June 12, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Ritzy Rittenhouse Square in Center City Philadelphia is best known for its 19th-century renaissance, when some of the wealthiest Americans built mansions along its borders. But its history also includes the likes of bricklayers, coal heavers and Irish servants.

More than any of William Penn's five original squares, Rittenhouse Square is synonymous with the neighborhood that developed around it.

Renowned for the surrounding architecture, beautiful landscaping and its prestigious associations, the square remains the jewel of one of Philadelphia's most fashionable neighborhoods.

On summer days, Rittenhouse Square is filled with residents relaxing on benches, shoppers strolling walkways and smokers sitting on its limestone balustrade. By December, holiday lights adorn its many trees.

Every year, the park hosts farmers markets, art shows and a spring festival. A flower show, held for more than a century, remains one of its signature events while a summer ball brings out the city's elite.

The square is best known for its 19th-century renaissance, when some of the wealthiest Americans built mansions along its borders. But its history also includes the likes of bricklayers, coal heavers and Irish servants.

Rittenhouse Square – so ritzy today – began with a working class vibe.

Originally known as Southwest Square, Rittenhouse Square not only stands unique for what it became, but also for what its early history lacks.

Unlike the other public squares, Rittenhouse Square never served as a burial ground. The public never flocked there for executions, as Philadelphia's early residents did at Logan Square. Nor did it witness horse races, like those held in Centre Square, now City Hall.

Instead, the square remained part of a forested area known as Governer's Woods until the days of the American Revolution.

Early settlers described the woods as a good place to hunt birds, foxes and deer. Benjamin Franklin was known to pass through them on his trips to John Bartram's estate on the banks of the Schuylkill River, a route that also required Franklin to use George Gray's ferry.

Governor's Woods were cleared prior to the British occupation of Philadelphia during the American Revolution. At that point, Rittenhouse Square became a grazing ground, not unlike the pastures surrounding it. In 1816, the city's councils passed a resolution to enclose the square, distinguishing it from the surrounding pastures and preventing livestock from wandering in.

With the heart of Philadelphia having developed along the Delaware River, many of the city's noisier and dirtier industries were pushed out to the areas surrounding Rittenhouse Square. There, a mixture of brickyards, lumberyards and manufacturers of pottery, glass and porcelain assembled.

"Because of its associations today with high-living, it's strange to learn that for much of its early history you were more likely to run into cattle or a coal heaver than a member of the leisure class," said Vincent Fraley, communications director for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. "The soil in Rittenhouse Square wasn't fertile enough for farming, but it turns out there were clay deposits. So, the first residents were bricklayers and other laborers that came and established kilns."

In the early 19th century, they were joined by poor, unskilled laborers who moved coal along the Schuylkill River that was shipped down the river from Schuylkill County.

A tight cluster of houses that developed along Manning Street – then known as Ann Street – was dubbed "Goosetown Village" due to the geese that flocked to the water-filled clay pits in the area.

By the mid-1830s, the streets surrounding Rittenhouse Square had been paved with cobblestone and lit by gas street lamps. A horse-drawn omnibus ran across the city on Market Street. Housing values west of Broad Street doubled, then tripled.

The area largely remained a working class neighborhood. But that was about to change.

Benjamin Franklin rightly receives considerable recognition as colonial America's preeminent inventor. But his accomplishments also cast a shadow over David Rittenhouse, a contemporary scientist with his own impressive achievements.

This portrait of David Rittenhouse was painted in 1795 by Charles Willson Peale. Rittenhouse began his career as a clockmaker but later served as an astronomer, mathematician and surveyor.

The self-educated Rittenhouse began his career as a clockmaker but transformed himself into an accomplished astronomer, mathematician and surveyor. In 1825, the city renamed Southwest Square after Rittenhouse in an effort to commemorate Philadelphia's storied colonial history.

As an astronomer, Rittenhouse helped observe the transit of Venus, a rare but predictable event in which Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, creating an eclipse-like effect. He also constructed a pair of orreries – mechanical devices that depict the orbits of spatial bodies.

As a surveyor, Rittenhouse established the boundaries between many mid-Atlantic states and surveyed canals and rivers using astronomical observations.

During the American Revolution, Rittenhouse served on the Committee of Safety, overseeing the improvements of rifles, the casting of cannons and selection of gunpowder mill sites.

He later served as Pennsylvania's treasurer, the director of the U.S. Mint and a trustee at the University of Pennsylvania.

A group of people assemble in Rittenhouse Square in April 1910, three years before the park was redesigned by Paul Philippe Cret.

Today, Rittenhouse Square refers as much to Philadelphia's ritziest neighborhood as it does the square itself.

But until the city's elite began building mansions along the square in the 1850s, the neighborhood had a less-than-rarefied name: Goosetown. And the square had experienced minimal renovations.

The square received its first real landscaping effort in the mid-1830s, when its clay pits and ponds were filled with soil. Saplings were planted and gravel walkways installed. A pair of streets were constructed along its western and southern edges, better defining its borders.

A second round of improvements came in 1853, just as the neighborhood began to see real change.

An iron fence, standing six-feet tall, was erected around the square. A trio of large, ornamental fountains was installed, though they were not beloved by all. They eventually were removed because they overflowed and the resulting mud dirtied trousers and skirts.

A series of benches and gas lamps were installed and the grass – which previously grew high – was cut with regularity. The park became a popular place for churchgoers to visit after services and for children to play as their parents watched from their mansions.

In the wintertime, some of the boys would get mischievous, said Nancy M. Heinzen, who detailed the square's history in her 2009 book, "The Perfect Square." On snowy days, they would sneak into the park and toss snowballs at passersby.

"The big trick was to knock top hats off with their snowballs," Heinzen said. "It's amazing how they grew up in that atmosphere."

Many of the Walnut Street mansions seen in this early 20th century photo of Rittenhouse Square are no longer there. But the fountain, originally used as a small wading pond, remains.

The park closed at dusk, when constables would close the swinging iron gates at its four corner entrances. Some boys would sneak into the park at night, according to Charles J. Cohen's "Rittenhouse Square: Past and Present," published in 1922.

"We boys used to gather at the Square after dark and climb over the fence, when the constabulary was not looking, and roam around inside, chiefly, I take it now, because we were doing something that we were not supposed to do," Frederick Shelton told Cohen. "We used to spot trees with sparrows' nests in the daytime, mark them, and at night go and gather them in."

The city removed the iron fence and replaced the thin, gravel paths with asphalt walkways in the mid-1880s. These changes came despite the opposition of many Rittenhouse residents, who feared their children would suffer bloodied knees and encounter runaway livestock originally destined for slaughter.

But their petition helped prevent the expansion of the streets around the square. And significant changes would not come to Rittenhouse Square until 1913, when the residents formed the Rittenhouse Square Improvement Association.

By that time, the square had fallen into disrepair. About 100 trees stood dead or dying. Dozens of shrubs were said to add little beauty. And there was a trash pit in the southeast corner.

The association tapped Paul Philippe Cret to redesign the park. A French-born architect who taught at the University of Pennsylvania, Cret later went on to design the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, Rodin Museum and the Memorial Arch at Valley Forge.

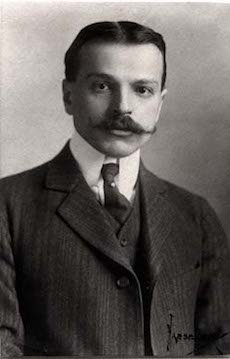

Paul Philippe Cret, shown in this portrait by Conrad Frederick Haeseler, was selected to redesign Rittenhouse Square in 1913. He later designed the Rodin Museum, the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and the Memorial Arch at Valley Forge.

Cret based his Beaux-Arts design on the Parc Monceau, a Parisian park. His plan called for diagonal crosswalks leading to an oval terrace at the park's center, which was enclosed by a limestone balustrade. The walkways were lined with trees and benches were placed toward the fountain, flower beds and statuary.

Since then, Rittenhouse Square's design has mostly remained unchanged.

At various times, residents have fought against changes, including a 1950s proposal to construct a parking garage beneath the square. Instead, the garage was constructed above ground, on the site of a former Walnut Street mansion.

Residents also successfully averted proposals to lay trolley tracks across the northwest corner, project that would have impacted about one-third of the square.

Instead, Rittenhouse Square remains far less impacted by traffic than Franklin, Logan and Washington squares.

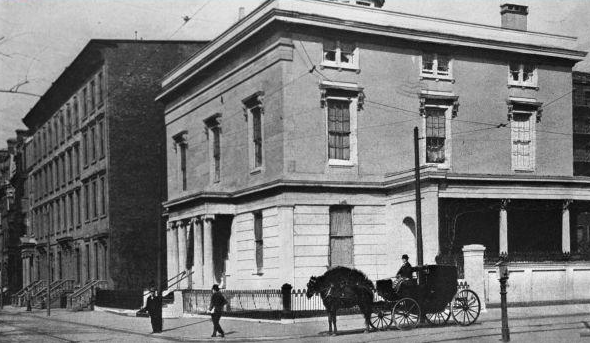

Philip Physick built the first mansion along Rittenhouse Square in the early 1840s. But Physick lost his inheritance in bad investments and never actually lived in the home, shown above in a photo taken around 1900.

The transformation of Rittenhouse Square from a working class neighborhood into a posh, self-contained neighborhood began to hit its stride in the 1850s, as a slew of mansions were built along the square.

Philip Physick was the first to construct a mansion along the square. In 1838, he bought five adjacent lots at 19th and Walnut streets, where he planned to build a Greek revival mansion.

But Physick, a lawyer who had inherited considerable wealth from his father, a celebrated surgeon, was not viewed as a visionary. Rather, his decision to put a mansion in an undeveloped area bordered by brickyards was deemed foolish by many contemporaries.

And Physick never spent a night in his own house.

"People became millionaires overnight. They decided they needed fancier houses."

The house took four years to construct and ran over-budget. In the meantime, Physick lost much of his inheritance in poor silk investments. He couldn't pay his creditors and his unfinished house was sold at a sheriff's sale in 1843.

But James Harper, a former congressman, had a better fortune.

Harper, a longtime owner of a brickyard near Rittenhouse, began building a home along Walnut Street in 1840. He also used a Greek Revival style, but built his home in the narrow fashion of Philly's rowhomes. That enabled Harper to sell his adjacent properties when the first upper-class residents began moving into the area in the 1850s.

The square offered wealthy Philadelphians a clean, relatively undeveloped area away from the city's booming industrial areas. Yet, it remained a short distance to Broad Street, which increasingly became a more important thoroughfare, and was connected to the rest of the city by a network of horse-drawn carriages.

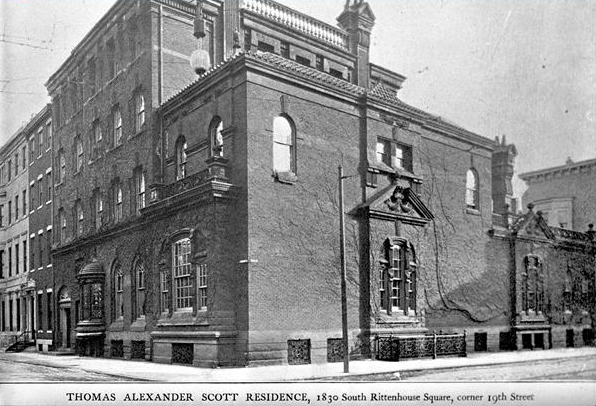

Beginning in the 1950s, Philadelphia's wealthiest residents began building mansions along Rittenhouse Square. Thomas Alexander Scott, a prominent railroad executive, owned a mansion at the corner of 19th Street and South Rittenhouse Square.

"Between the 1850s and 1890s, it became the place where, if you had the money and were going to have a Center City address, it was going to be there," Kenneth Finkel, a professor of American studies at Temple University, previously told PhillyVoice. "It might not be right on the square, but it would be within a stone's throw."

Among the first upper class families to move onto the square were those of businessman Henry Cohen and banker Francis M. Drexel. Their arrival helped establish Rittenhouse Square as the high society neighborhood it eventually became.

The Cohen family moved to the south side of Rittenhouse Square after reverberations from a freight train collision on Broad Street had caused their pantry shelves to collapse, destroying cherished chinaware.

Meanwhile, a trio of developing industries – coal, iron and the railroad – were increasing the wealth of some Philadelphians greatly.

"People became millionaires overnight," Heinzen said. "They decided they needed fancier houses."

Count Joseph Harrison, one of the wealthiest Americans, among them.

By the mid 1850s, Harrison decided to build a mansion modeled after Russia's Pavlovski Palace along the east side of Rittenhouse Square. Spanning an entire block, the mansion included a wing that housed a vast collection of art, which later became an integral part of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Harrison, a poor native of Kensington, had designed a locomotive engine that caught the attention of a visiting Russian trade group, which asked him to construct a railroad between Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Instead of receiving a flat fee, Harrison negotiated a contract that awarded him royalties for every individual transported on the line. When the Crimean War erupted, and Russia began transporting thousands of soldiers on the railroad, Harrison became a rich man.

After gaining a fortune by building a railroad between Moscow and St. Petersburg, Joseph Harrison constructed an elaborate mansion that nearly spanned an entire block along Rittenhouse Square. The mansion is pictured here in 1866.

Rittenhouse Square was on its way to becoming the poshest neighborhood in Philadelphia. By the turn of the century, it was populated with elegant mansions, offices, churches, upscale boutiques and social clubs.

"That's its first real estate renaissance," Fraley said. "That's when you have Wanamakers and Lippincotts and what Nathaniel Burt – a historian I really like – called the Perennial Philadelphians. That's when they moved in and it became what it was."

Yet, such lavish lifestyles demanded "presumptions of superiority, the exercise of assured authority and the collaboration of a servant class," Dennis Clark wrote in "The Irish Relations: Trials of an Immigrant Tradition." The rich depended upon servants to serve meals, wash clothing and clean the house, among other chores.

Many of these servants hailed from South Philly's Irish enclaves. More than a third of the city's 24,000 servants were born in Ireland, according to the 1870 United States census. And another sizable portion had been born to Irish parents.

"The working people who served were often from such impoverished backgrounds that they had no choice but to serve, and some may even have been beguiled into servility by the mere thought of association with the elegance which they labored to support," Clark wrote.

The construction of The Church of the Holy Trinity, the neighborhood's first Episcopalian church, signified the changing demographics of Rittenhouse Square. Built in 1857 across from the square's northwest corner, the church catered to the WASPy elites moving in.

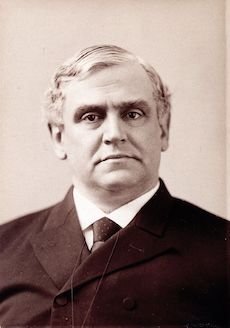

Phillips Brooks, a rector at The Church of the Holy Trinity on Rittenhouse Square, penned the words to 'Oh Little Town of Bethlehem' after returning to Philadelphia from a visit to the Holy Land.

Previous churches, like Saint Patrick's Church, had served the working class community that initially developed near the square. But as the upper class moved west, numerous churches popped up in the neighborhood over the next several decades.

Many of the churches remain active today, including Holy Trinity, which holds a bit of history.

Its second rector, Phillips Brooks, preached against slavery from the pulpit during the Civil War. His abolitionist views prompted some to leave the church, but he remained popular, often preaching to overflowing crowds.

Following the Civil War, Brooks went on sabbatical to visit the Holy Land, including Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus. Upon his return, he wrote the lyrics to "Oh Little Town of Bethlehem." The church organist, Lewis Redner, set the words to music, and the popular Christmas carol was born.

Redner wrote the music quickly, after Brooks urged him to complete the tune just two days prior to a Sunday morning practice, according to Louis FitzGerald Benson's "Studies of Familiar Hymns," published in 1903.

"I thought more about my Sunday-school lesson than I did about the music. But I was roused from sleep late in the night hearing an angel-strain whispering in my ear, and seizing a piece of music paper I jotted down the treble of the tune as we now have it, and on Sunday morning before going to church I filled in the harmony. Neither Mr. Brooks nor I ever thought the carol or the music to it would live beyond that Christmas of 1868."

The historic facade of the Rittenhouse Club, a social organization once populated by Philadelphia's elite, now fronts one of the many apartment buildings constructed along Rittenhouse Square.

As Rittenhouse Square attracted more and more wealthy residents, a plethora of social clubs developed in the neighborhood.

The Union League, founded to support the policies of Abraham Lincoln, was the first to move within a short walk of Rittenhouse Square, building its mansion on South Broad Street in the 1865.

The Social Art Club followed in 1878, rebranding itself as the Rittenhouse Club due to its location inside James Harper's mansion on north side of Rittenhouse Square. In 1902, the popular club joined Harper's mansion with a neighboring building, erecting the beloved Beaux Arts facade that now fronts a high-rise condominium.

Like many of the other clubs that popped up, the Rittenhouse club served as a place where businessmen, intellectuals and other elites could gather for conversation, hear lectures and enjoy musical performances. Businessmen could drop into the clubs as they headed home from work.

Other clubs, including the Penn, Four-In-Hand and Print clubs formed in the decades before and after the turn of the century.

The Racquet Club, featured in the 1993 film "Philadelphia," included Jay Gould, a world champion tennis player and gold medalist. Its founder, businessman George D. Widener, perished aboard the RMS Titanic in 1912.

Many of the clubs strictly catered to Christian men. But The Acorn Club, founded in 1889, became the country's first women's club. And the Locust Club was founded in 1920 by Jewish businessmen who could not gain admittance to other clubs.

Some of the clubs, like the Union League and Acorn Club, continue to operate. But others, like the Locust Club, have closed over the years due to declining membership.

Rittenhouse Square, viewed from the AKA Hotel at 18th and Walnut streets, show the park's northeast entrance and the surrounding high-rise buildings.

Residential changes again hit Rittenhouse Square in the early 20th century.

This time, the neighborhood developed upward as the city's elite headed outward.

The first high-rise apartment complex rose up in 1913, replacing the Scott family mansion on South Rittenhouse Square. Built by Samuel Wetherill, the high-rise signified a changing dynamic.

"In a way, Rittenhouse Square didn't have to retain its old sensibilities. But it did. Barely, but you do get the sense of it...." – Kenneth Finkel, Temple University professor of American studies

The city's elite steadily began moving to the suburbs, where many of them had built summer homes in the countryside. The Pennsylvania Railroad's main line provided access, but the newly-adopted income tax provided another incentive.

It became cost-prohibitive to maintain mansions in both Rittenhouse and the suburbs, Heinzen said. But many people opted to also maintain an apartment in the city.

"This was just an alternative way to live for rich people," Heinzen said. "The Barclay Hotel was built as a resident hotel. The idea of apartment living is very European."

Many other apartment complexes followed. The Wellington, Rittenhouse Plaza and 1900 Rittenhouse all went up in the 1920s. High-end hotels, like the Warwick and Drake, also opened.

But as these buildings took shape, many of the mansions that formerly lined the square were demolished.

"They were lovely mansions," Heinzen said. "Very few exist."

By the 1950s, many of the mansions that once lined Rittenhouse Square had been torn down in favor of the high-rise apartment complexes that now make up the square's landscape.

Harrison's expansive mansion, on the east side of Rittenhouse Square, was torn down in 1920 to make room for the Pennsylvania Athletic Club.

Some mansions were preserved by cultural institutions, like the prestigious Curtis Institute of Music and the Philadelphia City Institute, which both still occupy spots on the square. Social clubs moved into others.

The Great Depression halted development on the square until the Rittenhouse Claridge was built in the 1950s. The Lippincott mansion, built in 1866, was torn down to build 220 W. Rittenhouse Square, a 32-story high-rise that sparked concerns about increased shadows over the square.

Another apartment boom would follow in the 1960s. By then, many of the older high-rise apartments had become an accepted part of the architectural landscape.

"In a way, Rittenhouse Square didn't have to retain its old sensibilities," Finkel said. "But it did. Barely, but you do get the sense of it. ... These buildings could have all been like New York, demolished and rebuilt as towers and the feel would be entirely gone."

Instead, the prestige of Rittenhouse Square continues to this day.

Source/Public Domain

Source/Public Domain Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Photo courtesy/Historical Society of Philadelphia

Photo courtesy/Historical Society of Philadelphia Source/Public Domain

Source/Public Domain Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/Public Domain

Source/Public Domain Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org