January 30, 2017

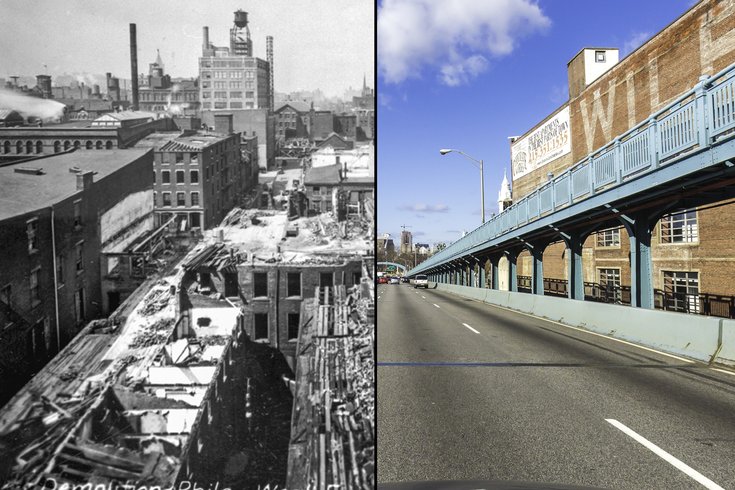

DRPA, left; Thom Carroll, right/PhillyVoice

DRPA, left; Thom Carroll, right/PhillyVoice

The Ben Franklin Bridge then and now: On the right is the section of the bridge in Old City that westbound motorists see as they cross the Delaware River into Philadelphia. To the left is a photo of the buildings that were being demolished in 1924 to make way for this portion of the bridge. See complete versions of both images below.

January marks 95 years since construction began on the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, and you wouldn't even know it.

It's hardly changed a bit – at least that's what Mike Howard, a senior engineer at the Delaware River Port Authority and co-author of the book, "The Benjamin Franklin Bridge," says.

But the iconic suspension bridge – which has become a symbol of Philadelphia as much as the Liberty Bell and LOVE statue – has a lot of history packed into its twisted steel cables despite its nearly untouched exterior, to hear Howard tell it.

"For the most part, it's pretty much the same," Howard said. "Some of the real, true things about the bridge that people don't know about is what's not seen."

Like the 15 men who died during its construction and the trolley tracks originally laid on its deck as an alternate means of transportation across – there's a lot you might not know about the bridge that transports so many commuters from Philadelphia to Camden, and back, every day.

To illustrate just how much the cities at both ends of the bridge have changed, while the bridge itself mostly has remained the same, PhillyVoice photographer Thom Carroll recreated 10 historic photos taken during the construction and early days of the Ben Franklin Bridge's history. The older photos in each pair were provided by the DRPA archives or PhillyHistory.org. .

West Tower and Race Street Pier as they look in 2017.

.

View looking west on the Ben Franklin Bridge, near the former Wilbur Chocolate factory building, right, in Old City.

During its construction from 1922 until its dedication in 1926, what is now known as the Ben Franklin Bridge was named the Delaware River Bridge. When the Walt Whitman Bridge was built, but before it was named, officials knew with two bridges crossing the Delaware River there'd be some confusion with the generic name.

Howard said the Ben Franklin Bridge was renamed in 1955 for the U.S. Founding Father and inventor who lived in Philadelphia, while the Walt Whitman Bridge was named after the humanist and writer who died in Camden.

"Ben Franklin's buried a block away from the bridge, so it seemed an obvious choice," Howard said.

.

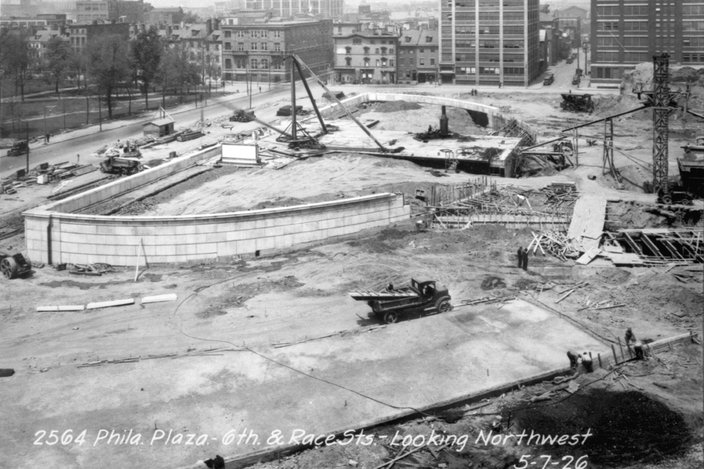

The view of Philadelphia Plaza, looking southwest, as it appears in 2017.

At the peak of its construction, 1,300 people worked on the bridge, and during the four years it took to build, 15 lost their lives in construction-related incidents.

For example, Howard Meyer, a 29-year-old man and former World War I pilot, died after an acetylene torch exploded in his hands, knocking him backward off the bridge and into the Delaware River in May 1926.

Two people died in another incident in May 1925. As Howard described it, John Viti, 24, fell into the water, and another construction worker, Robert Flynn, 39, dove in after him. Both men got sucked into the propellers of a tugboat on the Delaware below. .

Camden toll plaza looking northwest as it looks in 2017.

The bridge cost about $37 million to build, with funding coming from New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as well as Camden and Philadelphia, which paid for the physical parts, real estate acquisition and demolition.

The Ben Franklin is made from 760,000 tons of structural steel and masonry. When it opened, it had the longest single span of any suspension bridge in the world, with a length of 7,456 feet from abutment to abutment. It held that title for three years, until 1929, when the Ambassador Bridge in Detroit opened in 1929.

"We don't speak about that bridge," Howard said jokingly.

.

The view looking west over the Ben Franklin Bridge from the Philadelphia Plaza in 2017.

.

The tall ship Gazela, docked at Penn's Landing in Philadelphia.

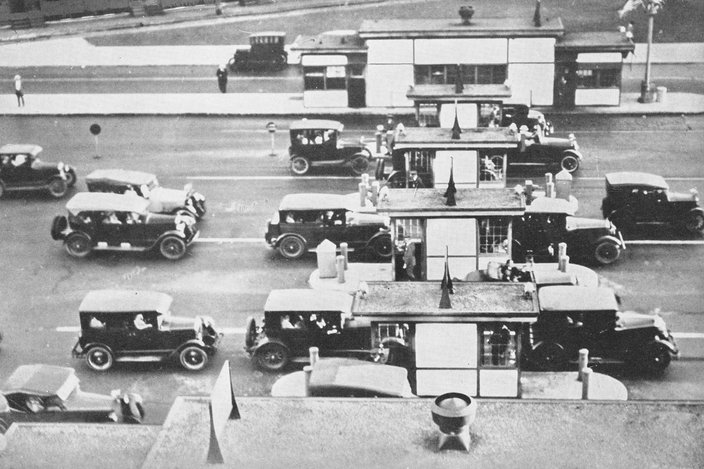

When the Delaware River Bridge opened in July 1926, the toll fare was just a quarter for cars and 15 cents for horses – yes, horses and buggies were allowed to cross the bridge, too, Howard said. Allowing horses to mingle among the cars crossing the bridge was done away with in the bridge's early years.

"Obviously, the time it takes a horse to cross the bridge was significantly longer than a car," Howard said.

.

Looking northwest from Camden toll plaza in 2017.

Howard said there was one incident when a horse approached an expansion joint of the bridge and became so "spooked" that it refused to move until the owner threw a coat over its head and coaxed it to move forward.

Today, the toll is $5 for cars crossing the bridge, paid as motorists head west before crossing from Camden to Philadelphia. An estimated 100,000 vehicles cross the bridge daily.

The Ben Franklin Bridge had eight traffic lanes across when it opened – two were paved with trolley tracks and the remaining six were for cars. The trolley system had never come into fruition, Howard said, and the tracks were paved over giving, the bridge eight lanes for vehicles.

As cars became bigger and wider, the Port Authority re-striped the bridge, reducing it to the seven traffic lanes it has today.

.

A tugboat is seen on the Delaware River from Penn's Landing in Philadelphia.

.

The view south from the Ben Franklin Bridge near where Front and Summer streets formerly existed.

The bridge's anchorages were to house trolley stations, Howard said. A large transit hub was planned at the end of the bridge at Sixth Street on the Philadelphia side.

"A whole form of transportation pretty much disappeared," he said.

.

This photo shows Independence Mall in Old City. In the distance, the Ben Franklin Bridge can been seen.

For more facts and statistics about the Ben Franklin Bridge, visit the Delaware River Port Authority's website. For more photos, view the gallery below.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice

Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice

Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/ PhillyHistory.org

City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/ PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org

City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice

Delaware River Port Authority/for PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org

City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org

City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org

City of Philadelphia, Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice