June 20, 2019

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Dr. Elisa Shipon-Blum, president of the Selective Mutism, Anxiety and Related Disorders Treatment Center in Jenkintown, has spent years researching and treating selective mutism, a social communication anxiety disorder.

Lisa Fosello first recognized that her son, Joseph, was acting differently than most children when he was in preschool.

Then three-and-a-half years old, Joseph played alone and would not speak to his teachers or his classmates, Fosello said. He never requested playdates. But inside the family's New Jersey home, Joseph was a chatterbox who appeared completely comfortable in his surroundings.

"It was just sad to see such a happy kid at home and then in social situations you could see him totally shut down," Fosello said. "He'd be like a butterfly at home and then he'd just go into his little cocoon when he was around people."

His family initially thought Joseph was simply shy, that he'd find his voice in time. Yet, by first grade, his social interactions had not improved.

It turned out that Joseph had selective mutism, a social communication anxiety disorder in which a child is unable to speak or communicate effectively in at least one social setting but comfortable in others. Often times, such children speak regularly at home, but have difficulty speaking at school or in other group settings.

The disorder affects about 1 in 140 children. But it is often misdiagnosed as shyness, autism or other intellectual disabilities. And many people, including the teachers and principals who interact with affected children, have never heard of it.

"One of the reasons kids are misdiagnosed with autism is that they can present as autistic within a social setting," said Dr. Elisa Shipon-Blum, president of the Selective Mutism Anxiety Research and Treatment Center in Jenkintown, Montgomery County. "They avoid eye contact. They shut down. They don't respond to people."

Many families spend years searching for the correct diagnosis and an effective treatment, Shipon-Blum said. But children can overcome their mutism.

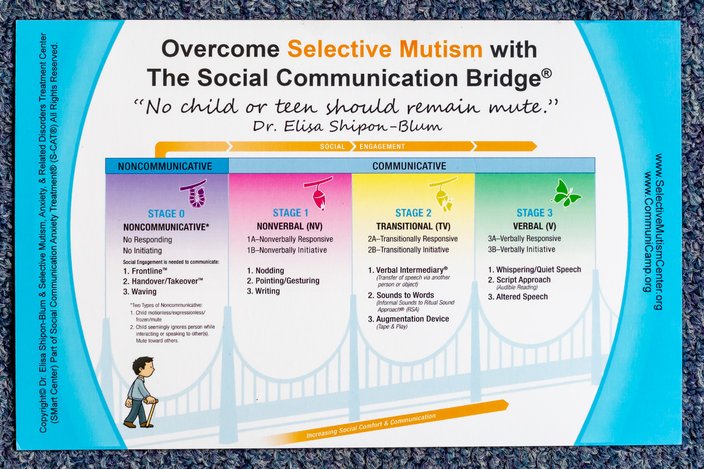

The SMart Center offers individualized intensive treatment programs designed to identify the underlying causes of selective mutism and place patients on a path forward. Using a treatment based in cognitive behavioral therapy and a family systems approach, patients gradually progress across four communication stages ranging from noncommunicative to verbal.

The SMart Center receives patients from across the world, including places as far as Singapore and the Philippines, Shipon-Blum said.

"We offer a tremendous amount of support, because most of these families feel very lost," Shipon-Blum said. "They're often the only one in their community that has a child like this."

Using cognitive behavioral therapy, Dr. Elisa Shipon-Blum guides patients with selective mutism across the four stages of communication outlined above.

Shipon-Blum – affectionately known as "Dr. E." to her patients – speaks from experience.

Her daughter, Sophia, received three different diagnoses, including severe autism, before being diagnosed with selective mutism as a young child. Sophia was so miserable that she would pretend to perform voice box operations on her stuffed animals. Today, she's pursuing her own medical career.

Spurred by Sophia's case of selective mutism, Shipon-Blum spent years researching the disorder and developing a treatment known as Social Communication Anxiety Treatment. She has written books, spoken at conferences and treated some 6,000 patients.

The key to overcoming the disorder, Shipon-Blum said, rests in identifying its underlying causes. They range from language abnormalities to social anxiety to sensory challenges. Abuse, neglect and trauma do not cause selective mutism.

"Most individuals think kids with SM are just very socially anxious," Shipon-Blum said. "Yes, there are kids that are – like my daughter. But there are kids that have these other issues and that's the missing piece. We need to figure out what those pieces are."

In addition to its individualized intensive treatment programs, the SMart Center runs a trio of three-day summer camps, dubbed CommuniCamp, designed to replicate a school setting where many of the children struggle to speak.

There, clinical staffers lay the groundwork for progression by introducing cognitive behavioral therapy techniques. Meanwhile, parents receive training so that they can implement these techniques outside the home. That's where the true work – and improvement – happens.

"She's just a completely different child. She said she was locked up in her own head. She feels free from that now." – Sara Carney, on her daughter, Chloe, 11

"You can't expect this child to go to a therapist, sit in the back room and then the parents leave," Shipon-Blum said. "This is a very hands-on type program. It's changing parent behavior, changing teacher behavior. Then children change. Just teaching parents how to reword questions to a child can elicit so much progress."

Each night, the families are given tasks to complete together, allowing the children to practice the coping skills they learned during the day. These tasks may include having the child order food at a restaurant or pay for an item at a store.

Parents are taught ways to prevent children from hiding behind them or hugging their leg during social interactions, a habit known as shadowing. They also are encouraged to speak directly to their children, avoiding instructions that begin with the phrase, "Can you."

Chloe Carney, diagnosed with selective mutism, once struggled to communicate with people outside of her family's home. Thanks to therapy at the SMart Center, she now feels comfortable speaking with schoolmates and teachers.

"What does that tell the child?" Shipon-Blum said. "It tells the child, I'm not so sure, sweetie, that you can do that. It's showing insecurity. We teach parents to speak directly – 'Honey, why don't you give that to Aunt Sally?'"

The camps, open to children ages 3 to 17, run $2,175 for most families and are considered out-of-network expenses with insurers. Any reimbursements are worked out between the families and their insurers.

For, Sara Carney and her daughter, Chloe, the camps proved invaluable.

"The patterns that selective mutism parents get into is that you just speak for your child," said Carney, of Charlotte, North Carolina. "You don't realize how much you're doing it until Dr. E is in your face saying, 'How do you handle this situation at stores and restaurants?'"

Like many parents, Carney found the SMart Center after an exhaustive search. Chloe was diagnosed at age 4 and bounced from therapist to therapist for several years. But Carney said they saw little improvement until the family attended a pair of Communicamps in 2017.

The first time, Chloe began whispering to some of her peers. But Carney said her big breakthrough came a few months later when she returned.

Now Chloe, 11, orders her own food at restaurants. And she freely talks to other children and her teachers.

"She's just a completely different child," Carney said. "She said she was locked up in her own head. She feels free from that now."

The Selective Mutism, Anxiety and Related Disorders Treatment Center works with young children as well as teens and adults. This is a workroom for children at the center.

Joseph Fosello's breakthrough came when he got home from Communicamp last summer. For the first time, he began talking to a landscaper that regularly came by his house. He did likewise with one of his mother's friends, a woman he had never directly addressed.

Joseph Fosello shows off the ribbon he earned for placing second in his school's spelling bee. Fosello was diagnosed with selective mutism, a social communication anxiety disorder in which a child struggles to speak in at least one social setting but remains comfortable in others. Through therapy at the SMart Center, Fosello has made considerable progress, his mother says.

"When I came home from camp, I was like, 'What do these people mean that this is going to change our lives?'" Lisa Fosello said. "Then slowly things started to happen that never happened before. He seemed a little more confident in front of people."

Like many children who attended Communicamp, Joseph, 10, continues to see Shipon-Blum for follow-up sessions. Fosello credited those sessions – and the various techniques implemented by the family – to Joseph's steady progression.

She received a welcome surprise on the first day of school last fall. Joseph's teacher called to say they had had an entire conversation about "Star Wars," science and the New York Yankees.

By December, Joseph was confident enough to participate in a school spelling bee in front of four classes of kids, Fosello said. He placed second.

"It was just heartwarming to see," Fosello said. "I cried at the spelling bee like a baby because it was so exciting. ... It fills your heart just knowing whatever you're doing at home and whatever Dr. E. is doing in that office is helping."

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy/Sara Carney

Courtesy/Sara Carney Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Courtesy/Lisa Fosello

Courtesy/Lisa Fosello