July 19, 2016

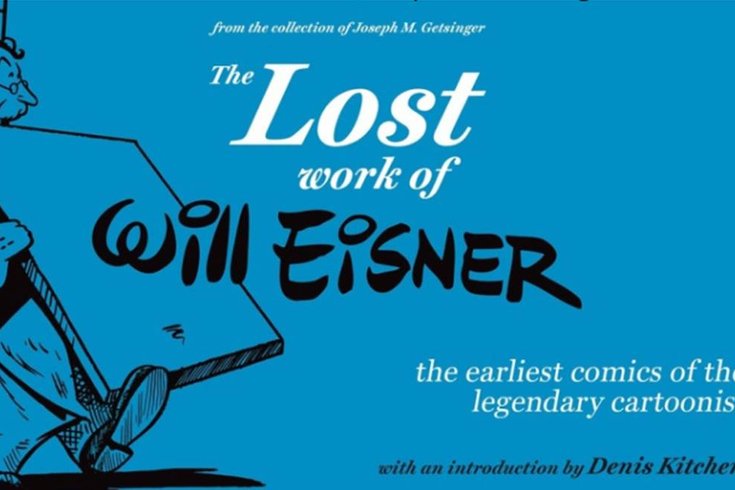

Photo courtesy/Locust Moon Press

Photo courtesy/Locust Moon Press

The Lost Work of Will Eisner," featuring the cartoonist's early work, will be available in September.

New Jersey artist Joe Getsinger discovered the lost art of comic book legend Will Eisner during an annual poker game.

Every year, a bunch of artists and publishers get together, make merry, and bring something to share. At the card table one of his friends passed around an old printing plate — kind of an enormous stamp used to ink cartoons — and part of a larger collection he’d recently come into. After inspecting one of them, Getsinger told his friend there could be something of serious value in the collection.

“I called him back maybe a week later and said, ‘You might want to hold on to these things,’” Getsinger said. “He’s always trading things off. He’s a barter nut, he’d barter sticks for rocks just for the sake of bartering. I said before you do that with these, you may have a diamond in the rough.”

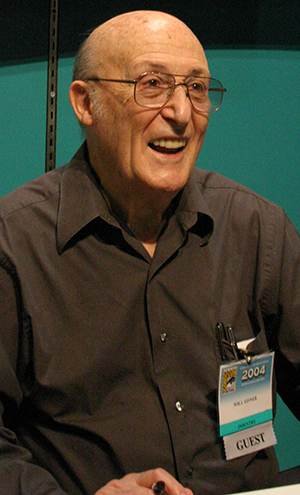

Will Eisner appeared at the 2004 San Diego Comic Con.

For those who aren’t well-versed in the history of comic books, Eisner's name may not be familiar. But he was one of the original greats, getting involved in the industry soon after the creation of Superman and Batman and creating his own more modest crime fighter, "The Spirit," who distinguishes himself by being more of an ordinary detective than a caped crusader (no expensive gadgets, just a small mask over his eyes and a standard-issue men’s suit).

Even in the 1940s his work seemed more sophisticated than that of his cape-drawing peers, and that promise flowered in the decades that followed. Eisner became one of the rare first-generation comic book artists who continued to be influential into the 1970s, when he basically invented graphic novels. 1978’s "A Contract With God," a set of interlocking stories based in a Bronx tenement, is arguably the first in the medium, and Eisner kept on cranking them out until January 2005, when he died at the age of 87. Today the most prestigious awards in the comics industry are named after Eisner.

The works that Getsinger discovered are from Eisner's lost, early years. The artist created "The Spirit" in 1940, but it turns out that beforehand he honed his skills as a cartoonist on everything from bizarre stuff about a derby-hatted schlub named Uncle Otto, to a straight-faced spy tale about a highly skilled operative named ZX-5. (Eisner wasn’t as good at naming his secret agent as Ian Fleming).

A West Philadelphia publisher will release a compilation of the newly discovered works.

“The comics we are publishing are very raw,” said Josh O’Neill of Locust Moon Press. “I mean he’s just a kid, but you can see him throwing all of this stuff and the kitchen sunk in there. He’s starting to figure out how to make these mega plots that would he would [execute with greater skill] in 'The Spirit' comics in the 1940s.”

The Locust Moon collection includes the hoary humor of Uncle Otto, a bizarrely apportioned working man who rarely speaks and basically serves as a springboard for a series of physical gags. Another comedic comic follows, featuring a Tintin-like boy detective named Harry Karry.

The comic plates containing the newly-found early works of Will Eisner. New Jersey collector and artist Joseph Getsinger discovered the strips.

Both strips demonstrate that Eisner was wise to turn toward serious crime and realist, almost autobiographical, comics for the rest of his career. Perhaps it’s the author’s young age, or the gulf that separates 1930s-era humor from that of today, but the jokes often don’t land. Most painful are a few very crude depictions of black people, like something out of the blackface "Amos 'n' Andy" show of that era.

The latter third of the book is taken up with the adventures of ZX-5, a suave secret agent who is hunting a nest of spies in his home country. The tone has markedly shifted, from the adolescent humor of the earliest works to an attempt at a suspenseful spy thriller with a gruesomely high body count. And as in "The Spirit," death and wounds are not easily shrugged off as they are in Batman or Superman (or James Bond for that matter).

In short, Locust Moon is offering insight into the birth of a genius before he could be characterized as such. The last of the ZX-5 stories are published in 1939, the year of Batman’s invention, and a year before Eisner’s own masked hero debuted.

“He first became famous was the very early '40s, when he first created 'The Spirit,' ” said O’Neill. “It was very forward-looking in a lot of ways, just brilliant cartooning, doing things with pacing no one had ever done before. The depth of characterization, these serial stories that went on for years.”

Locust Moon is itself the recent winner of multiple Eisner awards, but it nonetheless remains a scrappy indie press. It funded a hardcover printing of this previously unpublished Eisner collection via Kickstarter last November and met the $20,000 goal in less than three days. (They went on to raise $51,376 from hundreds of fans.)

The books arrived at Locust Moon Press this month and will go on sale in bricks-and-mortar stores in September. Due to the esoteric nature of the subject, its unlikely to be blockbuster. But perhaps sales will pick up if someone in Hollywood, having exhausted their stores of Marvel heroes, decides to try their hand at some of those original serialized arcs that Eisner scripted back in the 1940s, with a degree of sophistication that Superman and Batman were then unable to deliver. (The only attempt at a feature movie adaptation of "The Spirit" flopped, but it was a hyper-violent departure from the source material.)

“He was at the forefront of almost the entire history of the medium, throughout he was right there figuring it out,” said O’Neill.

Eisner gifted us with the complex, long-running serialization that came to dominate the comic book form, even up through the Marvel movies of today. It is the universes inspired by his work that have come to dominate our pop culture across mediums. But Eisner’s properties never quite got there. Even as he influenced the medium he never had the sales to match. In a way, then, it’s only fitting that this cache of his early work is being printed by a little publisher in Philadelphia.

Patty Mooney, Crystal Pyramid Productions/via Wikipedia

Patty Mooney, Crystal Pyramid Productions/via Wikipedia Photo courtesy/Locust Moon Comics/Kickstarter

Photo courtesy/Locust Moon Comics/Kickstarter