May 27, 2024

Provided Image/Jake Schuster

Provided Image/Jake Schuster

Jake Schuster, right, was diagnosed with melanoma three years ago. He underwent immunotherapy for 12 months and received a checkpoint inhibitor – treatments that have helped reduce skin cancer death rates. Schuster is pictured with his girlfriend, Bria Hocking.

Jake Schuster had been the star first baseman of North Penn High School's baseball team. He was playing for Marywood University in Scranton when he noticed that a birthmark on his ankle had grown larger and changed shape. His mother suggested having it removed and biopsied, just to be safe.

Then Schuster got a call that changed his life: he had melanoma. Scans revealed it had spread to nearby lymph nodes.

"Once I hung up the phone, it was like, 'OK, well, this is actually legit,'" Schuster recalled. "You're just beyond scared about what could happen, what's going to happen, what's going on? Because it's crazy, because it's all just going on inside your body, and you can't control it. That was the scariest part."

Schuster, now 26, had surgery to remove the growth above his ankle, causing a deep wound that required a skin graft. Then came immunotherapy infusions, once a month for 12 months, during which Schuster received a checkpoint inhibitor to help his immune system locate and attack melanoma cells. Schuster's treatment was a success, and three years later, he remains cancer free.

Schuster, of Lansdale, said knowing that he had a "humongous supporting cast" around him, including family and friends, using his athletic training to get back in shape as soon as possible, and maintaining a balanced perspective helped him through his treatment.

"What I always thought about is that there were people out there that were in way worse spots than even I was in right now," he said.

Dr. Lynn Schuchter, director of the Tara Miller Melanoma Center at Penn Medicine and one of the doctors who treated Schuster, was impressed by his positive attitude and energy.

"He did so well with the treatments," Schuchter said. "He went to school. He worked out. He's an amazing, amazing young man."

The five-year survival rate for a cancer like Schuster's has increased to 74%. Scientific advances led to immunotherapy, which Schuster received, and targeted therapies called BRAF and MEK inhibitors, which go after proteins that commonly drive the growth of melanoma. These approaches revolutionized melanoma treatment, offering physicians tools beyond surgery, chemotherapy and radiation. After rising steadily since the 1980s, death rates from melanoma declined 17.9% from 2013 to 2016.

"I've been doing this for 30 years, so for almost half of my career I did not have very effective therapies," Schuchter said. "And then suddenly" there was "this whole option of treatments, and we've been very fortunate at Penn to participate in a lot of the clinical trials, so we had much earlier access to some of these treatments.

"I say we had a lot of tears in the clinic, and now we have tears of joy."

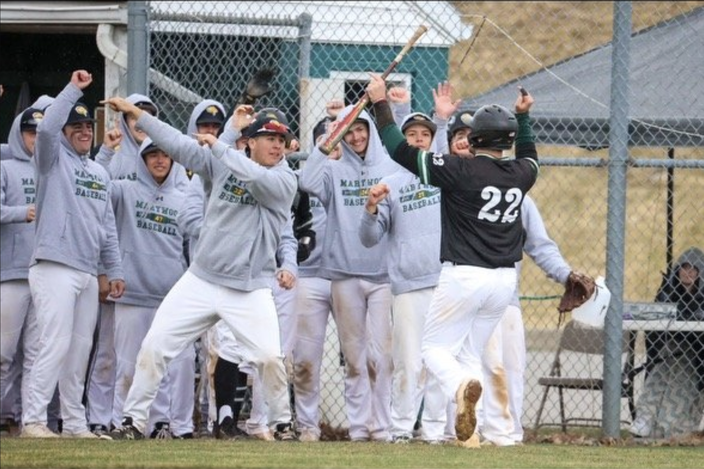

Provided Image/Jake Schuster

Provided Image/Jake SchusterJake Schuster, No. 22 above, was a star first baseman in high school and college. Three years after being diagnosed with melanoma, he is cancer free and coaching Little League.

Still, the American Cancer Society estimates that about 100,640 new melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States in 2024, with 8,290 people expected to die from the cancer.

Changes in the rates of new melanomas vary by age and sex. In people younger than 50, the rates have been stable among women and have declined by about 1% a year in men since the early 2000s. In people ages 50 and older, rates increased in women by about 3% per year but have stayed stable among men.

Risk factors include exposure to ultraviolet rays, having lighter skin, having a lot of moles, and having a family history of melanoma or atypical moles, known as dysplastic nevi.

Research is underway to figure out how to stimulate the immune system through a vaccine strategy and how to use artificial intelligence to improve whole body scans to detect atypical moles that need to be removed and biopsied, for instance, Schuchter said. She emphasized the need for people to protect themselves from ultraviolet rays by wearing sunblock and other methods and for those with a lot of moles to see a dermatologist for advice.

"We haven't solved this completely," Schuchter said. "We've made huge progress, but that's why continued investment in research and new approaches is needed.

"But Jake's just the beneficiary of research that went on a decade earlier, so that we could apply these new treatments to his situation."

Schuster said he recognizes how fortunate he is. He is coaching Little League baseball, working at a baseball facility, studying for his property and casualty license, and enjoying time with his girlfriend, Bria Hocking.

"It definitely changes your perspective on just about everything in life," Schuster said about his diagnosis and treatment. "Honestly, of the 365 days out of the year, I really just never go to bed upset anymore, like annoyed or anything anymore. Because in reality, there's no point. Life's too short as it already is. I'm glad I learned those things at the age of 23."