April 25, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

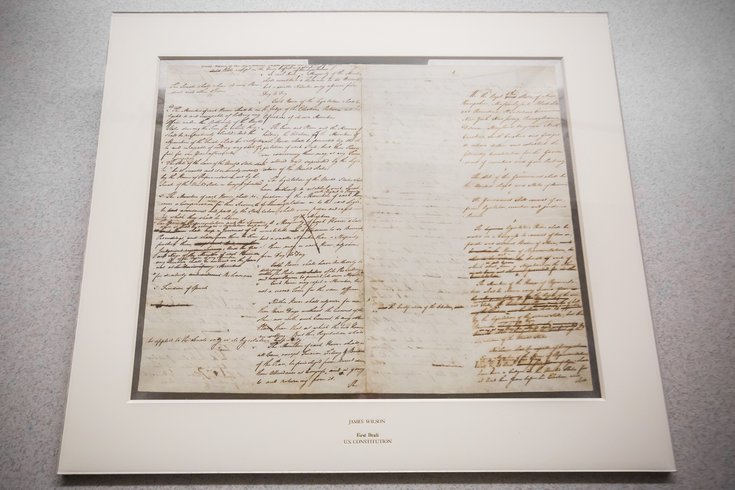

The first draft of the U.S. Constitution was handwritten by James Wilson, a Pennsylvania delegate from Carlisle. Since the ink contains bits of metal, it has begun to rust and turn brown. Originally, the ink would have appeared black. The document is owned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The seminal moment at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 bridged the divide between the big and small states by establishing the bicameral legislature structure still in place today.

The so-called Connecticut Compromise remains a central lesson of American history classes. But it may not stand as the most critical moment to the U.S. Constitution's actual development.

Early, handwritten drafts of the Constitution suggest the most innovative and replicated characteristics of the document were developed by a five-person committee tasked with drafting the details of the broader structures debated on the convention floor.

Those drafts — and the story they tell — will go on display together for the first time at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia when it opens its new exhibit gallery on May 4 through a partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, which has housed the documents for more than a century.

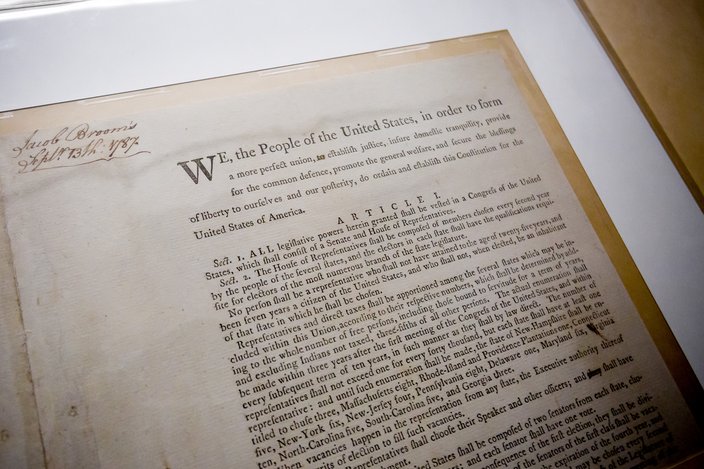

The exhibit, dubbed "American Treasures: Documenting the Nation's Founding," will feature the first two drafts of the Constitution, both handwritten by Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson, who later became a Supreme Court justice. A copy of the third draft — the first to be printed and distributed among the delegates — also will be on display.

"...Much of what the Constitution is came from this committee. You can't see it without these drafts. They don't exist anywhere else, except right here." – Charles T. Cullen, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The exhibit stands to inform even the most accomplished constitution scholar, HSP interim President Charles T. Cullen said.

"We think of Madison as the Father of the Constitution – and I don't take that away from him," said Cullen, a longtime legal historian. "He pushed it through and really shepherded the whole process after it went to the floor. But a lot of what ended up in the final (version) came from these five people. And you can tell that from looking at a lot of the emendations."

The first handwritten draft references the "United People and States of America" and lists each of the original 13 states within the preamble. Had that opening stuck, generations of high school students would have had a mouthful to memorize. Instead, the preamble is a more succinct 52 words.

But the documents also reveal the origins of developments far more consequential to American government.

The first attempts at specifying the enumeration of congressional powers, outlining federal judicial power and drafting the necessary and proper clause fell to the Committee of Detail — not the convention as a whole.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceLee Arnold, senior director of collections at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, uncovers the first printed draft of the U.S. Constitution. It is stored in the most secure area of the organization's archives.

In analyzing the early drafts for its July 2011 edition, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography suggested historians have overemphasized the Connecticut Compromise and understated the importance of the Committee of Detail.

The Connecticut Compromise has not produced substantive litigation or been widely copied by other constitutions, the magazine noted. That stands in contrast to "the distinguishing features central to the American system," like the overlapping of federal and state legislative powers, the tripartite structure of the federal government and the system of judicial review, the magazine said:

"The vote of July 16 is indeed fundamental to the history of the convention: otherwise the proceedings might have collapsed. But it not equally important to the history of the Constitution. If our interest is in understanding what the convention accomplished – what it contributed within the broad sweep of Western constitutional history – then the work of the Committee of Detail is of fundamental importance."

But by the time Wilson's handwritten drafts were discovered in the late 19th century, the narrative surrounding the Constitution's development, and the importance of the Connecticut Compromise, had been formed by historians.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania acquired the drafts when Emily Hollingsworth donated the paperwork of her grandfather, James Wilson, to the organization in the late 1870s. Hollingsworth does not appear to have known what the paperwork contained.

The Wilson papers, which also included his accounts of the Committee of Detail's work, sat mostly ignored for another two decades. Therefore, much of the work conducted by the Committee of Detail went unrecognized.

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoiceThe first printed draft of the U.S. Constitution was printed by Jacob Broom and distributed to each of the delegates attending the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

"When you read the drafts and note what they started with and what they then produced for the convention to debate, you see that much of what the Constitution is came from this committee," Cullen said. "You can't see it without these drafts. They don't exist anywhere else, except right here. That's what makes them so rare."

The historical society is partnering with the Constitution Center in an effort to promote the myriad treasures its houses — some 20 million documents, including a copy of the Articles of Confederation.

Wilson's handwritten drafts of the Constitution have never been placed on display together. But they'll kickstart an array of historical documents that HSP will place on display at the Constitution Center's new gallery for the next 10 years.

Eventually, the display could include documents highlighting women's suffrage or Prohibition, Cullen said.

"It calls attention to the National Constitution Center's commitment to be a center where people come and study the Constitution, both its origin and its meaning," Cullen said. "And it calls attention to the fact that here, in Philadephia, is a place that has tons of materials that people can use to study more, if they want to.

"We want people to use the historical society to become engaged with us, as we are becoming engaged with the rest of the city."