April 20, 2017

Photo illustration by Thom Carroll, (black and white image, Library of Congress, color image, Thom Carroll)/PhillyVoice

Photo illustration by Thom Carroll, (black and white image, Library of Congress, color image, Thom Carroll)/PhillyVoice

This image combines photos taken at 21st and Lehigh streets in North Philadelphia. The black-and-white portion was taken in 1933 and shows Shibe Park, the former home of the Philadelphia Phillies and Athletics. The rest of the photograph shows the same corner as it appears in 2017. Today it is the location of Deliverance Evangelistic Church.

Baseball is as much about the ballparks where it's played as it is about who's playing the game. Memories of first games, heroic feats, crushing losses and those rare historic victories are inseparably intertwined with the places where they took place.

The setting is a character in the story, like with a good book.

In Philadelphia, the long history of professional baseball has had a cast of characters – some good, some bad – with the Phillies, Athletics and others. Below are photos of some of the ballparks and stadiums where the game has been played in the city.

The historic photos come from several different sources: the Temple University Libraries Special Collections Research Center (found here on Facebook), PhillyHistory.org, the University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center and the Library of Congress.

PhillyVoice photographer Thom Carroll recreated the historic photos to show what those locations look like today.

The Old Athletic Field near 36th and Spruce streets on the University of Pennsylvania's campus in West Philadelphia was only a temporary home for the Philadelphia Phillies. In 1894, the team played six games there – winning five – while repairs were being made to their usual home ballpark, the Baker Bowl, which had been damaged in a fire.

At the time, the Phillies were managed by Arthur Irwin, who had played professionally for the Phillies, Providence Grays and Worcester Ruby Legs, among other teams. In 1894, he was coaching the Phillies and Penn's varsity baseball team.

This photo taken in 1891 shows the University of Pennsylvania's baseball team practicing at the college's Old Athletic Field at 36th and Spruce streets in West Philly. The Philadelphia Phillies played six games here in 1894 after the Baker Bowl (originally known as Philadelphia Baseball Park) was damaged by a fire. The Phillies manager that season was Arthur Irwin, who also was Penn's varsity baseball coach at the same time.

This is the view today looking northeast at 36th and Spruce streets. The location, formerly the University of Pennsylvania's Old Athletic Field, remains part of the college's campus but now is occupied by buildings.

The Philadelphia Athletics played their home games at Columbia Park from 1901 to 1908. The ballpark was in the city's Brewerytown neighborhood on a rectangular block surrounded by 29th Street, Columbia Avenue (since renamed Cecil B. Moore Avenue), 30th Street and Oxford Street.

Rich Westcott wrote on PhiladelphiaAthletics.org that it cost $35,000 to construct Columbia Park, and the seating capacity when it opened was 9,500. With the A's success, seating capacity increased. It was 13,600 by 1905, and during that season's pennant chase, a record 25,187 fans packed Columbia Park.

The Athletics were managed by Connie Mack, and according to Westcott, Mack lived across the street from the stadium in a house at 2932 Oxford St. Many of the Athletics players moved into Brewerytown, as well.

Columbia Park also was known as the Columbia Avenue Grounds. The Phillies played 16 games there in 1903 after a portion of the balcony at the Baker Bowl collapsed.

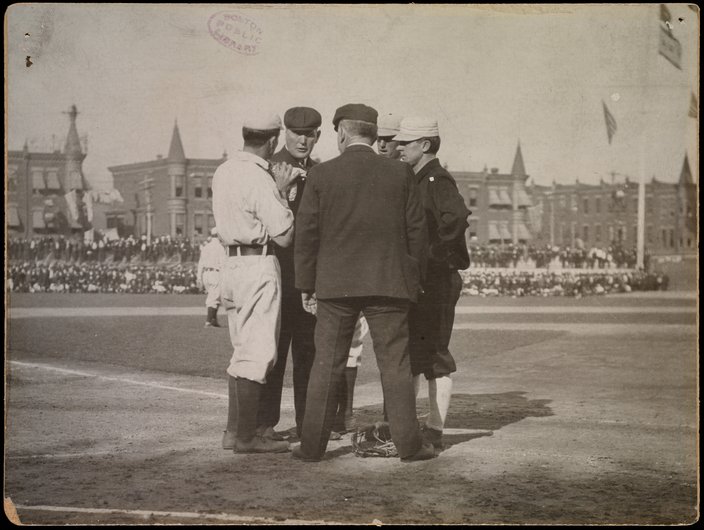

Umpires and members of the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Giants meet at home plate during a 1905 World Series game at Columbia Park in Philadelphia's Brewerytown neighborhood.

This pair of rowhomes at 29th Street and Cecil B. Moore Avenue in Brewerytown matches those seen beyond the outfield stands of Columbia Park in a photo taken during the 1905 World Series between the Athletics and Giants.

Rowhomes on the 2900 block of Oxford Street in Brewerytown stand in the exact location of the former Columbia Park baseball stadium. This photo looks northeast from where home plate was located. In the early 1900s, the stadium was home to the Philadelphia Athletics and, for one season, the Phillies.

Located in North Philadelphia on Broad Street between West Huntingdon Street and West Lehigh Avenue, the Baker Bowl was the home ballpark for the Phillies from 1887 to 1938. It was built to fit inside a city block, which resulted in some funky playing field dimensions.

As it was originally configured, the boundary of the entire outfield was defined by a brick wall standing at least 20 feet tall. That height compensated for a short right field, where the wall was just 310 feet away from home plate. But the left field wall stood about 500 feet away. Legend is that no batter ever hit a ball out of the Baker Bowl's original field.

Except for the brick walls in the outfield and those on the stadium's exterior, the Baker Bowl was constructed almost entirely of wood, which was not unusual for stadiums built in the late 19th century. On Aug. 6, 1894, the Phillies were practicing there when a fire erupted in the grandstand and engulfed the wooden structure, leaving nothing standing except those masonry walls.

The Phillies owners rebuilt the Baker Bowl, erecting a state-of-the-art cantilevered pavilion of steel and brick in time for the start of the 1895 season.

But a worse tragedy struck on Aug. 8, 1903, during a doubleheader with the Boston Braves. After fans rushed to see a disturbance taking place in the third-base-line balcony, the sudden shift in weight caused a portion of the Baker Bowl's upper deck to collapse, killing 12 people and injuring more than 200.

Yet, the Baker Bowl's lasting mark on baseball is something fans take for granted today – the right to keep foul balls that land in the seats. Major League Baseball adopted the policy in 1923 after 11-year-old Robert Cotter refused to hand over a ball he had caught during a Phillies game. Cotter was arrested and spent the night in jail before a judge dismissed the charges.

The Baker Bowl was known by several names during its history – first Philadelphia Park or Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds, then its formal name was Philadelphia National League Park, and it frequently was called the Huntingdon Street Grounds.

Philadelphia Phillies fans line up outside the Baker Bowl in North Philadelphia, waiting to get inside to see the team's last game there on July 1, 1938, before its move to Shibe Park at 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue.

The intersection of 15th and Huntingdon streets in North Philadelphia as it looks in 2017. This is the former location of the Baker Bowl, where the Phillies played for more than 50 years.

A police officer directs traffic outside the Baker Bowl in North Philadelphia in a photo taken July 1, 1938.

At the 44th and Parkside ballpark in West Philadelphia, players would lose fly balls in the coal smoke billowing from the trains in the neighboring Pennsylvania Railroad train yard – and sometimes conditions got so bad that games had to be delayed.

Philadelphia Stars catcher Stanley "Doc" Glenn wrote in his autobiography about how much he disliked playing at the Stars' home field in the smoky conditions:

"It was filthy. Coal-powered trains used to pull in nearby at Belmont and Girard avenues for cleaning, then roll back downtown to the main station at 30th Street. Smoke and soot used to waft right into the ballpark. Why, if you went outside with a white shirt on, 20 minutes later that shirt would turn black!"

The field's location was not by accident. Pennsylvania Railroad's management built the stadium in 1906 for its YMCA-sponsored employee football team, the Railroaders, but it was best known as the home park for the Stars, who played there beginning in 1936.

Philadelphia has a rich history of professional black baseball, and the Stars were one of the city's most popular teams following their formation in 1933. In 1934, the Stars joined the Negro National League. They won the Negro League Championship that year.

Some of the Negro League's greatest players, like Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell and Satchel Paige, took the field at 44th and Parkside. In 1947, Paige legendarily pitched eight perfect innings. Then, in the ninth, he intentionally walked the first three batters, instructed his fielders (except the catcher) to sit down and proceeded to strike out the next three batters on nine pitches.

The 44th and Parkside ballpark also was known as Penmar Park and the PRR-YMCA Athletic Field.

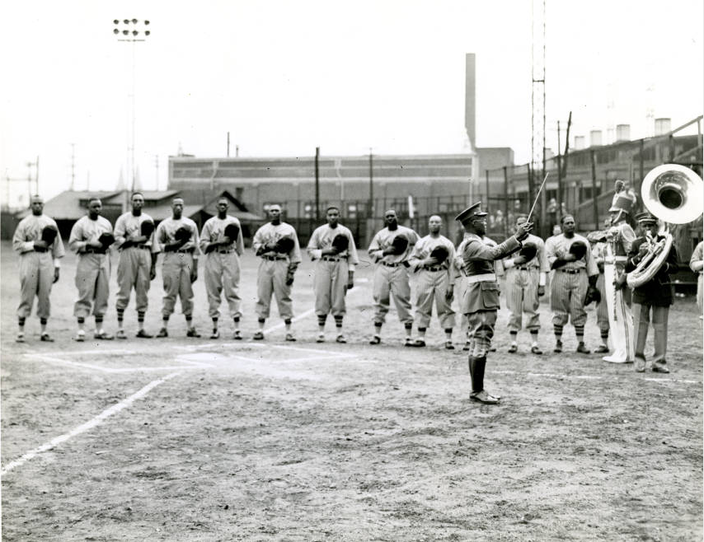

In this photo taken in the 1940s at the 44th and Parkside ballpark in West Philadelphia, a band performs while players from the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League stand with their hats over their hearts.

A historical marker and a mural created by the Philadelphia Mural Arts Program – seen in the background of this photo – show the location of the old 44th and Parkside ballpark in West Philadelphia. The stadium was the home field of the Philadelphia Stars and other Negro Leagues baseball teams.

This undated photo taken in the 1940s at the 44th and Parkside ballpark shows an unidentified batter for the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League just after hitting a pitch.

A bronze statue of a Philadelphia Stars player stands near Belmont and Parkside avenues in West Philadelphia. The statue is in Philadelphia Stars Memorial Park, which is located on part of what was the 44th and Parkside ballpark.

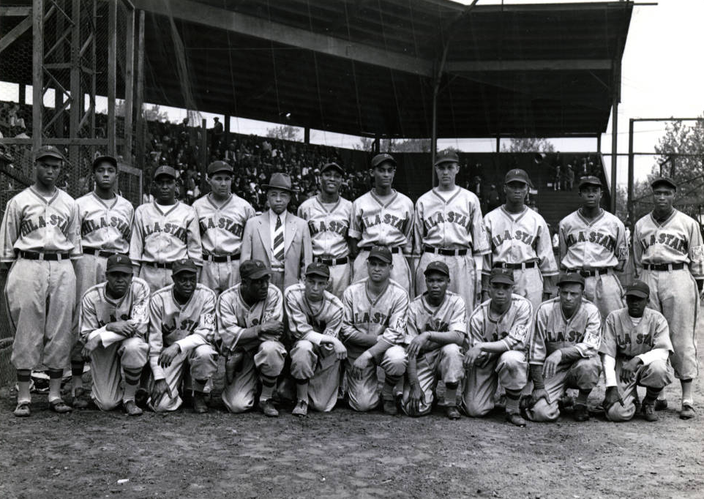

This photo taken in 1944 at the 44th and Parkside ballpark in West Philadelphia shows the players of the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro National League. The team's owner, Ed Bolden, dressed in a suit, can be seen near the center of the image. Bolden also owned the Hilldale Daisies who played in Yeadon, Delaware County, and founded the Eastern Colored League.

Philadelphia Athletics owner Benjamin Franklin Shibe built Shibe Park in the early 1900s to capitalize on the growing popularity of his American League franchise. He chose a location at 20th Street and Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia, five blocks west of the Baker Bowl where the Phillies played.

The property was easily accessible by the trolley lines along Broad Street, and, maybe more importantly, the land was cheap because one block west stood the Philadelphia Hospital for Contagious Diseases, also known as the "Smallpox Hospital."

Shibe Park opened on April 12, 1909, to glowing reviews for its design, baseball historian James Lincoln Ray wrote:

The exterior of the stadium was more French palace than ballpark. Outside the grandstand, an ornate brick façade had huge arched windows separated by Ionic pilasters, decorative friezes with baseball motifs, and gabled dormer windows on the upper deck’s copper-trimmed green-slate mansard roof. Figurative sculptures in terra cotta of Shibe and co-owner/manager Connie Mack peered out over the main entrances. Other entrances were decorated with the letter “A” carved in Old English script.

Initially, the stadium had 23,000 seats and could accommodate an additional 17,000 spectators in two standing-room-only sections. Mack set up his office on the top floor of Shibe's signature tower.

In the middle of 1938, the Phillies left the deteriorating Baker Bowl for Shibe, and on May 16, 1939, the A's played the first night game ever in the American League there, losing to the Cleveland Indians, 8-3.

Mack retired as the Athletics manager in 1950, and in 1953, Shibe's children, who were running the team then, renamed Shibe Park to Connie Mack Stadium. The Athletics were sold a year later and relocated to Kansas City before the 1955 season. Phillies owner Bob Carpenter bought Connie Mack Stadium for $1.7 million, and his team played there through the 1970 season.

This photo of the entrance to Shibe Park was taken in 1909. The stadium at 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia was renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953.

The intersection of 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia is now the location of Deliverance Evangelistic Church. It formerly was the site of Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium, the ballparks of the Philadelphia Phillies and Athletics.

Baseball fans sit atop the roofs of rowhomes on the 2700 block of North 20th Street in North Philly on Oct. 9, 1914. From their perches they can see into Shibe Park across the street and watch the Philadelphia Athletics and Boston Braves play Game 1 of the 1914 World Series. The Braves beat the A's 7-1 in the game and went on to win the series in a four-game sweep.

These rowhomes on the 2700 block of North 20th Street, once located across from the outfield wall of Shibe Park, still stand in 2017. During games, fans would gather on the roofs to watch the games.

As beloved as Veterans Stadium was among Philadelphia Eagles fans, those feelings about the stadium didn't translate to baseball.

It was a cavernous bowl of an arena at Broad and Pattison – many of the Vet's 62,000-plus seats were too far from the field, and the playing surface was artificial grass. The planning for the multipurpose palace began in 1952 with the proposal for a $7 million stadium to be built in South Philadelphia. Due to labor strikes, rising construction expenses and bad weather, Veterans Stadium cost $52 million to complete by the time it opened for the season in 1971.

The exterior of the Vet remained mostly the same during the stadium's 33-year lifespan. Inside, two digital scoreboards above the left- and right-field fences eventually were replaced by the "Phanavision" video scoreboard; dancing water fountains in the outfield came and went; and luxury suites were constructed, ringing the top of Veterans Stadium's infamous 700 Level.

Among the notable events that occurred at the Vet, the Phillies clinched the 1980 World Series against the Kansas City Royals. They lost two others, in 1983 and 1993, while playing there.

Demolition crews imploded Veterans Stadium on March 21, 2004, and shortly afterward, the Phillies christened Citizens Bank Park on April 3, 2004.

Veterans Stadium in South Philly, the home field for the Philadelphia Phillies from 1971-2003, is shown in this photo taken April 7, 1970. In the foreground is the Spectrum, which closed in 2009 and later was demolished.

In 2017, the Veterans Stadium site is a parking lot immediately west of the Phillies' current home, Citizens Bank Park. And the Spectrum site is another lot just north of the Wells Fargo Center.

Does this stadium look familiar? It shouldn't. This is an undated architectural rendering of a design considered for Veterans Stadium in South Philly. Construction on the stadium began in October 1967 and it opened in April 1971. When this image was published, there was a debate whether to include a roof in the design of the stadium.

Contributed photo/From the Collections of the University of Pennsylvania Archives

Contributed photo/From the Collections of the University of Pennsylvania Archives Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of Boston Public Library/digitalcommonwealth.org

Courtesy of Boston Public Library/digitalcommonwealth.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa. Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa. Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa. Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa. Contributed photo/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Contributed photo/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Contributed photo/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Contributed photo/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Philadelphia Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org

Philadelphia Department of Records/PhillyHistory.org Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pa.