June 03, 2015

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

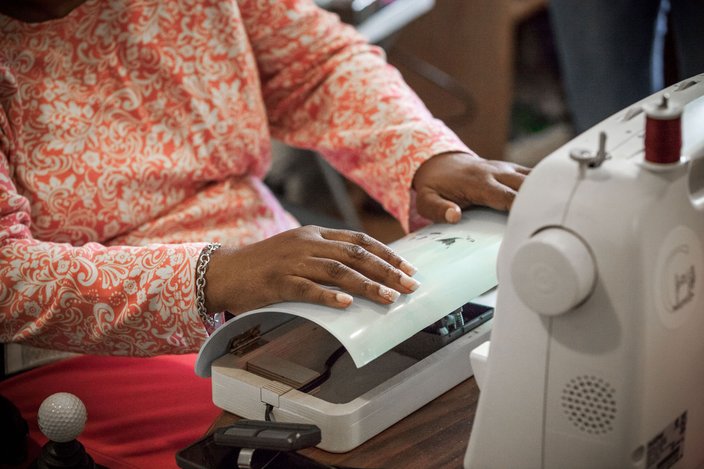

Glenda Speller sits by the sewing machine that students retrofitted to be operated with her arms. She is unable to use the typical foot pedal to operate the machine.

All Glenda Speller wants to do this summer is sew a few seersucker dresses for her great granddaughters, aged two and five. When the 58-year-old West Philadelphia resident does so, though, it will be the first time in 10 years that she’ll be able to enjoy her favorite hobby.

Speller lost the use of her lower limbs in 2005 while her blood supply was cut off too long during a surgery. Since then, she’s had to adapt to performing a host of mundane tasks in new ways.

“...It was stressful. I knew if we weren’t able to deliver, she’d be really disappointed. We didn’t want to fail her.” – Lena Feliciano Hansen, UArts junior

But using a sewing machine has remained elusive since she can no longer operate the foot pedal which moves the needle up and down. She’s tried placing it on the table and pushing it with her hand, but found it difficult to simultaneously apply pressure and guide fabric under the needle.

Now, thanks to a unique partnership between the University of the Arts, Thomas Jefferson University and Liberty Resources Inc., a nonprofit that advocates for those living with disabilities, Speller’s greatest joy has been returned to her.

An interdisciplinary team consisting of two industrial design and two occupational therapy students assigned to Speller crafted the Simple Stitch, a forearm-activated sewing machine controller. All told, seven teams designed and fabricated products — such as an easel, a paint brush holder, and a backpack — aimed at solving specific problems for seven of Liberty’s clients.

The result, Speller says, “has given me back my life.”

For UArts’ associate professor Michael McAllister, who has invited Jefferson professors to his classes before, the idea was “to take design education and make it as real as possible with real world partners and users.”

Lena Feliciano Hansen, 21, a UArts junior who worked on the Simple Stitch, says the best aspect of the project was “getting to know the person we were working with.” Feliciano Hansen and her three team members wound up visiting Speller at her home a few times, and talked frequently with her by phone. “You really have to listen,” she says.

For example, the first things Speller mentioned when the team interviewed her were that her shower leaked and the height of her dining table was uncomfortable.

“These seemed simple enough to fix,” comments Stromer. “We kept pressing her to talk about something more meaningful.”

When they did, things got a little tense.

“Glenda was being very open and chatty about her daily life,” observes Feliciano Hansen. “But when we asked about hobbies, she sort of got quiet, she wouldn’t look at us. It was apparent right away that this was something she really cared about.

“But it was stressful,” continues Feliciano Hansen. “I knew if we weren’t able to deliver, she’d be really disappointed. We didn’t want to fail her.”

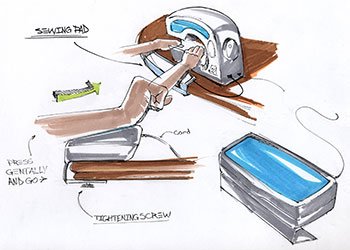

The industrial designers began work on hacking foot pedals so they could gain an understanding of their mechanisms; meanwhile the occupational therapists considered the proper dimensions and angles that would best suit Speller’s body mechanics like her reach, strength and weight.

The designers tossed out a number of ambitious ideas. Maybe they could fashion a sensor that would start the machine when Speller waved her arm over it. Or how about a button that would start the foot pedal?

“In the end, we knew that rather than great concepts what we needed was the simplest feasible solution,” says Stromer. “’We’re taught to be client-centered.”

After a few test versions, they settled on a configuration that offered Speller the most comfort and ease of use. “Basically, we created a new housing for the standard pedal that has the right shape and angles for Glenda,” says Feliciano Hansen. With a plywood base and a smooth, curved thermal-formed acrylic top, the product ”allows her to apply pressure with her forearm and not strain her wrist.”

The single greatest takeaway for the students?

“We’re always told design is about the user,” says Feliciano Hansen. “When I worked with Glenda, I got it. You can sit and sketch at your desk and imagine but until there’s a user involved, it doesn’t matter.”

As for Speller, she can’t wait to get back onto the machine and perhaps start her own sewing business.

“Nothing can stop me now,” she says.