February 29, 2016

On Sunday night, in Hollywood, people who make a healthy living from working in lands of make believe bathed in tubs of justifiable overcompensation.

You had Chris Rock, host of an Academy Awards ceremony (and history) shrouded in racial-disparity controversy, clasping his jaws around the issue and not letting go until well after his point had been justifiably, effectively made. (Rock acknowledged this in saying African-Americans “had real things to protest at the time” to explain why 2016 finally became the year for the loud #OscarsSoWhite uprising before he lost some moral steam via Girl Scout cookies-skit shticks.)

You had Leonardo DiCaprio, a straight-up player with all-time acting chops who had gone unrewarded at times when he should’ve been lauded finally snaring a golden statuette for his work in “The Revenant,” a tribute to vast cinematography in which he spoke sparingly. (Some observers position the award as a make-up call celebrating years of excellence in his field – ahem, “What’s Eating Gilbert Grape” – and they’re right.)

You also had Academy voters naming as their best picture of the year “Spotlight,” a gut-punch of a film about journalists speaking truth to Roman Catholic Church power on behalf of the victims of an institution’s life-shattering inclination to protect sexual predators who preyed on the young and vulnerable in Boston and beyond. (For the film, victory was positioned an “upset” even though it wasn’t. It stands as a painful reminder of what print journalists had more success doing before the Internet cornered markets on classified advertising and exclusive breaking-news reach.)

There’s something inherently poetic about Stallone’s character losing in the end. It’s true to character form, the whole rising up from relative obscurity to fight a great fight and lose out on the judges' scorecards.

But what Philadelphia, in particular, didn’t get Sunday night was a chance to wake up and smile with the realization that the actor responsible for a fictional-boxer statue/tourist attraction was rewarded for a resonant role in a career’s latter stages.

I’m typing, of course, about Sylvester Stallone in the film “Creed,” a wonderful advancement in the 40-year-old Rocky Balboa saga. Its inaugural film won the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Film Editing in 1976. Still, Stallone’s nominations for Best Actor and Best Original Screenplay remained just nominations thanks to Peter Finch and Paddy Chayefsky (“Network”), respectively.

In a year that the "Rocky" franchise’s latest installment, “Creed,” stood as a shining example of shifting a storyline from a white protagonist to an African-American one, a Stallone win was perceived – by myself and many others, in gambling parlance – as a stone-cold mortal lock. This was also fueled by Stallone’s Best Supporting Actor wins in the Golden Globes and Critics’ Choice Movie Awards.

On my way to the Oscars… It's been a most memorable year. https://t.co/uSAppiu5dl

— Sylvester Stallone (@TheSlyStallone) February 28, 2016

In recent weeks, the 69-year-old wondered aloud whether he should even attend the ceremony, what with the film itself and its director, Ryan Coogler, getting snubbed. He also noted that if he did win, he’d dedicate the win to Tony Burton, aka Duke, the trainer of foe-turned-friend Apollo Creed who died last week.

Some chalked the loss up to personal beefs; others said it had to do with his foe’s quality.

Still, I loved “Creed.” Teared up as Stallone’s boxer battled cancer and the rigors of time passed. Celebrated as Michael B. Jordan continued evolving and excelling in his years since Wallace on “The Wire.” But, today, understood that local biases fueled the favored status.

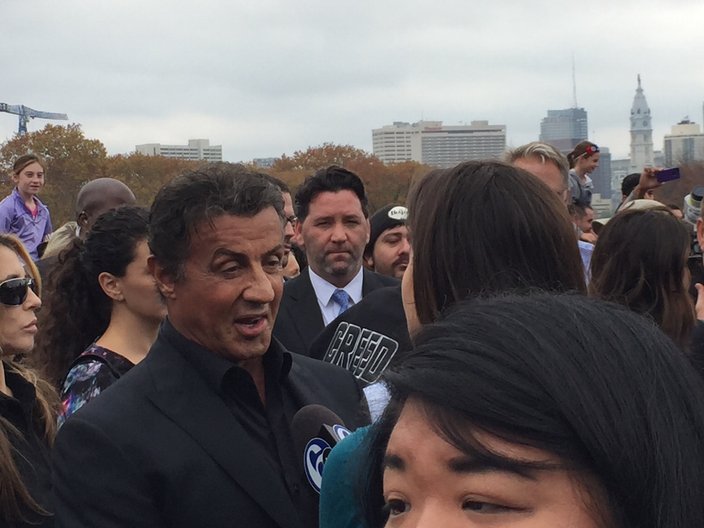

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoiceActor Sylvester Stallone returns to the 'Rocky Steps' outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art for a promotional event regarding the new film 'Creed,' which will be released in theaters on Nov. 25, 2015.

Unlike DiCaprio, though, Stallone’s body of work isn’t exactly that of thespianic legend. “Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot.” “Tango & Cash.” “Judge Dredd.” “Over the Top.” (Fine, fine, that last one represents the peak of arm-wrestling lore.)

While surprised and disappointed as a Philadelphian, I think there’s something inherently poetic about Stallone’s character losing in the end. It’s true to character form, the whole rising up from relative obscurity to fight a great fight and lose out on the judges' scorecards.

By not winning the big prize, but basking in the adulation of a job well done, Stallone is more honorarily Philadelphian than ever before.

We don’t need pats on the back to know we’re tough, and Stallone doesn’t need an 8.5-pound statuette to know he’s made a creative difference locally and beyond.

Would it have been nice for him, and our city, to see photos of Stallone holding the actor honor over his head? Sure, just like how the 2008 Phillies resonate greater than the predecessors from 1993.

Still, all Sunday night did was add to that 40-year-old lore, buttressing the theme that losing can represent a bigger victory than winning. Here's hoping Sly already knows that.