On St. Patrick's Day in Philadelphia, there are two very different kinds of revelers. The first lines up along Benjamin Franklin Parkway with their family and friends and watches groups of Irish dancers parade down the street.

Children celebrating with their parents just blocks away from co-eds puking up Guinness and Bailey's is common enough each year. But traditionally, the holiday was not celebrated this way. In fact, the designation of March 17 as a drinking holiday is incredibly recent.

As a day of religious observance for the Irish, St. Patrick's Day has its roots in the 5th century. Patrick was a Brit enslaved by the Irish in the mid-400s who escaped to his home after six years. Upon returning, Patrick had a dream in which he was called back to Ireland to convert its people to Christianity, which he made his life's work. He is said to have died on March 17, and thus, his legacy is celebrated that day.

In Ireland, the day has largely been observed with a religious feast and holiday; businesses close and families attend Mass. In fact, for decades, pubs had to be closed on that day due to the Intoxicating Liquor Act of 1927. It was repealed in 1962, mainly in the name of tourism. Only in the 1970s did it become popular for pubs to be open in celebration. Though smaller parades have always flourished around the country, the first official St. Patrick's Day Festival only came to Dublin in 1996.

The American-Irish, though, have always celebrated St. Patrick's Day more rambunctiously. English rulers first invaded Ireland in the 12th century. Rebellions periodically broke out on the island for centuries, but tensions peaked in the 16th century when the Protestant Elizabeth I ascended to the English throne. From then on, Irish Catholics were persecuted and discriminated against, unable to freely practice their religion for centuries. Though a relatively minor celebration at home, Irish immigrants feted St. Patrick's Day in their new land simply because they could.

Thus, New York City held the first parade for the day in 1762, and Philadelphia quickly followed with a parade in 1771 thanks to the Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, of which George Washington was made an honorary member in 1782.

"When [the Irish] came here, they really enjoyed the fact that they were in a free society and they could do what they wanted. They could celebrate their religion, their culture by having parades," said Thomas Lyons, an historian and board member of the Friendly Sons.

At the time when the parade first began, Friendly Sons focused on aiding emigrants from Ireland who were settling into the U.S. Today, the non-denominational organization does the same, in addition to providing scholarships, fundraising for charity and maintaining local interest in their cultural heritage. Philly, after all, has a strong Irish community. According to census estimates, those identifying themselves as having Irish ancestry make up 11 percent of the city population, higher than any other single country of origin.

The parade, the second oldest of any kind in the nation,

was officially incorporated in 1952 and has been hosted by the St. Patrick's Day Observance Association ever since. Now it sees more than 150 participating organizations, with thousands of spectators attending each year.

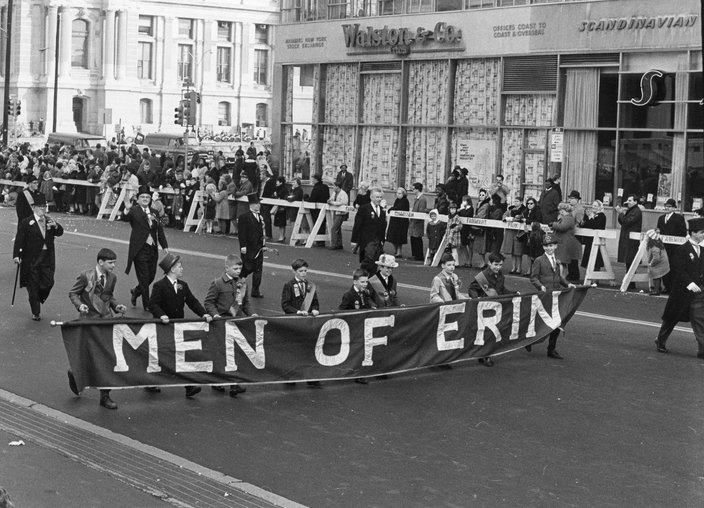

St. Patrick's Day Parade 1967. Irish Philadelphia/Tom Keenan

Michael Bradley, the Parade director, has been with the parade for 25 years and directed it for 13. In his time as director, he's seen its audience grow exponentially. He partially credits this to the popularity of Riverdance, the theatrical show featuring Irish dance and music, in the mid-90s. Riverdance, Bradley said, encouraged many young girls and boys to try their hand at the tradition and form new dance troupes.

"I think that had a lot to do with encouraging the Irish people to reach out to their roots in America," Bradley said. "All over the world, really."

Around this time, however, a different kind of St. Patrick's Day celebration also began to take hold: the commercialization of the day by pubs and bars. Whether the boom in Irish cultural appreciation is a cause or effect of this parallel development is difficult to pinpoint. However, Lyons and Bradley both agree that around the mid-80s and early 90s, St. Patrick's Day began its mutation into boozy revelry.

One local tradition that helped support that image is

Erin Express, the popular bar crawl that shuttles young drinkers around to various bars. The original Erin Express was started more than 30 years ago by the owners of

Cavanaugh's,

Smokey Joe's and Mace's Crossing. According to Brian Pawliczek, whose family has owned Cav's since 1934, it all began with some older men in Irish sweaters traveling to local bars on the Fairmount trolleys with a few guitars.

"The first years were lean," Pawliczek told PhillyVoice.com. "Things began to grow. Trolleys turned into buses. Two guys playing guitar turned into bands; older crowd became younger. Things tend to grow and evolve."

About five years ago, Pawliczek began getting block party permits for those days, turning 39th Street between Chestnut and Walnut into one big drink fest just steps from the Penn and Drexel campuses. Cav's and the nearby bar Blarney Stone sell beer for scary-low prices, set up port-o-johns and hire DJs to spin all day. The recently-defunct Drinker's West on the same block once added to the mayhem.

Now, the "official" Erin Express, as it dubs itself, draws thousands of college students and recent graduates and takes them to 16 bars on free buses. The madness ensues over the course of two Saturdays leading up to St. Patrick's Day, with buses running from around noon until 6 p.m.

The "other" Erin Express, run by National Event Management, links rowdy, touristy sports bars like McFadden's, Voltage, Gunners Run and Crabby Cafe. Revelers can pay $20 to ride this route, which runs noon to 9 p.m. and stops at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for the "Running of the Micks," an offensively-named, dangerous drunken dash up the front steps. This deal runs the three Saturdays before March 17 and includes a special party at the Piazza at Schmidt's on its final day.

As those who neighbor these establishments know all too well, with St. Patrick's Day often comes police sirens, piles of smelly waste and stumbling students. Unfortunately for the community's more wholesome celebrants, these festivities reinforce the centuries-old stereotype of Irish people as drunkards.

"I think there’s a stereotype, probably from the early 1900s with the British and the Irish and they just really hated them, and I think they promoted that," Bradley said. "If five people get arrested on St. Patrick’s Day, it seems like it makes the newspaper... I think it’s exaggerated a little bit...there’s no question there’s a lot of younger people drinking on St. Patrick’s Day, but they’re also probably drinking every Friday and Saturday night, too."

While the Irish community may not be thrilled about the city's annual pub crawls, Lyons said they aren't trying to totally separate themselves from it.

"It’s been highly commercialized," Lyons said. "[Bars and beer companies] saw it as a business opportunity and they jumped on it. That’s what kind of drives that. It’s not so much the Irish society and the Irish people. It’s the commercial opportunity that bars and beer companies today – the same as other holidays - try to capitalize on, like Cinco de Mayo. ... It’s not something that the Irish community supports or promotes. It’s just what evolved out of some business opportunities."

The 1967 St. Patrick's Day Parade. Irish Philadelphia/Tom Keenan

Though both Bradley and Lyons acknowledge there has always been some drinking involved in St. Paddy's, the two maintain that prior to the boom of beer-fueled activities, the day was a family affair. Bradley remembers getting to wear a green tie to school for the day when he was a child and has photos of his mother watching his father march in the parade in 1956. Lyons celebrated with his family as a child, and now he, his wife and his granddaughter all march in the parade.

One organization is looking to put the happy, wholesome aspects of the holiday back into focus.

Sober St. Patrick's Day, which hosts alcohol-free, family-friendly parties, held its inaugural event in 2012 in New York. Started by a TV and theater producer who lost a family member to addiction, the organization has expanded to seven cities worldwide.

This year will be the first time

it hosts an event in Philadelphia.

Sunday, March 15, there will be a night of traditional Irish music and dance at WHYY with snacks, baked goods and tea, coffee and soda standing in for alcohol.

Though Sober St. Patrick's Day helps those who have struggled with addiction celebrate, it also works against the holiday's bad press. The mission statement says it all: "To reclaim the true spirit of the day and to change the perception and experience of what St. Patrick's Day can be by providing family-friendly, alcohol free events that celebrate the depth of Irish culture."

The New York event has sold out three years in a row. If the idea catches on in Philly, it's possible the local Irish community can shed its ties to the drunken debauchery that floods the city each March. Until then, if you see a bus full of inebriated co-eds unloading on the sidewalk, maybe walk the other way.