The Pennsylvania Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement now lists eight Philadelphia cases on its dangerous dogs registry, a listing designed to inform the public of any dangerous canines living within the neighborhood.

That marks a change from one month ago, when the registry did not list any dangerous dogs from Philadelphia.

Inquiries by PhillyVoice revealed the Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement had not been receiving consistent and complete reports from Philadelphia.

Both state and city officials have indicated a desire to change that, pledging to ensure the requisite agencies report necessary information to the bureau.

The bureau uncovered 27 Philadelphia cases, dating back to 1997, following an inquiry last month by PhillyVoice. The bureau determined eight of those cases remain active and posted them to its dangerous dog registry.

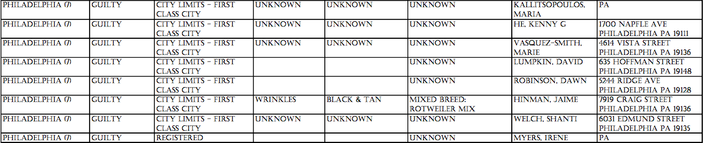

Yet, only one of those cases includes complete documentation on the registry, which requires the dog’s name, color, breed, owner and address. Seven cases do not include the dog’s breed. Another two do not include a specific address.

“As you know, we are working to strengthen our communication with Philadelphia and we will address this as a part of that communication,” said Brandi Hunter-Davenport, press secretary of the Department of Agriculture, which oversees the Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement.

These are the eight Philadelphia cases listed on the dangerous dogs registry published by the Pennsylvania Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement. Much of the data required to be reported is missing from the registry.

The Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement also mailed a letter to the Philadelphia Police Department regarding its role in reporting dangerous dog cases, Hunter-Davenport said.

The letter, dated April 8, directed police to provide the bureau with information on any individual charged with harboring a dangerous dog. The bureau enclosed a copy of a form that is to be used, which seeks the dog’s owner, address, name, breed and description.

A copy of the letter also was mailed to the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office as a courtesy, Hunter-Davenport said.

The letter states that anyone charged with harboring a dangerous dog is subjected to “significant requirements.” Failure to adhere to them results in further criminal charges.

“The Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement informs those charged with harboring a dangerous dog of the requirements that must be met,” the letter states. “The bureau, therefore, requests you notify it when your department charges a person with harboring a dangerous dog.”

Philadelphia police did not immediately respond to request for comment.

Dogs are declared legally dangerous when a judge determines that an unprovoked dog attacked, injured or killed a human or domestic animal. The judge is required to report that determination to the Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement, according to the Pennsylvania Dog Law.

Owners are subjected to stringent regulations, including a $500 annual registration fee, restitution and a $50,000 liability insurance policy. Dogs must receive a microchip, be spayed or neutered, and be muzzled and leashed when off the owner’s property.

On Saturday, a three-year-old girl was mauled by a family dog while visiting her grandmother in West Philadelphia. The girl was mauled on the head, according to NBC10, and underwent surgery. She was listed in critical condition. The Cane Corso did not have a prior history of aggression and police said the owner is unlikely to be charged.

The eight active Philadelphia cases now listed on the dangerous dogs registry differ from two cases cited by city and animal control officials last month after inquiries from PhillyVoice.

Tara Schernecke, assistant director of operations for Animal Care and Control Team (ACCT), a non-profit agency contracted by the city, said those two cases are considered “very active” because they occurred within the last year.

But Schernecke now acknowledges the city also has older, active cases in which ACCT conducts required inspections to ensure dangerous dog owners are adhering to all regulations. She could not provide the exact number offhand, but said the eight cases cited by the Bureau of Dog Law Enforcement sounded accurate.

ACCT does not have a role in reporting dangerous dog cases to the state. The agency handles cases after dogs are declared dangerous by a judge.

“We’re not involved in any of that stuff until it’s actually declared dangerous,” Schernecke said. “Then, we jump on board.”

Yet, Schernecke said the various agencies are still adjusting to changes brought by the elimination of Philadelphia’s dog warden in 2011, including the timely reporting of dangerous dogs.

Philadelphia First Deputy Managing Director David Wilson, who oversees the city’s animal control efforts, did not respond to calls seeking comment.