October 05, 2023

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/PhillyVoice

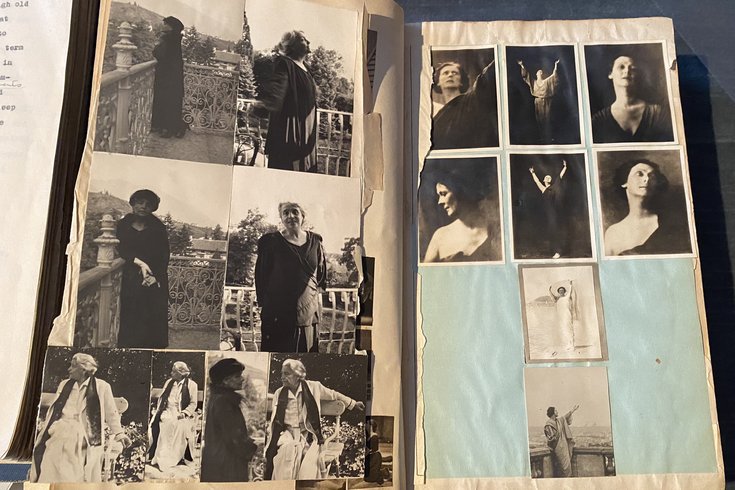

Rosenbach's collection of rare books and manuscripts includes the Mercedes de Acosta papers. The queer writer of 'Here Lies the Heart' was uncommonly open about her sexuality, and her family bible, shown here, includes photos and notes from the women in her life, including dancer Isadora Duncan.

Back in 1960, the writer Mercedes de Acosta sent shockwaves through Hollywood with her frank memoir "Here Lies the Heart."

Though hardly a steamy tell-all by modern standards, the autobiography detailed de Acosta's intimate relationships with 1930s movie stars like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich — even if she never outright calls them her girlfriends. With descriptions of private beach vacations, gifts of flowers and jewelry and feelings of intense longing, it was easy to read between the lines.

"One day in the lobby of the Pera Palace Hotel I saw one of the most hauntingly beautiful women I had ever beheld," she writes of Garbo. "Several times after this I saw her in the street. I was terribly troubled by her eyes and I longed to speak to her, but I did not have the courage."

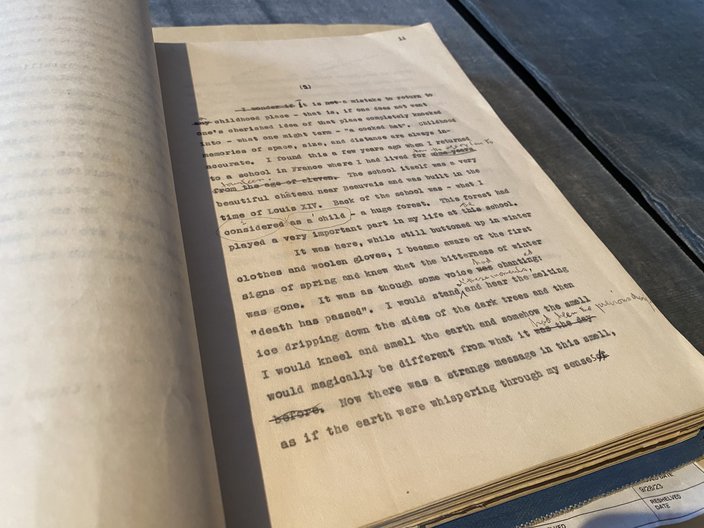

A proof of the book now resides in cabinets of the Rosenbach, the Center City museum and library near 20th and Delancey streets dedicated to the art of writing. Toward the end of her life, de Acosta sold her papers to the museum to pay for medical expenses, leaving behind various drafts, letters, telegrams and even her family bible. They now make up a part of the Rosenbach's extensive collection of over 400,000 rare books and manuscripts, many of which are rarely displayed in the building, the former 19th-century townhouse of the brothers and collectors Dr. A.S.W. and Philip Rosenbach. Many items, however, are accessible via appointment.

De Acosta may be an obscure figure today, but during her lifetime, she wrote numerous poems, plays and screenplays and belonged to artistic communities in both New York and Los Angeles. Born in 1893 to upper-crust Spanish immigrants, young Mercedes bucked convention even as a child, chaffing against the "the stiff, starch frock with the usual sash in pink or blue round my tiny waist, and uncomfortable leather pumps" she was expected to wear at formal parties, where she was "pulled about by some dreadful little boy who in most cases could not lead me as well as I could have led him."

According to biographer Hugh Vickers, she believed she was a boy, or maybe neither a boy nor a girl. As she grew older, she fell in love with dance, theater and the artists who performed them. She also joined the suffrage movement and chopped off her hair.

"Right from the start, I think she really embraced being different," Emilie Parker, director or education and interpretation for the Rosenbach, said. "Her attitude and her confidence and her just sort of way of being was something that was unusual and, as people thought, indicative of being a lesbian.

"She just embraced being herself, to her own detriment really in a lot of ways."

A proof of Mercedes de Acosta's memoir 'Here Lies the Heart.'

By her early 30s, de Acosta had published three volumes of poetry and penned multiple plays, including "Jacob Slovak," a drama about anti-Semitism that opened on Broadway in 1927 to some success. (The New York Times called it an "honest and interesting play.") But she soon relocated to Los Angeles to pursue a career in screenwriting. During her time on the West Coast, de Acosta did uncredited work on the 1932 movie "Rasputin and the Empress" and wrote several screenplays that were never produced, including a Clara Barton biopic called "Angel in Service."

Though she struggled to establish herself as a writer in Hollywood, de Acosta had no trouble building a thriving social life there. She befriended the renowned costume designer Cecil Beaton, who called her a "furious lesbian," and had several affairs with women while married to the painter Abram Poole. In "Here Lies the Heart," de Acosta claims she encouraged those women to adopt her androgynous style, leading Garbo and Dietrich to don trousers. In one photo from a 1935 issue of "Movie Mirror," Garbo and de Acosta walk down the street in complementary pairs of pants.

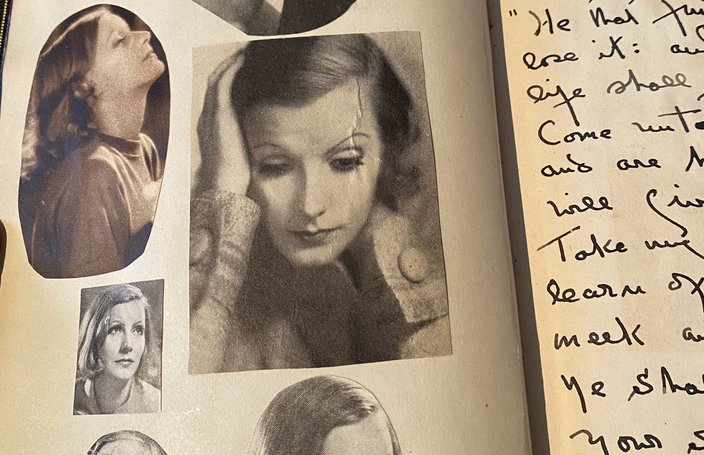

Some of those women are featured in de Acosta's family bible, which she treated more like a scrapbook, or a teenager's bedroom wall. Cut-out photos of Garbo and the dancer Isadora Duncan adorn the pages, along with handwritten notes, reflecting de Acosta's ambivalent attitude toward Catholicism.

The bible includes a page of Greta Garbo photos, apparently cut out from periodicals.

"Toward the end of her life, she was asked religion she subscribed to, if any," Parker said. "She was definitely born Catholic, but she said that if she had to choose, it would be Buddhism."

The Rosenbach's collection also includes de Acosta's correspondence with the celebrities she knew. Back in 2000, the museum received national attention as it prepared to unseal letters between Garbo and de Acosta, which the writer had stipulated could not be shared until 10 years after both women had died. The content wasn't especially intimate or interesting — likely due to Garbo's famously private nature — but messages from Dietrich are more revealing. In one telegram, the actress thanks de Acosta for filling her room with white roses, her favorite flower. "My room is a white dream," she writes. "It will be hard to leave Hollywood now that I know you."

Dietrich was unbothered by de Acosta's memoir when it hit bookshelves in 1960, but many other women described in the book were furious. Garbo cut off all contact with her, and her biographers would later paint de Acosta as a deranged stalker, which contributed to a perception that de Acosta was little more than an eccentric socialite. While her high class undoubtedly made it easier for her to be so open about her sexuality, Parker said, it also undercut her literary career.

"When she was socializing, she was doing it for a purpose," she said. "It wasn't just, you know, party girl antics. People really enjoyed talking with her as well, it wasn't as if she was just sort of feeding off people. You get the sense in her letters that people are kind of asking her advice, were fascinated by her just as much as she was fascinated by them."

Years of salacious gossip and fading memory have obscured the real de Acosta, Parker said, but flipping through the pages of her papers, readers will get to know the "really blunt, smart and best kind of intense person" curators at the Rosenbach have championed for decades.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice