Scientists studying differences in bone marrow activity made an unexpected discovery about our heads – there are tiny tunnels running within the human skull.

- RELATED STORIES

- Biorhythms and birth control: FDA stirs debate by approving 'natural' app

- Lack of sleep could be as risky for your heart as smoking

- Penn research offers hope in fight against brain cancer that killed John McCain

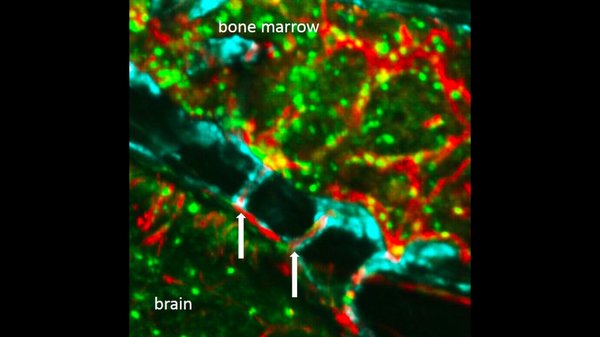

The tunnels – which connect skull bone marrow to the lining of the brain – may provide a critical shortcut for immune cells responding to brain injuries caused by stroke and other disorders.

"We always thought that immune cells from our arms and legs traveled via blood to damaged brain tissue," said Francesca Bosetti, program director for the National Institute of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. "These findings suggest that immune cells may instead be taking a shortcut to rapidly arrive at areas of inflammation."

Immune cells – produced by bone marrow – serve as the body's lifeline, fighting off infections and healing injured tissue.

Following a stroke, researchers found that the skull is more likely to supply immune cells to the inflamed brain tissue than the tibia – a large bone located in the lower leg. That differs during a heart attack, when the skull and tibia send similar amounts of immune cells to respond to damaged heart tissues.

This suggests that the injured brain and skull bone marrow may communicate in a manner that prompts a direct response, researchers found.

"We started examining the skull very carefully, looking at it from all angles, trying to figure out how (immune cells) are getting to the brain," said researcher Dr. Matthias Nahrendorf, a professor at Harvard Medical School. "Unexpectedly, we discovered tiny channels that connected the marrow directly with the outer lining of the brain."

Using advanced imaging techniques, they observed immune cells moving through the channels. Typically, blood flowed through the channels, moving from the skull's interior to the bone marrow.

But following a stroke, immune cells could be seen heading in the opposite direction toward the damaged tissue.

Researchers first discovered the tunnels by studying mice. But they later found similar channels when they examined human skull samples obtained from surgery. The human tunnels are five times larger in diameter.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Health and published in the journal "Nature Neuroscience."

Follow John & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @WriterJohnKopp | @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Add John's RSS feed to your feed reader

Have a news tip? Let us know.