August 21, 2019

Kim Green lab/University of California Irvine

Kim Green lab/University of California Irvine

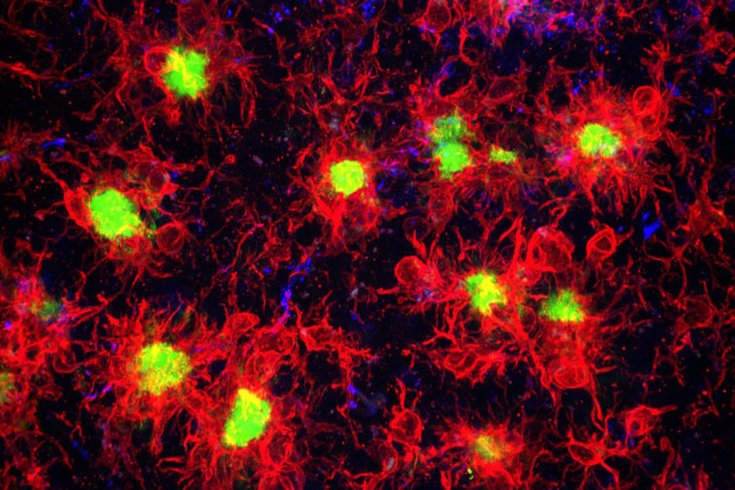

Microglia, shown in red, surround and react to the amyloid-beta plaques, shown in green, in the Alzheimer’s disease brain, in this image provided by the University of California Irvine.

Researchers at a California university have discovered a way to forestall Alzheimer’s disease in the laboratory, offering hope that targeted drugs could one day prevent the debilitating disease.

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine School of Biological Sciences found that removing brain immune cells, or microglia, from mice kept beta-amyloid plaques – the "hallmark pathology" of the disease – from developing, according to a news release about the findings.

The study appears in the journal Nature Communications.

Previous research had established that microglia could play a role in the disease.

“However, we hadn’t understood exactly what the microglia are doing and whether they are significant in the initial Alzheimer’s process,” said Kim Green, associate professor of neurobiology & behavior. “We decided to examine this issue by looking at what would happen in their absence.”

Green and his team used a drug that blocks microglia signaling that is necessary for their survival, building on their prior findings that "blocking this signaling effectively eliminates these immune cells from the brain," the release said.

“What was striking about these studies is we found that in areas without microglia, plaques didn’t form,” Green said. “However, in places where microglia survived, plaques did develop. You don’t have Alzheimer’s without plaques, and we now know microglia are a necessary component in the development of Alzheimer’s.”

Another discovery: when plaques are present, microglia see them as harmful and attack them. But that attack also switches off genes in neurons needed for normal brain functioning, researchers said.

According to Green, the discovery suggests future drugs may be developed to prevent the disease.

“We are not proposing to remove all microglia from the brain,” the professor said, noting that the microglia play a role in regulating other brain functions. “What could be possible is devising therapeutics that affect microglia in targeted ways.”

The National Institutes for Health provided support for the research, which was performed in collaboration with Plexxikon Inc., a Berkeley, California company.