January 18, 2023

Analytics at Wharton/YouTube

Analytics at Wharton/YouTube

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society's Philadelphia LandCare program partners with the University of Pennsylvania on research into the effects of greening vacant city lots. A recent analysis found that homes surrounding these lots saw increases in property values.

A long-running program to clean up vacant lots in Philadelphia neighborhoods resulted in increased property values for homes within 1,000 feet of those formerly unkempt lots, according to research from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

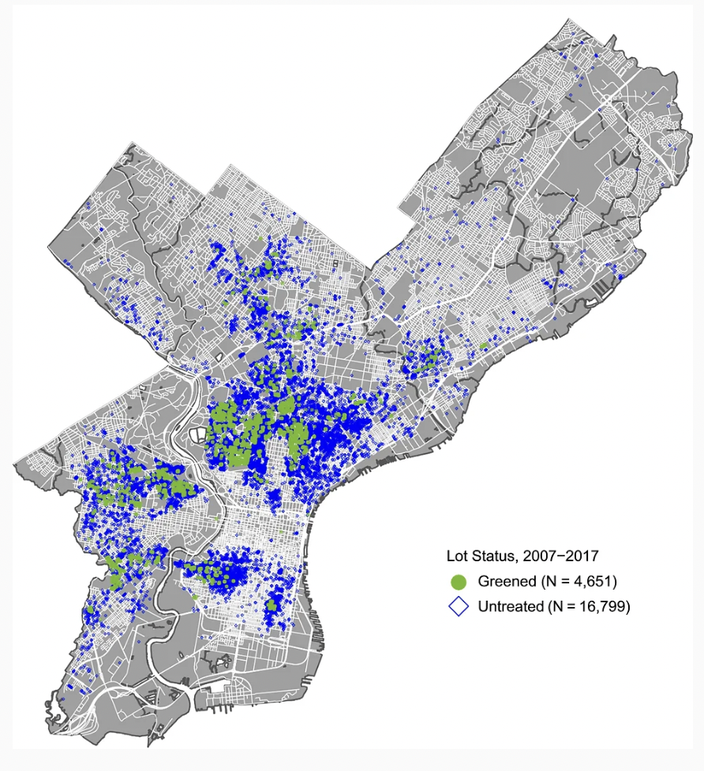

The study examined vacant lots in the city between 2007-2017, comparing 4,651 lots that had been greened to a control group of 16,799 lots that were left untreated during that period. The restored lots were improved through the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society's Philadelphia LandCare program, which was formed in 2004 to turn abandoned parcels of land into manicured, community micro-parks.

Compared to the control group, the lots that were greened pushed up the property values of nearby homes by an average of 4.3% after the first year. Within six years, homes within the 1,000-foot radius increased in value by a cumulative average of 13%. Approximately 18 homes fit within the range of a greened lot, with a median value of $250,000.

In the first year after a lot was greened, the surrounding homes together combined for an average increase of $193,500 in value.

The study, published in the journal Real Estate Economics, was led by Wharton professors Susan Wachter and Shane Jenson, with contributions from former student Desen Lin.

Research on the effects of greening vacant lots and repairing homes in Philadelphia has produced a number of findings on the benefits of such programs over the years. These block-level interventions have been linked to a reduction in violent crime in the surrounding area, a decrease in illegal dumping and lower rates of depression among residents.

The Wharton study found that the property value effects of greening lots varied by neighborhood, with greater increases seen in parts of the city with high shares of vacant land and higher-than-average median household incomes. In some areas, the surrounding property values saw peak increases of as much as 19%.

"This particular vacant lot greening initiative provides us with a really nice, almost experimental situation for evaluating what impact small changes in a neighborhood can have on various types of neighborhood outcomes,” said Jensen, a professor of statistics and data science. “Susan and I got involved specifically…because we were interested in real estate value and the potential change in housing prices that can be impacted by greening lots.”

Jenson explained that it was a challenge to come up with comparison lots for the study because there are many other factors beyond the status of vacant lots that influence property values. That includes population density, access to public transportation and other economic features of neighborhoods. The statistical methodology for the study used weighted linear regression modeling to help measure variables against one another.

A map of the lots that were analyzed for the study shows that the vast majority of lots that were greened in that timeframe are in North Philadelphia and West Philadelphia, with a smaller number of lots in South Philadelphia.

The map above shows lots used for the Wharton analysis between 2007-2017.

The Wharton team acknowledged that the prevalence of vacant lots in poorer neighborhoods might lead some to believe the PHS initiative's impact on property values could be a sign of gentrification. The authors argue that the property value increases only reach a small number of homes around each greened lot, and that the rises in property values are not pervasive enough to result in displacement of residents. That does not preclude other neighborhood real estate activity that results in displacement, but it suggests the greening of vacant lots independently offers tangible community and economic benefits to residents who live near these projects.

On average, greening lots through the Philadelphia LandCare program costs about $1,500 up front and $300 in annual maintenance for each lot. The intervention is relatively cost-effective compared to the value it generates.

“The reality is quite intuitive,” Matt Rader, PHS president and a Wharton graduate, said of the program. “If you think about living next to or walking past a lot that’s unmaintained, dumped on, filled with weeds, versus one that is clean, green, fenced and welcoming to you, it’s a major difference. It really transforms community life.”

The Wharton researchers and representatives from PHS will host a free-to-attend Zoom event this Friday, Jan. 20 at noon to discuss their findings on the effects of greening vacant city lots.

Source/Wharton School

Source/Wharton School