May 06, 2019

Graham Beards/via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Graham Beards/via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

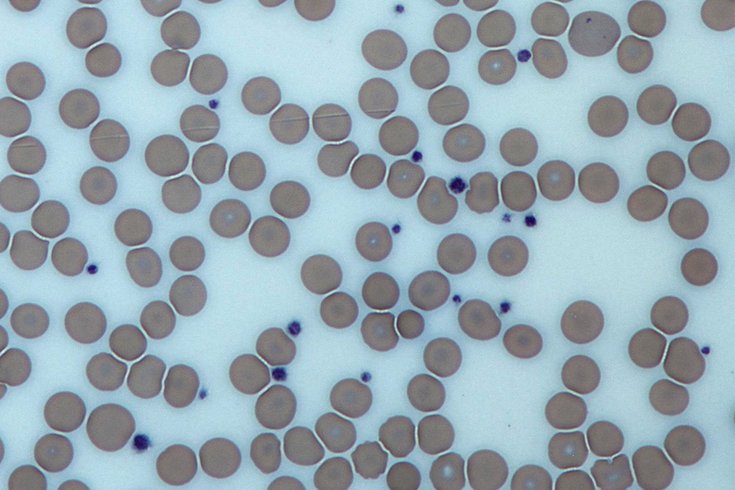

This image from a light microscope (magnified 500 times) shows platelets (blue dots) surrounded by red blood cells (pink circular structures) in a Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smear.

Have you ever been in a classroom and wondered to yourself whether the information being presented could be wrong?

During graduate school, I audited a medical school class in which the professor remarked that at some point in the students’ medical training, a fact would be presented that later may be shown to be incorrect.

New discoveries are continuously upending our most fundamentally held dogmas. One area currently being reexamined is the complicated interactions between the components of blood with your body. Don’t worry; just like your high school textbook says, red blood cells still bring oxygen from the lungs to rest of the body, and white blood cells are still protecting your body from foreign invaders. However, the more subtle roles of blood, especially in diseases like cancer, are not fully understood.

I am a cell and molecular biologist, and my background in research began with studying changes within cells that cause cancer. My interest in cancer eventually led me to explore how tumors are supplied with adequate nutrition. One blood component continued to arise in literature, displaying an interesting and dynamic role after a person develops cancer: platelets.

Platelets are the component of blood that springs into action when you get a paper cut or scrape your knee. The signals governing the recognition of a wound, and how to address healing, are quite complicated. However, under normal physiological conditions, these signals mediate a process called platelet activation, which results in healing the wound by closing broken blood vessels.

In addition to this well-known role, scientists have uncovered many other functions of platelets. In fact, an association between higher numbers of platelets and the progression of cancer has been recognized for nearly five decades. Platelet numbers are elevated in cancer patients, and studies have shown that platelet-mediated blood clots are associated with tumor cell metastasis.

That suggests that platelets may be linked to the spread of cancer to other parts of the body. But that may not be the only thing the platelets do for cancer.

Platelets, along with other cell types, release microparticles which respond to a variety of stimuli, including those which mediate platelet activation for wound healing.

While the mechanisms of microparticles are not completely understood, several studies have demonstrated they contain molecules that modulate which genes are turned on and off. Altering gene activity ultimately affects the production or turnover of proteins, which can cause a multitude of changes that affect health. Interestingly, microparticles contain molecules that have been shown to alter gene expression, and are associated with cancer progression.

That brings up an interesting question: Is it possible that platelets and the microparticles they release upon activation could also modulate cancer progression?

My colleagues and I sought to address this, beginning with perhaps the most important question: whether platelet-derived microparticles were detectable in patient cancer tissue. Indeed, using a high-resolution microscope we observed microparticles in cancers from many tissue types.

Importantly, we did not see microparticles in normal tissue from the same patient, indicating they were specifically targeting cancer cells.

This was a particularly interesting observation, because until then, these vesicle-like structures were hypothesized to affect only other cells within the blood vessel, and not target any other surrounding cells. Our team demonstrated that platelet-derived microparticles specifically target tumors.

Moreover, those targeted cells absorbed the gene-regulating molecules within the microparticles. However, contrary to our original hypothesis, we observed that microparticles inhibited solid tumor growth. This finding showed that platelets may not be so easy to pick on as only a bad guy in cancer progression.

New information has enabled researchers like myself to reevaluate our understanding of the role of platelets in cancer. Until recently, relatively few studies have observed a protective role of platelets in cancer.

While there is substantial evidence linking intact platelets to promoting cancer, the dual pro- and anti-cancerous roles of platelets raise some fascinating questions about both intact platelets and the microparticles that they release.

In this way, it is tempting to consider platelets as so-called chameleons within the realm of cancer biology. The intact platelets appear to promote cancer progression, but the microparticles do the opposite, creating a natural check-and-balance system.

Further, the so-called leaky nature of tumor blood vessels has been posited as a likely reason for microparticles to have access to cancerous, but not normal, tissue. It is enticing to consider that someday, with a bit more characterization regarding the cargo being transferred, scientists could utilize the body’s natural delivery of extracellular vesicles, like these microparticles, as a therapeutic resource.![]()

James Michael, Lecturer of Biochemistry, Thomas Jefferson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.