November 26, 2018

University of California Tobacco Archives/CC BY-SA

University of California Tobacco Archives/CC BY-SA

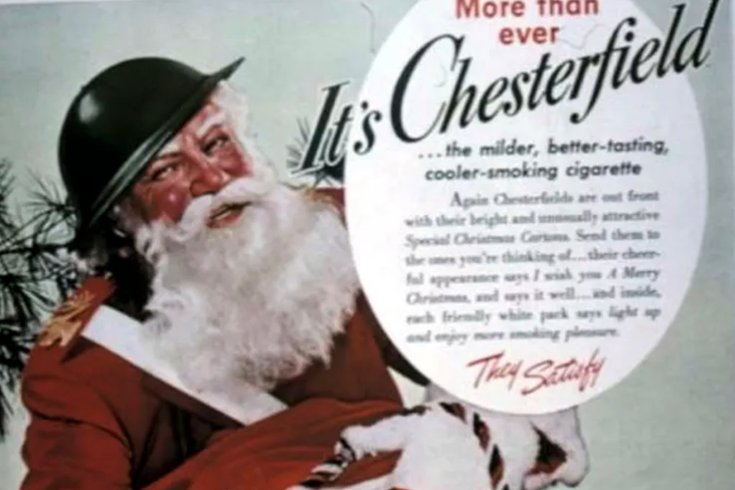

This ad from the World War II era encouraged people to send Chesterfields to men in the armed forces.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls cigarette smoking “the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the U.S., accounting for over 480,000 deaths per year.” The CDC just announced that smoking rates among U.S. adults have fallen to the lowest level ever recorded – only 14 percent, less than a third the rate just 70 years ago. While this decline is remarkable, it also points to a puzzle: How did smoking rates ever get so high in the first place?

November is Lung Cancer Awareness Month, which provides a timely opportunity to review the history of tobacco smoking and its promotion.

Tobacco smoking originated in America around 3,000 B.C. Seafaring traders introduced it to Europe and Asia in the 17th century. One of the first anti-tobacco publications ever issued was King James I’s 1604 “Counterblaste to Tobacco,” in which he condemns the practice as “loathsome to the eye, hatefull to the nose, harmefull to the braine, and dangerous to the lungs.”

Smoking has several appeals. First, tobacco naturally contains nicotine, an insecticide, which raises alertness, speeds reaction times, and stimulates the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, which are associated with pleasure. Second, smoking may provide opportunities to flout authority and fit in with peer groups. Third, once someone has started smoking, attempts to stop may precipitate withdrawal symptoms such as headaches, nausea, anxiety and weight gain.

Cigarette smoking in the U.S. really caught fire in the first half of the 20th century. Technology played an important role. Through most of the 19th century, each cigarette had to be rolled by hand, which took about 15 seconds. But in 1875, a Richmond, Virginia, company offered a $75,000 prize for the invention of an automatic rolling machine. The prize was claimed by James Bonsack, whose machine could roll 200 cigarettes per minute, dramatically increasing capacity and lowering production costs.

Over the course of World War I, cigarettes supplanted pipes as the most popular means of tobacco consumption. Soldiers who smoked pipes had to keep their loose tobacco dry, take time to fill their pipes, and relight them frequently, which could attract enemy attention. By contrast, cigarettes were quick and easy to consume. Free cigarettes were distributed to the troops, and they soon began serving as a unit of currency, with the price of a haircut, for instance, set at two cigarettes. During the war, rates of smoking tripled.

During World War II, free cigarettes were again distributed to soldiers and even included with ration kits. Soldiers were encouraged to smoke to relieve boredom and improve morale, and in 1943 their demand helped U.S. companies manufacture 290 billion cigarettes. Some tobacco ads showed patriotic wives and mothers shipping cartons of cigarettes to their loved ones on the front. At home, rationing made cigarettes scarcer, and on days they were available, people often lined up to buy them.

U.S. tobacco companies received an unexpected boost during WWII when Germany’s Nazi Party introduced a variety of initiatives aimed to reduce smoking among both the general public and physicians. Perhaps augmented by Hitler’s personal distaste for the habit, smoking was banned in many public places, the tobacco tax was raised and educational initiatives were launched. After the war, U.S. cigarette firms were able to undermine anti-smoking campaigns by linking them to Nazi tactics.

For decades, cigarette companies strenuously denied that smoking is linked to human disease. A 1954 ad that appeared in over 400 U.S. dailies was entitled “A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers.” It declared that “interest in people’s health is a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in business.” Yet it also added, “We believe the products we make are not injurious to health,” claiming that “one by one” charges that cigarettes are injurious “have been abandoned for lack of evidence.”

Tobacco companies were not content merely to deny that cigarettes are harmful. They also used print, radio, and television ads to argue that they are positively healthful. Many ads featured physicians and dentists endorsing particular brands because they were filtered or mentholated. One 1930 Lucky Strike ad claimed that “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating,” calling them “Your throat protection against cough.”

Many campaigns featured celebrity endorsements. One 1947 Chesterfield ad featured popular comedian Bob Hope, saying “Dorothy Lamour is my favorite brunette. Chesterfield is my favorite cigarette.” A 1950 Chesterfield holiday campaign showcased actor and future U.S. President Ronald Reagan, a cigarette dangling from his lips, saying “I’m sending Chesterfields to all my friends. That’s the merriest Christmas any smoker can have.”

To promote sales to men, campaigns linked cigarettes to masculinity. The Marlboro Man, conceived by advertising executive Leo Burnett in 1954, aimed to enhance the male appeal of filtered cigarettes, which had a feminine connotation. Running from 1954 to 1999, Marlboro ads featured rugged cowboys on the open range, often backed by bold music, such as the theme from the film, “The Magnificent Seven.” Ironically, many of the Marlboro Men eventually succumbed to tobacco-related diseases.

In the years following World War I, cigarette companies had been disappointed to find that smoking was much less popular among women than men. They soon turned to advertising to stoke demand. One campaign, “torches of freedom,” was developed by Sigmund Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays, who paid young women to light cigarettes during a 1929 Easter parade, symbolizing their emancipation. By 1935, cigarette purchases by women had more than tripled.

By the 1970s, women’s cigarette marketing often focused on themes of liberation. For example, Virginia Slims, which sponsored the women’s professional tennis tour, often promoted images of irrepressible young women with the tag line “You’ve come a long way, baby.” The implication? By lighting up, women could strike a blow for an oppressed minority, announce their independence, and cast their lot with a svelte cadre of role models.

Cigarette use has fallen to an all-time low in part because the last television cigarette ad appeared at 11:59 p.m. on Dec. 31, 1970, just one minute before a federal ban went into effect. But cigarette marketing is not dead. For example, many point-of-sale campaigns can be found in convenience stores, gas stations and even pharmacies. Such promotions now account for most of the $8.7 billion U.S. cigarette marketing budget.

Although cigarette marketing has declined considerably since its heyday, the timeliness of its lessons remains undiminished. Americans today are still subjected to marketing for a variety of hazardous products, from firearms and gambling to less obvious threats such as social media, the excessive use of which is linked to depression. So long as there is money to be made in moving such merchandise, it seems, someone will be on hand with a battery of techniques to promote sales.![]()

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.