If you've ever looked at pictures of yourself just after you were born and laughed at the shape of your head, there's now research confirming just how much the birth canal left a mark.

The human pelvis isn't built as well as those of other mammals to accommodate the size of our heads. Scientists have long known that fetal skulls can adapt during labor because the bones haven't fully fused together, but new research from PLOS One sought to better understand the mechanics of this process.

In a recently published study, researchers took MRI scans of seven women when they were between 36 and 39 weeks pregnant. Another MRI was taken when each woman was undergoing labor and her cervix was fully dilated.

- RELATED ARTICLES

- How traumatic injury has become a healthcare crisis

- These low carb tortillas are made with a vegetable you probably haven't heard of

- This nonprofit graded the nutritional value of Philly public school menus

The results showed that the degree of fetal head molding may be more significant than previously thought.

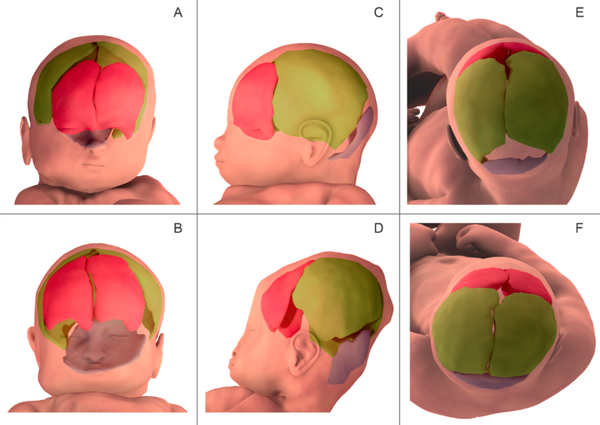

All seven of the fetuses displayed overlapping skull bones that did not visibly appear that way before labor. The pressure deformed both the newborns' skulls and the brains.

Five of the newborns' heads returned to their pre-labor cranial form shortly after birth. Two of the infants maintained what researchers called a characteristic "sugarloaf" skull, possibly due to differing elasticities of the skull bones and supporting fibrous structures.

The study, which raises new questions about what is considered a "normal birth," could allow scientists to develop realistic simulations of delivery in the future. These virtual trials of labor could help detect and prevent biomechanical risks related to childbirth.