Moira Bohannon froze mid-bite at the dinner table when her 10-year-old son uttered "the P-word."

"He also mentioned something about how cats and dogs might have babies," she told PhillyVoice, laughing. "You don't even know where to go with something like this."

Bohannon said that her son, who will enter fourth grade at Kearney Elementary School in Northern Liberties, could have used an age-appropriate sex-ed lesson well before now. Starting in second grade, she added, he came home with a schoolyard vocabulary -- certainly language much worse than "the P-word" -- and a wealth of knowledge about every part of his anatomy, all except the ones that may come to shape his looming transition into adulthood.

"They’re clearly talking about [sex] on the playground and the misinformation is clear, but when they’re 7 or 8 years old, they don’t know what they’re saying," she said.

"By the time they're in ninth grade, it’s re-education. And in many cases, too late."

That kind of misinformation spread among peers prompted sexual health nonprofit Access Matters to develop an app that satisfies curiosity and clears confusion. It targets teens and young adults, but its ambition is to develop a culture that will start spreading medically accurate sexual health information.

“It was time to add this tool to our toolbox," Melissa Weiler Gerber, CEO of the Center City-based organization, told PhillyVoice. "Being able to use an app on the school bus or when at home and your parents don’t know what you’re looking at gives teens an additional layer of confidentiality and ease of use so that they can get information when they want it.”

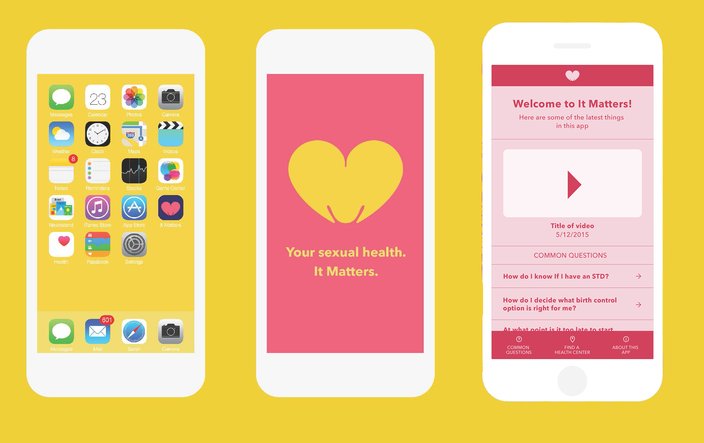

Called "It Matters," the app will release in December for iOS and Android. It includes a comprehensive guide for sexuality and STIs, a list of nearby resources and an open line of communication with trained health experts.

Mock-ups of the "It Matters" sex ed app, to release in Fall 2015. (Contributed Art / Access Matters)

But its mere existence begs the question: Why, in a city as progressive as Philadelphia, would youth need to turn for answers to their phones rather than their teachers?

The answer is as complicated as "the talk" itself.

The State of Sex Ed in Philadelphia

To understand sex ed in Philadelphia, it's vital to first understand sex ed in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania law does not actually mandate sex education; only a lesson on HIV prevention -- stressing the effectiveness of abstinence -- is required. Take a gander at the guidelines in other states, and Pennsylvania's approach to sex ed comes off as an indifferent shrug.

That kind of hands-off approach to sex ed is particularly alarming in the context of Philadelphia, which ranks No. 4 on a list of cities with the highest STD rates. As of June 2015, according to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, 19 percent of all gonorrhea diagnoses are among adolescents age 13-19, and 31 percent of chlamydia diagnoses. In 2012, the teen pregnancy rate in Philadelphia was 80 per 1,000 females ages 15-19, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Public Health.

So what is the minimum standard for sex ed in the School District of Philadelphia? It is frustratingly complicated.

On the surface, all is well. The district will provide 24 "priority schools" with added support and resources in the upcoming school year, including evaluation of teacher competency. Per state requirement, its overarching program emphasizes prevention methods for HIV and, according to high school Scope and Sequence recommendations, offers information on everything from STDs, to sexual orientation to contraceptive use. But when asked about specific policies and requirements for sexual education, the district only pointed PhillyVoice to its Health Scope and Sequence course outlines, explaining "topics vary from puberty and inappropriate touching to HIV/STD/teen pregnancy prevention."

Health teachers, the district added, are provided "with current strategies and interventions to make sure the information taught is comprehensive and provides students with strategies to help them make healthy and safe decisions."

But several sources involved with district health education told PhillyVoice its curriculum, in practice, varies in comprehensiveness by school.

A physical-ed and health teacher for a high school in the district, who asked to remain anonymous, told PhillyVoice while he makes an effort to teach as comprehensive a sex-ed program as possible, the curriculum is all his own. If he didn't take the extra initiative, he said, it's entirely possible that his students wouldn't get nearly as thorough an education as the district insists it offers.

- Related reads

- "Dating apps facing some blame for rise in STDs"

- "Teen HPV vaccine does not spur riskier sex"

- "Planned Parenthood rolls out STD testing apps"

In truth, the most consistent part of the district's sex-ed program doesn't come from the District at all but from Philadelphia's Public Health Department. It provides every district high school with what's largely considered a nationally unprecedented lecture-style assembly about disease rates that gives sexually active students a chance to test for STIs and promotes the city's ongoing TakeControlPhilly free condom campaign.

STD Control Program Manager Melinda Salmon told PhillyVoice that program has successfully reduced teen STI rates since 2011.

To its own credit, the cash-strapped district has sought to improve sex ed in its schools, not necessarily by fleshing out its own curriculum, but by bringing in the expertise of others. Over the years, it has compiled a list of district-approved external organizations with which schools may consult. These organizations often come in to work with students for free under federal grants and include touchstone health nonprofits like Mazzoni Center and Access Matters.

James Andrews, a health counselor who runs two Access Matters Health Resource Centers at Frankford High School and South Philadelphia High School, told PhillyVoice students frequently come to him with questions about pubic hair growth, condom use as STD prevention and how the menstrual cycle works.

The problem, he said, is students tend to have all of their sexual education crammed into one high school health course.

"Starting before high school would be a wonderful start," Andrews noted. "And having consistency in the School District and the state – each school is different in what’s addressed. So having something mandated, ‘This is what has to go into education,’ that would be helpful as well.”

Adrienne Ralston, an educator who's been brought in to teach classes as a consultant in district high schools and select middle schools, told PhillyVoice she's seen first-hand the misinformation spread in Philly's high schools in her 10 years there. It's a product of a district that's well-intended, she said, but hasn't prioritized its sex ed program in the way it should.

"Essentially, there is no program," she said outright. "Basically, what we're looking at is a patchwork system."

Ralston said teachers she's spoken with often want to teach comprehensive sex ed but are apprehensive. Aside from being overwhelmed with other priorities, they fear the pushback that could come from parents if they say something wrong. To volunteer to take on a comprehensive sex-ed program is a risky endeavor.

Ralston: We don’t teach kids how to drive after they get a license. It’s the same concept: You want to make sure that, for safety reasons, they’re going to be competent behind that wheel.

“I can’t say it enough: Schools want this. They know they need this," Ralston said. "And I really believe we’re not in a situation where teachers or admins don’t care about the kids and are just punching in."

Her suggestions echo Andrews': Youth need to be taught sex ed "before the ship sails," she said, in middle school, or even earlier. Philadelphia School District students, according to the 2013 Youth Risk Assessment Survey, are about twice as likely to have sex before the age of 13.

"Even if they’re not engaging in sexual activities, they still need to be getting the information," Ralston explained. "They should be getting it before they initiate sex."

"We don’t teach kids how to drive after they get a license. It’s the same concept: You want to make sure that, for safety reasons, they’re going to be competent behind that wheel."

What's next?

It goes without saying some schools have a sterling record of providing youth the knowledge and skills they need, and the school district can certainly only absorb so much of the blame for high STD and teen pregnancy rates when the state refuses to encourage basic sex ed standards. But change at the state level doesn't look likely anytime soon.

House Bill 1163, or the "Healthy Youth Act," was passed by the Pennsylvania House of Representatives Education Committee in 2010. It establishes minimum standards for sexual education that would teach medically accurate information on the transmission of STIs, pros and cons of contraceptive use and risk reduction. The bill also would ban the state from funding abstinence-only-until-marriage programs.

By 2013, though, the legislation was dead in the water. A representative for State Rep. James Roebuck, an officer for the current House Education Committee, told PhillyVoice priorities have shifted to safer schools following the Sandusky scandal at Penn State, not to mention a focus on evaluating the effectiveness of Keystone exams and general recovery from education cuts under Gov. Tom Corbett.

Nationally, politicians such as Sen. Claire McCaskill have introduced legislation that would require all high school sex-ed programs to introduce the subject of "safe relationship behavior," meant to curb sexual violence following a string of well-publicized campus assaults. The bill's fate is undetermined.

Local experts on human sexuality and sex education agree the lack of state-issued standards makes implementing comprehensive and consistent sex education difficult.

To its credit, state teachers have more leeway with their curriculums than in other states, Michelle Scarpulla, a professor of public health at Temple University, told PhillyVoice.

But, she added, "a big part of the problem is the state not having inclusive standards. [The state] buried its head in the sand and doesn’t want to make any determination."

Elicia Gonzalez, whose organization GALAEI also works with the school district, told PhillyVoice the city's sex-ed problem also points to a larger cultural issue of treating sex as taboo. What schools need to do first, she said, is acknowledge sexuality as a core piece of human development, a lifelong learning process and not just a chapter in a textbook.

“Sex ed is as integral to a student’s well-being as is reading, science and math," she said. "And if we truly want to have healthy and responsible youth and adults, then sexuality education – comprehensive sexuality education -- is critical.

"Sex ed can't just be an afterthought."