March 20, 2017

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

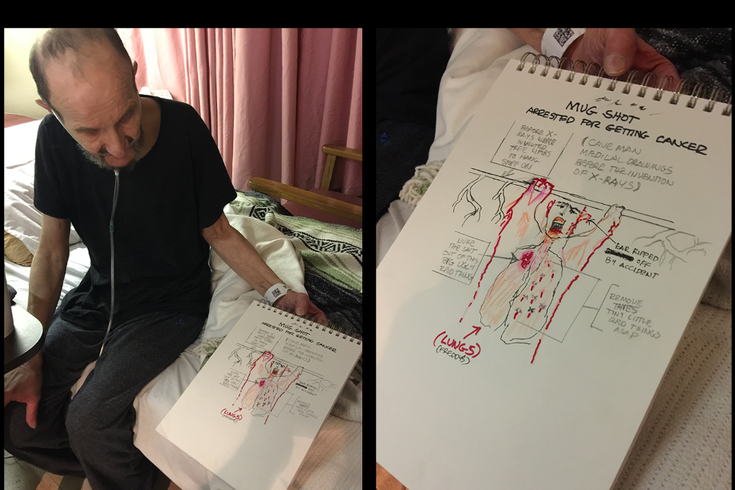

On a Sunday when his friends were hosting a fundraiser across town, local punk-rock legend Freddy Pompeii reflected on life and his ongoing battle against lung cancer. He's currently being treated at a University City hospice facility.

Seven months ago, a doctor told Freddy Pompeii that he had nine months to live. That was the worst-case scenario. Surviving a year? That was the best case.

Freddy’s the type of guy who’s been outrunning stuff throughout his 70 years of life, though. That characteristic doesn’t bode too well for the lung cancer he’s fighting at the Penn Center for Rehabilitation and Care in University City.

Sure, he cried and contemplated that news when he received it last August. Then, he got to work cheering himself up, something made easier when he bought into the second opinion that told him “not so fast.”

Let’s not start that morbid countdown quite yet, a second doctor told him. There’s a chance that 34 rounds of radiation could help. There’s a chance that the next summer he sees won’t be his last. There’s a chance he could beat this thing.

That's what keeps his spirits up these tough days of being confined to a hospital, which is better than the once-recommended hospice alternative.

Pompeii wasn’t Freddy’s surname at birth. He was known as Freddy DiPasquale while growing up in South and Southwest Philadelphia. It wasn’t until he got to Canada in the late 1970s that he took a new stage name.

You see, Freddy is a punk rocker.

To those steeped in the genre, he’s something of a legend.

“When they gave me a death sentence, that’s when we were really upset about it." – Freddy Pompeii

And while his local fame never matched his notoriety in Toronto as a recognizable face of “The Viletones,” friends, family and fans in both cities – some he hadn't seen in decades – have banded together to help Freddy battle his latest foe by turning out at fundraising concerts.

It bolsters Freddy, knowing that people have so flooded the University City center’s front desk, the staff often asks whether visitors are “here to see Freddy?” before they announce that they’re there to see Freddy.

It’s inevitable that when you talk to Freddy, he’ll mention a future that sees him return to the stage someday.

It is, simply put, the never-wavering confidence of a rock star.

Even by South Philly standards, Freddy Pompeii is a unique character.

He has a mischievous grin, an irrepressible sense of humor, a creative soul, a passion and talent for most musical genres, a kind spirit, a tiny frame, a scratchy voice and quite a story to tell.

“Pardon me, man. I didn’t put my teeth in this morning” is how he started his story from his hospital bed back in February.

It was a Sunday morning. Later that day, friends both local and from afar would gather at a South Philly bar to raise money to help cover his medical expenses.

The person of honor couldn’t attend, which bummed him out.

“It’s breaking my heart, man. I wanna be out there with them,” he said, while accepting the reasons why he couldn't leave.

Instead, he laid out his life story as episodes of “The Walking Dead” blared from his bedside television.

Sporting a Ramones T-shirt with pink Chuck Taylors on the floor nearby and a table loaded with markers and pencils for drawing and writing purposes, he apologized for the volume.

The chemo “compromised” his hearing. His easygoing roommate never kicked up a fuss about volume, which is nice. When he’s not drawing or writing, Freddy needs people to talk loudly so he can hear them.

He grew up the lone boy in an eight-child family. They moved from South Philly to Grays Ferry in his early years. “Employment opportunities” for the adults is how he explained it.

His dad was an undefeated, 115-pound amateur boxer.

“He knew he could kill you with a punch,” Freddy said. “Think before you speak. That’s how I was raised.”

“You know that saying ‘they don’t look for trouble, it finds them’? That’s his business card." – Rodney Anonymous

When World War II arrived, his dad served and his mom’s biceps grew from Rosie the Riveter-like shifts at the factories in Southwest Philly.

Freddy always had an artistic streak. He was into folk music and the tracks Jerry Blavat was spinning.

At the same time, that creative side didn’t stop him from “learning how to defend yourself in the streets” thanks to the South Philly vs. West Philly gang fights at the 69th Street terminal.

Freddy’s dad was also a commercial artist. His son followed those footsteps, drawing and designing ads for a number of area newspapers after graduating from West Catholic High School and Hussian College School of Art in Society Hill.

Music was always his first love, though. His first band of more outfits than he can count on one hand, Abridged Version, “had a silly name.” That, and another band, wouldn’t last more than two years. Both tried to sound like other bands instead of pursuing the unique sound he wanted.

“I was starting to come up with something original and Philly wasn’t open to that. There was no punk scene here,” he said through coughing fits. “I was disillusioned.”

So, off to Canada he went where the “f***ing music scene really knocked my socks off.”

He soon met Margaret Barnes DeColle there. She would become his wife. Then, she became his ex-wife. And then, after the cancer diagnosis, Margaret transformed into Freddy’s caretaker. She was by his side after the diagnosis and she is by his side regularly to this day.

In 1972 or 1973 – he’s not exactly sure – he bought an amp and an electric guitar, started honing a unique sound and “finding people in my headspace.” A little band called Rush – “they were kids to me” – helped change things up north. People were talking about the Toronto scene outside of Toronto before long.

“Only a handful of people were open to making original music. (Venues) wanted original, but only if it sounded like The Band or The Beatles,” he recalled. “I needed to find people like me.”

One such person – Steven Leckie “with a NY Dolls look” who he saw at “big shows that you wouldn’t see in Philly” – fit that bill. He found other compatriots by placing newspaper classified ads around the time The Ramones played there.

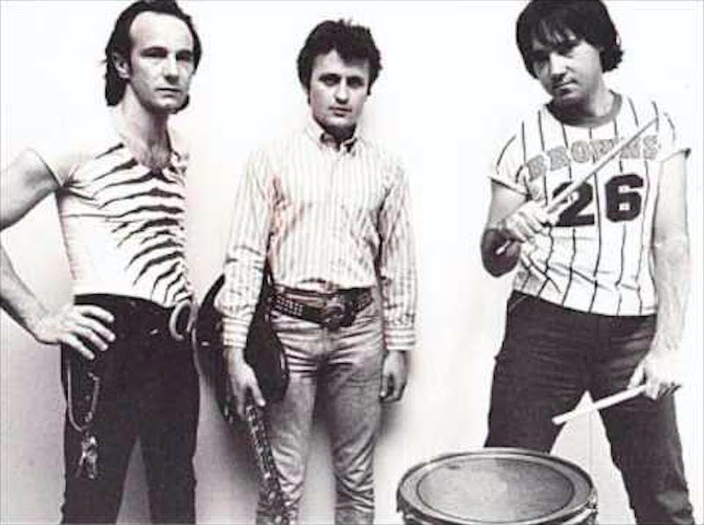

Before long, The Viletones – with Freddy on guitar, Leckie with vocals, Motor X on drums and Chris Hate on bass – were born and the path toward punk stardom formed.

His bandmates' penchant for “too much goofing off” led him to quit the band, but that changed when they showed up with a case of beer, banging on the front door, saying they nailed down a two-night gig.

“When do we start playing?” was one question.

“When do we start seeing the world?” was another.

“We don’t do either unless we rehearse and get a lot better than we are,” was Freddy’s answer to both.

“When you’re on the middle of it, you never think you’re good,” Freddy recalled of those long-ago days. “We were not ready yet. But, it all happened so fast.”

That gig was at a place called The Colonial. The upstairs venue was for the top acts. The downstairs venue was where promoters tried to get upstarts some stage time. The Viletones got the latter.

“When we got there, the line was around the block. I thought, ‘What the f***? Is there another band on the bill tonight?’” he said. “’That’s for us, man. They all came to see us.’ That’s what they said to me. I didn’t believe them. Well, the f***ing place was packed beyond capacity.”

The next day brought a big newspaper article. The headline read “Not Them, Not Here.” It was tongue-in-cheek. The review called them “the worst band and the best band in the world at the same time.”

It was their big break, and it led to gigs at CBGB’s in New York City for “Canadian Weekend” in 1977.

“We were bad boys,” he explained.

By the time the band returned to Toronto, they had offers from wannabe managers and record deals. They would be the subject of a skit on "SCTV," Canada’s version of "Saturday Night Live."

“It was a right-place, right-time thing,” he said. “We were rolling. We were knocking people out of their f***ing socks.”

They’d knock people out of their socks, but only for a couple years.

Two years later, they all got into some trouble. The way Freddy tells it – cryptically – some of them took a trip to Ottawa. Unbeknownst to him, there was a drug dealer in the mix. There was a set-up.

“Everybody got in trouble, including me,” he said. “In 1979, I moved back to Philadelphia. Nobody was telling me that the charges got dropped. I didn’t think I was allowed to go back. I’ve only taken two trips up there since.”

The Viletones were no more, at least not in the iteration that included Freddy Pompeii, who would retreat into quasi-anonymity in South Philly.

In one sense, Freddy returned to local anonymity while retaining his punk edge by traveling to New York City for rehearsals and shows with other acts. (Those trips always took a little longer since he couldn’t drive through New Jersey courtesy of a “driving without a license” issue in the past.)

He did so while retaining that commercial-art professional life.

“When we came back to Philly, he was working a straight job. Sometimes, that gets in the way of being a punk rocker,” Margaret told PhillyVoice this week. “When he formed bands with people in New York, he was always traveling up there, spending a lot of time rehearsing. That’s why he’s not as well-known around here.”

Right up until his diagnosis in 2016, he was writing for – and performing with acts called “Thee Immaculate Hearts” and “Fight, F*** Fight or Dance.” There was even a Viletones reunion a year or so back.

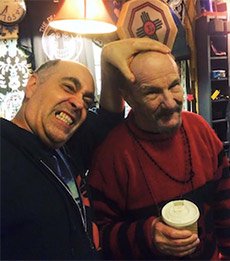

Rodney Anonymous, keft, and Freddy Pompeii

While he first met Freddy in South Philly about five years ago, “it feels like I’ve always known him.”

“I’m a big fan of any band he’s been in,” Rodney said, noting that through a friendship with his wife Vienna, Freddy ended up at one of their house parties. “We instantly clicked. Any music I had on, he picked something great out of it. Even if it was new music, he was interested.”

But there’s more to Freddy than musical acumen.

“If you’re around him, something interesting will always happen,” he said. “You know that saying ‘they don’t look for trouble, it finds them’? That’s his business card. Weird crap always happens around him.”

Then came that August day when his landlord – a Penn Medicine nurse home on maternity leave – saw him struggling to get up stairs at his spot near 49th and Warrington.

“Fred,” she said, “you don’t look good.”

“Well, it’s just the heat,” he thought. “It was going on for a while, the problems with the stairs. I had to catch my breath every flight.”

“No, you look really bad today,” she responded, before driving him to the hospital.

“They got me into a room really quickly. I was in there for two hours, doing tests, X-rays, that kind of thing,” he recalled. “Then, the doctor came back and said I had cancer, just like that.

“I was by myself. I just sat there, contemplating that. I called Margaret immediately and told her. She’s been helping me ever since. That was the beginning of it. It took me two or three days to get over the crying spells and the ‘F***, what am I gonna do?’ mindset.”

There were tumors in his lung. It was not a good diagnosis in the least, and he put his artistic talents to work to draw a sketch with the phrase “nuke the s**t out of this one.”

Margaret Barnes DeColle and Freddy Pompeii meet actor Dan Ackroyd at a local wine-and-spirits shop.

That diagnosis was originally accompanied by the 9-to-12-month life expectation. A couple weeks later, his primary oncologist said they wanted to try radiation, the same treatment path that left his throat “sunburned” to this day.

“When they gave me a death sentence, that’s when we were really upset about it,” he said. “Two weeks later, it completely changed again. She was saying it’s treatable, that it wasn’t terminal, and she had the final say.

“Not saying you’re going to die in nine months? Well, that’s good news. That’s giving me some hope right there that there might actually be a future, that I can beat it.”

The musical career has to wait, though.

“Yeah, this has put the brakes on everything for a while,” he said.

So, what is it like for a punk rocker to face mortality for himself and others?

“It’s not the end of the world for you,” said Freddy of friends who are “really upset” and “shattered” about his current state of affairs.

The underlying premise is that it could be the end of the world for him, but only if he lets himself dwell on it in such a fashion.

At our second interview about a month after the first, Freddy donned an Iggy and the Stooges concert T-shirt. The TV was off and his breathing tube was looped over the hand-sanitizer dispenser near the door as he cleaned up after spilling water all over himself and his hospital bed.

After a break from radiation that had taken his toll, he would soon be heading over to the hospital for his treatment session.

When friends visit Freddy Pompeii at the hospital in University City, they lift his spirits and he lifts theirs.

Reading cards like the one that said “Freddy, you are immortal, young and beautiful forever” helps lift his spirits, as does hearing that the benefit concerts were absolutely packed with people who loved him.

“I think the treatment’s working. I don’t feel pain where I felt pain before, where they were trying to zap the cancer out of me,” said Freddy, who hopes he recovers to the point of getting a new project – a band called “Those Troublemakers” – up and running. “Do I physically feel better? No, I don’t feel better at all. Just to do the little things like drinking coffee or changing clothes knocks me out.”

Friends, that’s what makes it more bearable. Fans of The Viletones, The Secrets (which came afterwards) and his other bands, they help too.

There are relatives he hadn’t seen in years flying in from California for three-day visits.

There are bands he’s never heard of showing up to say hi at the facility, to get autographs on album covers.

There’s family (like Margaret) and friends like Anonymous and Dana Michael, who sang in Freddy’s “Fight F*** or Dance” group always checking in.

“Most hospital visits are depressing, but not with him,” Anonymous said. “We were over there on Christmas. There were families there, but they seemed like they were there out of duty. Well, we were there to get picked up by Freddy.

“(A friend named) John Howie got him to tell a dirty story at the top of his lungs. God help anybody who doesn’t know this dude. Part of you doesn’t want to go see a friend in the hospital, but I don’t think you can dim Freddy’s spirit. No amount of chemo can slow that down. This guy should be a role model for everyone. He’s an artist no matter what. If I get a cold, I’m down for the count. But, this isn’t going to get in the way for Freddy. He’s probably seen a lot worse than this.”

Dana Michael is one of those friends who Freddy thinks took the news as hard – if not harder – than he did.

They met through Anonymous. Michael is a self-described “itty bitty thing” which is what made Freddy’s “you should really eat a sandwich” line right off the bat all the more entertaining.

“(My husband) John was excited to meet a punk rock icon. When we first started chatting, he told me he was looking to restart his old band, that he was looking for a singer,” she said.

Anonymous then mentioned that Michael – with a background in musical theater, jazz and blues – was that singer. A band was born.

“When I started singing with Freddy, it gave me back my voice. I gained that with his friendship,” she said. “He’s a partner in crime, a confidant. He’s so funny. Every Thanksgiving, he spends with my family. My best friend is 70 years old. He reminds me what it’s like to have life inside me.”

Sure, the Freddy she sees today during hospital visits is the same Freddy from the stage. There are dirty jokes, like the time she asked “whether the nurses are giving happy endings.”

“I’m not ready to lose him, and he’s not ready to go yet." – Dana Michael

“I want to sleep there with him, but they won’t let me. Some days are harder than others. He has better days when people call, message or visit,” she said. “I’m not ready to lose him, and he’s not ready to go yet. It’s cool that he’s an icon, but he’s also just an amazing man.”

Margaret, who met Freddy when she was just 18 years old but has been divorced from him “for decades,” agreed with that assessment.

“Even when I go there, we don’t have to talk that much. We know how he feels,” she said. “I told him from Day One that this is going to be hard, that you have to take it one day at a time, that you don’t know what the next day’s going to be like, to live each day as fully as you can.

“When he gets up and starts telling stories, the room is filled with people laughing. That’s the best medicine.”

She said the benefit concerts – they raised some $11,000 for Freddy’s medical care – did lift his spirits noticeably. At the Philly show, attendees filled out Valentine’s Day cards from one of those kids’ packs. He was watching via Facebook Live and from pictures that people sent him from the show.

“He was so moved by it,” Margaret said. “He said later that ‘I just didn’t know that I was so loved.’ What a revelation. It’s not over till it’s over. It changed the whole way he saw his cancer and how he wanted to fight it. After those two fundraisers, after all the talk about radiation and chemo and being put in hospice, he said, ‘No, you’re not putting me out to pasture.’”

Sitting in his hospital bed in late February while awaiting his return to radiation treatments, Freddy reflected on his life, career and this latest wrinkle of realizing how widely loved he is by people who maybe didn’t take the time to say so all that regularly.

His response is a case study in the benefit of having people by your side when facing extreme challenges, even if you’re a punk rocker.

“That’s what makes it bearable. Everybody is being so positive about it, saying get well, we miss your performances, we want to see you perform again, to hear some new music from you,” he said. “Wanting to perform again, that’s the driving force.

“I never say ‘if’ I perform again. It’s always ‘when' I’ll perform again.”

Photo courtesy/Freddy Pompeii

Photo courtesy/Freddy Pompeii Photo courtesy/Dana Michael

Photo courtesy/Dana Michael Photo courtesy/Dana Michael

Photo courtesy/Dana Michael