If Philadelphia had an aristocracy, John Thayer was surely part of it.

The second vice president of Pennsylvania Railroad was a fixture on the cricket club circuit before he married Marian Longstreth Morris, the daughter of an old-money iron magnate. The couple lived large on a two-acre estate in Haverford and traveled just as lavishly — sometimes with one or more of their four children.

Their teenage son Jack accompanied his parents on one of these trips in April 1912, but only two of them returned. John perished along with more than 1,500 others aboard the RMS Titanic. Marian made it onto a lifeboat, dying 32 years later to the date of the ship's sinking. Jack was rescued from the frigid water and miraculously survived, though personal tragedies would haunt his short life.

- INSIDE THE ARCHIVES

- PhillyVoice peeks into the collections at different museums in the city, highlighting unique and significant items you won't typically find on display.

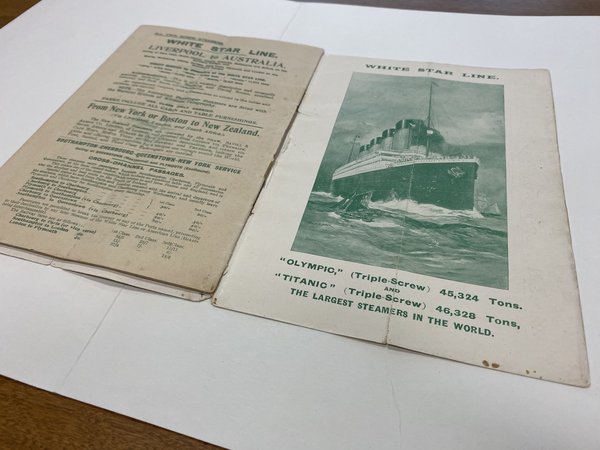

The ship's program that was in Marian's coat pocket survived the terrible night, too, and now it belongs to the Independence Seaport Museum.

The souvenir that Marian carried gives a window into the first-class experience on the doomed ocean liner. The program lists amenities like a squash court, gym, formal restaurant, swimming pool, Turkish baths and "electric" baths — a waterless treatment akin to modern tanning beds. A clothes pressing and cleaning room is also mentioned, though the upper crust never set foot in it; that was a space for their maids and servants, who also traveled on the ship, to iron out finery.

The names of every first-class passenger were also printed on this exclusive document, providing the wealthy an opportunity to flaunt and fraternize. Passengers in steerage did not receive the program.

"These people, they wanted to know each other and know who was traveling with them," said Peter S. Seibert, president and CEO of the Independence Seaport Museum. "You would often make notes on these of people you met. That's why they have sort of wide margins. You wanted to know, was this the Lyons (family) from Newport, or was it the Lyons (family) from New York?"

- MORE INSIDE THE ARCHIVES

- Philly's first queer newspaper published just one issue in the early 1970s and was funded by a drug deal

- This early movie projector started a dispute between the Franklin Institute and Thomas Edison

- How eye drops used to prevent blindness in newborns funded the Barnes Foundation's art collection

These wealthy voyagers could also find scheduled stops on the cruise and rates for renting deck chairs and blankets. A "special notice" warned that professional gamblers often traveled on ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

"In bringing this to the knowledge of travelers, the managers, while not wishing in the slightest degree to interfere with the freedom of action of patrons of the White Star Line, desire to invite their assistance in discouraging games of chance, as being likely to afford these individuals special opportunities for taking unfair advantage of others," the notice read.

The Thayers weren't the only prominent Philadelphians aboard the Titanic. Members of the wealthy Widener family, which made its fortune on the city's trolleys, also booked passage on the ship. George Dunton Widener and his wife, Eleanor Elkins Widener, had actually invited the Thayer clan to a dinner party the night of the ship's crash. The Titanic's collision with the iceberg happened soon after the gathering dispersed. In his published account of the disaster, Jack Thayer did not describe a dramatic boom, just a faint realization that the breeze through his porthole had stopped.

He and his parents remained together on the ship's A Deck until the staff began calling women and children to lifeboats. While Marian and her maid, Margaret Fleming, queued for a vessel, Jack was separated from his family. The ship was sliding faster into the ocean and so, in a moment of desperation, he leapt feet first into the water. Jack then huddled with roughly 30 other people on an overturned raft until a lifeboat picked him up.

The 17-year-old saw his mother again aboard the Carpathia, the British passenger ship that rescued Titanic survivors, the next morning. Neither of them knew what had happened to John. His body was never recovered.

George Dunton Widener and his son, Harry Elkins Widener, also died in the wreckage.

"Until the first world war, that was one of the big game changers with a lot of these families," Seibert said. "Was losing someone there and not being prepared to figure out where all the money went."

The shock of the Titanic sinking spurred improvements in maritime safety, including mandates for 24-hour radio monitoring and enough lifeboats per person. But the cruise industry, Seibert said, changed even more dramatically after World War II. Ships increasingly had to compete with airlines, and while ocean liners like the SS United States could go pretty fast, it was no match for a plane. The industry abandoned destinations like England for the Caribbean and then pivoted to a more populist approach, building out behemoths with super slides and Disney characters — which likely would've appalled the Thayers.

As for that family, its hardships were far from over. Jack, like his father, attended the University of Pennsylvania and married a socialite with ample wealth of her own. But friends later said he suffered a nervous breakdown over the death of his son Edward in World War II. He died by suicide in 1945, two years after Edward's death and one year after his mother's passing.

Marian's program made it to the Independence Seaport Museum through Jack's daughter-in-law, who donated it in the late 1980s. The artifact was displayed in a 2012 exhibit on Philadelphians who sailed the Titanic, but has hidden in the archives over the past decade.

Seibert believes stories like these still fascinate over a century later because the Titanic exposed the stark divide between the first-class travelers like the Thayers — who had access to amenities and at least some lifeboats — and the poorer passengers who had no hope of surviving.

"There's this notion of America as a classless society," he said. "The Brits are class people, they segregate, but Americans aren't. And yet ... there are stories that people who were below decks couldn't even get above deck to try to be saved, let alone to escape the ship because they were locked in down below.

"We don't like that. We want that sense of we're a classless society. We should have all had the chance."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.