February 11, 2019

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

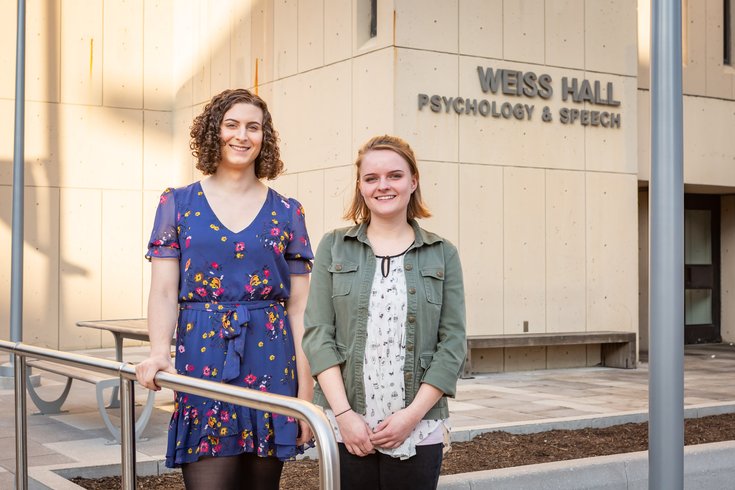

Erica Cirulli, left, stands alongside one of her voice therapy coaches, Hilary Waller, on the campus of Temple University in North Philadelphia.

Erica Cirulli described the beginning of her transition from presenting as a man to a woman as a methodical one.

She identified several "pillars" on which to focus initially, including coming out to people as a transgender woman, beginning hormone therapy treatments and undergoing laser hair removal.

Cirulli, 29, of Philadelphia, also wanted to change her voice, which she described as "super deep," even though it did not cause her dysphoria.

"It didn't cause me that kind of grief or angst at the time," Cirulli said. "But I knew if I was going to be presenting this way, I couldn't walk around talking like I used to. I wouldn't have felt comfortable and a lot of people probably wouldn't have felt comfortable around me. Which is sad, but it's the truth."

The Mazzoni Center, an LGBTQ health care provider in Center City Philadelphia, referred Cirulli to Temple University's Speech-Language Hearing Center, which houses a student-run, voice therapy clinic that regularly assists transgender women who want to alter their voices.

There, Cirulli found her new voice.

"This was a game-changer for me," Cirulli said. "It impacted my confidence, the way I carried myself and how capable I felt of myself to be able to communicate effectively, efficiently, confidently. This program changed everything for me."

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceErica Cirulli, a transgender woman who received voice therapy at Temple University's Speech-Language Hearing Center, spent hours practicing techniques at home. 'It's not that hard to ... focus on a higher pitch and talk with that higher pitch,' she says. 'But to shift where your voice vibrates is really tough.'

Temple's Speech-Language Hearing Center, which serves as the clinical component to the university's speech-language-hearing graduate program, offers several speech-language services for students to gain required clinical hours.

Its voice therapy clinic assists people with an array of voice disorders, including those caused by nodules on the vocal cords, neurological problems and bowed vocal cords.

But it also has served the transgender population for as long as the clinic's director, Ann Addis, can remember. And she's been there since 1978.

The clinic is small, operating every Wednesday and serving about 12 clients per semester. Yet, it is one of the few clinics in the Philadelphia area that specifically caters to the transgender community.

Source/Temple University

Source/Temple UniversityAnn Addis is the director of the voice therapy clinic at Temple University's Speech-Language Hearing Center.

"The point is two-thirds of the bloc is transgender and I have a huge waiting list," said Addis, an instructor of communication sciences and disorders at Temple's College of Public Health. "There aren't many people working with this population and they're hearing about us through the internet and the Mazzoni program."

One big benefit to clients: Due to Medicare regulations, the program is free.

By contrast, professional services can be expensive and are not always covered by insurance. Vocal cord surgery offers another pricey alternative, but Addis said it has not proven effective.

"Most of our clients, I'd say they average two semesters," Addis said. "They're coming once a week for (one) hour sessions. I was in private practice for over 20 years. We were charging over $100 an hour for a session."

The clinic tends to see far more transgender women than transgender men, Addis said. That's primarily because transgender women outnumber transgender men. Plus, hormone therapy treatments naturally lower the voices of transgender men.

"When they start taking male hormones, the vocal cords get larger ... and their pitch drops," Addis said. "They don't need therapy."

But the transgender women who receive voice therapy at the clinic find something truly unique, Addis said. Clinicians provide a welcoming environment by working to understand the needs of clients and offering support as the women continue in their transition.

"It's important for trans people or families of trans people to know that there are services out there from people who understand what they're going through," Addis said.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceAs a graduate student at Temple's Speech-Language Hearing Center, Hilary Waller helped Erica Cirulli acquire a more feminine voice by adjusting her pitch, resonance, intonation and body language.

The first two therapy sessions for transgender women include preparation of a detailed case history identifying aspects of a female voice important to the client and outlining the ways her voice is regularly used.

For instance, someone who speaks loudly and frequently – or who wishes to sing with regularity – might require a different approach than a soft-spoken, computer technician who does not utilize her voice as often.

After thorough discussion, the student clinicians help the women establish attainable voice goals.

"Not knowing much about speech therapy, my initial goals were to sound like a girl and also, much more subjectively, make it sound like it's my voice," said Cirulli, an accountant. "Not just a female voice. It has to sound like it's mine."

Clients complete a baseline voice sample that is measured for pitch, breath support and other voice factors.

"One of the reasons that this is really good is that you get objective, quantifiable data to start with," said Hilary Waller, 26, a Temple graduate who provided therapy to Cirulli as a grad student. "You can make goals that are very easy to measure and just give you a baseline and an area where you want to end."

From there, the clinicians walk the women through various drills aimed at adjusting their pitch, resonance, intonation, breathy phonation and body language. They tinker with these characteristics to create a more feminine voice – and one that each woman finds most natural to them.

"It's not that hard to ... focus on a higher pitch and talk with that higher pitch. But to shift where your voice vibrates is really tough." – Erica Cirulli

Step-by-step, the clinicians help the women make incremental adjustments to their voices, avoiding injury as they master new vocal techniques. They gradually move from simply reading short phrases to having full-on conversations, essentially connecting their voice to their speech.

For Cirulli, finding the right combination of pitch and resonance proved integral. Whereas male voices generally resonate in their chest, female voices tend to resonate in their head space.

"It's not that hard to ... focus on a higher pitch and talk with that higher pitch," Cirulli said. "But to shift where your voice vibrates is really tough."

Cirulli spent hours practicing techniques at home.

Initially, Cirulli only was presenting as a woman in her personal life. When she later came out professionally, she began using her new voice everywhere. That provided more opportunities to use her voice and helped her gain greater comfortability.

"Once I did go full-time and I was presenting as myself, as a woman, around my personal and professional life, I was able to hit the ground running," Cirulli said. "It just made everything easier."

Cirulli cannot pinpoint exactly when her new voice came to form. But at one point, she realized everything had clicked, describing it almost as an epiphany.

"It was like a lot of other moments that I had, where I made steps in the direction of who I wanted to be, how I wanted to look, how I wanted to sound," Cirulli said. "That was just another one of those reaffirming moments for me."

During her interview with PhillyVoice, Cirulli played a short recording of her former voice followed by her current, feminine voice. The two samples sounded like they were from different people.

Such success stories are not uncommon, Addis said. Some clients have even referred others to the clinic.

"Outcomes are generally good," Addis said. "Clients are satisfied and people like Erica make you think, 'Wow, you can make a huge change in someone's life.'"

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.