February 22, 2017

Earl Gardner/Philly Soccer Page

Earl Gardner/Philly Soccer Page

The Philadelphia Union played a 4-2-3-1 in all 34 league games last season.

Question: What's the best way to protect a deep-lying playmaker with defensive limitations?

Answer: Build your system around him.

If you watched Saturday's 1-0 win against Tampa Bay, you probably noticed Haris Medunjanin's ability to get on the ball and pick out incisive, forward passes. It really looks similar to the way that Andrea Pirlo plays the game, with foresight in distribution and the capacity for building from back to front.

Like most ball movers, Medunjanin is probably not a guy who's going to pull off a 30-yard defensive sprint, put in a crunching slide tackle, and win the ball for his team. The onus will always be on a midfield partner or pair of center backs to cover for any defensive frailties in that regard.

Stylistically, the Union are committed to a 4-2-3-1 system that emphasizes strength in numbers, coordinated team movement, and rigid shape. To the credit of Jim Curtin and his coaching staff, you saw the club take a step forward last season in developing an identity as an organized pressing team.

That system won't change, but I really do think this team has the pieces to build a 3-5-2 around Medunjanin.

It would look something like this:

At full health, you've got two wingbacks who are fit enough to move up and down the flanks. You have three mobile defenders to shield a deep-lying ball mover. You've got a pair of hard working box-to-box midfielders and two goal-scoring strikers.

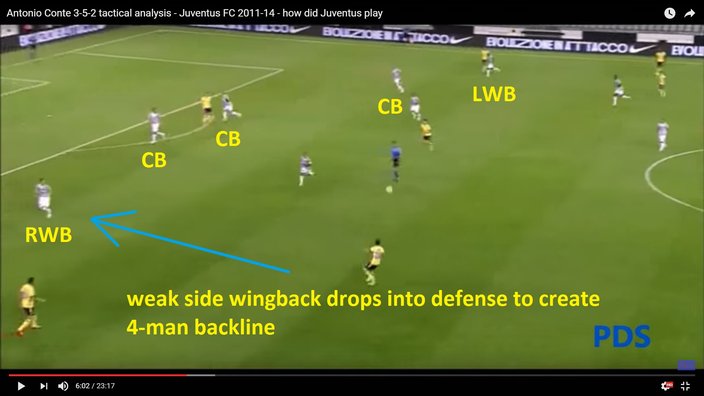

It's a shape that copies what Juventus successfully played under Antonio Conte from 2011 to 2014.

Here's what it looked like during the 2012/2013 season:

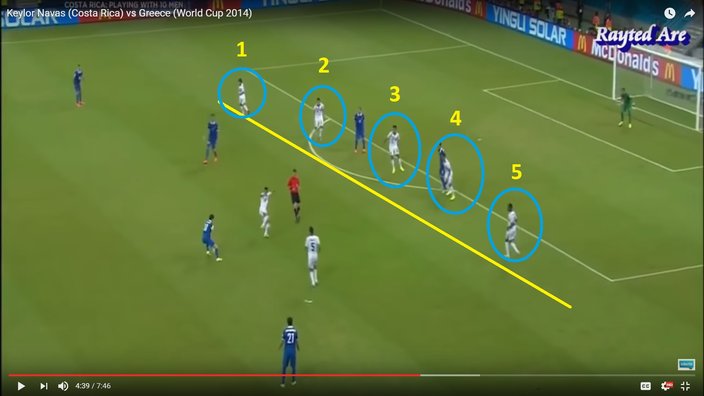

The 3-5-2 saw a slight resurgence in the 2014 World Cup. The most notable teams to use that shape were probably the Netherlands, which advanced to the semifinals, and Chile, which exited in the knockout rounds. Mexico also used the formation, which you often see in their domestic league.

Here's how the Netherlands and Chile typically played during the tournament:

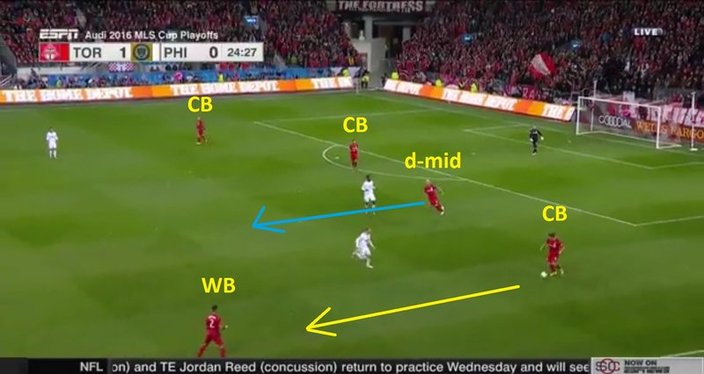

We don't see a ton of 3-5-2 in MLS. Toronto installed the system last summer and played it in the MLS Cup final, but they were the only team in the league to give it a try. With a squad full of stars, and an under-appreciated defense, the really did find a lot of success with the shape.

This is how they came out in the playoff game against Philly back in October:

You might remember Jose Luis Sanchez Sola, or "Chelis," the Mexican coach who had a short stint at Chivas USA. He used a Liga MX-style 3-5-2 in Los Angeles, but just didn't have the players to make the shape run successfully.

Most teams in MLS are running a 4-2-3-1 or 4-3-3 these days, which is also what you see internationally. Those systems are probably easier to play than a three-man defense.

One of the tricky things to learn about the 3-5-2 is that wingbacks have defensive responsibility in specific situations. Typically, when one wingback moves forward, you'll see the weak side wingback rotate into defense. This is an example of that, with the ball moving to the opposite side of the field and Stephan Lichtsteiner dropping into defense to help the center halves and create a back four.

The 3-5-2 is a fun shape to watch, and it can be wildly successfully with the right players on the roster.

I do think the Union have those pieces in place.