Contemporary Art gallery in Santa Fe, Calif., and countless other museums and academic institutions across the country.

But he's not a guy who, in truth, cares much about traditional success or lives for accolades like the Borowsky Award -- though he certainly appreciates them when they come along, and embraces the validation. Instead, he seeks out the rush that comes with learning new techniques, watching glass mold into shapes unexpected and taking his passion for glass to both students and the masses.

"I think that, in general, people don’t acknowledge how much glass is in their lives and how many different areas of the world it gets into," Szosz said. "The basic component of glass is everywhere from your iPhone to your windows.”