July 03, 2019

When the Tour de France kicks off Saturday, the world's best cyclists will hit the road for one of the top endurance events in the world, traversing 2,162 miles in 23 days. They must summit seven mountaintops, including Col de I'lseran – the highest paved pass in the Alps. They will receive just two days off.

Completing such an event takes a big heart – literally.

Elite endurance athletes tend to have heart cavities that are larger than the general population, even compared to people who exercise regularly, cardiologists say. That enables them to generate the high volume of blood flow needed to sustain an elite pace for a lengthy period of time.

"One single beat in their heart might be the equivalent of 1.5 beats in our hearts," said Dr. Prashant Rao, a former sports cardiology fellow at Thomas Jefferson University who is now at Harvard Medical School. "That allows them to go harder and faster compared to us mere mortals."

Their hearts can be 10 to 30 percent larger than those of the general population, Rao said.

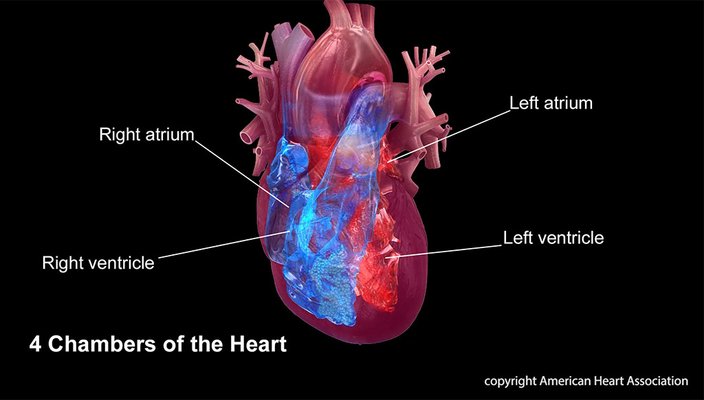

All four heart chambers grow larger in elite endurance athletes – think cyclists, marathon runners and cross country skiers. But the left ventricle particularly can enlarge. As the heart's main pumping chamber, the left ventricle receives oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium, a filling chamber, and pushes it out to the rest of the body.

These changes increase the volume of blood circulated by the body and, in turn, supplies the muscles with maximum oxygen for prolonged periods of time. They do so while maintaining healthy heart rates.

"They have normal ejection fractions, normal squeeze," said Dr. Isaac "Ziggy" Whitman, a cardiac electrophysiologist at Temple University Health System. "The amount of blood they eject out of the heart with every beat is supranormal."

But the world's top athletes typically aren't born with so-called athletic hearts. Studies have shown these physiological changes are the result of intense, prolonged endurance and strength training.

And they're not the only athletes whose hearts change as a result of intense training.

Athletes who engage in more static sports, like powerlifting, tend to have hearts with thicker walls caused by resistance training, but their heart chambers don't increase much in size. By contrast, endurance athletes tend to have thinner heart walls.

Some – like rowers – get a mixture of both changes, said Dr. Neel Chokshi, director of Penn Medicine's Sports Cardiology and Fitness program. The hearts of athletes who play team sports like soccer and basketball may also experience some changes, though typically not as drastic.

All four heart chambers – right and left atria and right and left ventricles – grow larger in elite endurance athletes like cyclists, marathon runners and cross country skiers. But the left ventricle particularly can enlarge.

At Penn, Chokshi's fellow cardiologists follow a chart that outlines the various heart changes typically seen in elite athletes of varying sports. These changes include the growth of chamber size and heart thickness.

"Usually, what we see is some mix of both, depending on the sport and what kind of training the person is pursuing," Chokshi said. "That's a general rule. But that's our approach to it and the pattern seems to hold pretty well."

These changes are not permanent, cardiologists say. The heart regresses to a more typical dimension and thickness when an athlete stops training for an extended period of time.

All this training may prompt some heart problems for some endurance athletes down the road, though cardiologists say the health benefits typically outweigh any risks.

Yet, it begs the question: Is there a point where exercise shifts from being beneficial to harmful?

Research shows that elite endurance athletes have a higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation, an irregular heartbeat atypical among younger adults. People with atrial fibrillation have a heightened risk of stroke, blood clots and other heart-related issues.

Cardiologists don't fully understand the higher risk for atrial fibrillation, Chokshi said. Part of it probably stems from the left atrium enlarging, but there are other possibilities, too.

"Maybe there's more inflammation or fibrosis or scarring in the heart, which we have seen," Chokshi said. "That, coupled with some other reasons – athletes tend to have lower heart rates – sets up a perfect storm for developing atrial fibrillation."

One case study examined more than 52,000 male skiers who completed Vasaloppet – the largest cross country race in the world – over a 10-year stretch. Those who had the fastest finishing times or completed the highest number of races during that decade were associated with a greater risk of AFib.

"Those who go hardest, fastest and longest are the ones who are more likely to get atrial fibrillation," Rao said.

Former Spanish cyclist Haimar Zubeldia, who recorded five top-10 finishes in the Tour de France, developed atrial fibrillation later in his career. At one point, he ceased training for three months before returning to the sport.

Other athletes, including basketball star Larry Bird and tennis player Mardy Fish, also have battled AFib. But any of these athletes – and others similarly affected – may have been genetically predisposed.

Still, the heightened risk remains an association – no causal relationship has been proven.

"Maybe there's something about these people that puts them into endurance sports and, oh by the way, they have increased risk of atrial fibrillation," Whitman said. "It doesn't mean the sport is causing it. Their heart is abnormal, but not in a deleterious way."

Detraining is one way to treat atrial fibrillation, but it's not always the ideal path for ideal athletes, Whitman said. Neither are the standard medications, which blunt adrenaline and increase fatigue.

Atrial fibrillation typically affects older adults. Risk factors include increased age, hypertension, diabetes, coronary disease and obesity. Also, men are more likely to develop atrial fibrillation than women.

Even among elite endurance athletes, the risk remains low. And cardiologists stress that among the younger, general population, the risk of developing atrial fibrillation is miniscule – even if they work out regularly.

"These are guys who, for an hour or hours a day, are at 60 percent or more of their maximum predicted heart rate," Whitman said of the elite endurance athletes. "For you to get your heart rate up to 175 (bpm) and then spend an hour there is really tough. That's the type of person we're talking about here."

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Copyright/American Heart Association

Copyright/American Heart Association