May 16, 2017

Photo by/Roderick Aichinger

Photo by/Roderick Aichinger

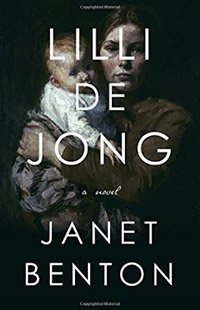

Janet Benton's debut novel, 'Lilli de Jong,' is a stunning look at the life of one 19th century Quaker woman fighting to survive as an unwed mother. The Philadelphia writer's book was released Tuesday.

In Trump-era America, literature must be more important than ever. Classic dystopian tales seem most urgent. Trumpian doublespeak, such as “alternative facts” and “involuntary immigrants,” begs us to re-read Orwell’s 1984. The breathtaking new Hulu television series, The Handmaid’s Tale, based off Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel of the same name, depicts a not-so-future world where the United States government has been overthrown by a theocratic regime that brutally subjugates women to be abused and bred as livestock. Many have noted the story hits disturbingly close to home .

But it is just as important for feminists and allies to read new historical fiction. As 2017 resurrects political scandals the size and scope of Watergate, we clearly see that history repeats itself. Still, it takes a talented novelist to persuade us to revisit our oppressive past.

Janet Benton is that novelist. The Philadelphia writer’s debut novel, Lilli de Jong (released Tuesday by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday), is a stunning look at the life of one 19th century Quaker woman fighting to survive as an unwed mother in a world that views unwed mothers as sinfully subhuman.

Benton’s protagonist, Lilli, seems to enjoy a relatively privileged upbringing, for a young girl living in Germantown, circa 1883. Her mother is a pillar in the family’s Quaker Friends community and her father is a talented furniture maker whose work is highly coveted. But a freak accident changes all that: Lilli’s mother dies a grueling death; her father impiously marries his cousin, and the entire family, including Lilli and her brother Peter, are severed from their church and its vital social network.

Barred from teaching at the church school and without any other career options, Lilli is trapped in her father’s house with his spiteful wife and flirtatious assistant, Johan, to whom Lilli clings through grief. When Johan proposes and promises her a life in prosperous Pittsburgh, Lilli risks consummating the relationship before Johan leaves with Peter to establish himself out west. Johan promises to send for Lilli, but he never does. By the sixth month of her unexpected pregnancy, she has no choice but to enter a strict, penitential home for unwed mothers, where she is expected to give birth and surrender her infant for adoption. Lilli’s decision to keep her daughter instead leaves them both at the mercy of a rigid self-righteous society with little mercy to spare.

The cover of 'Lilli de Jong,' which is out Tuesday.

I caught up with Janet Benton about the 12 years she spent researching and writing the novel, based closely on Philadelphia’s archives and landmarks, and what she hopes readers will take away about motherhood and women’s fundamental rights.

PV: What kind of research went into assuming the voice of a 19th century Quaker woman?

JB: Lilli’s voice came from a mix of influences. My own natural writing voice was one. Also influential were the voices of heroines in novels set in the 1800s that I adore, especially the voices of heroines Jane Eyre and Mary Reilly. I mean for Lilli de Jong to follow in the tradition of these great Victorian heroines and other classic novels named after their heroines, including Emma, Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina, Pamela, and Clarissa.

As for Quaker speech, I studied materials from the 1880s and earlier, as

well as contemporary works about that time, including books by and about

Quakers, diary excerpts, articles in Friends’ publications, and the

Discipline (a code of conduct that governs Friends’ Meetings). Lilli’s way

of using what Quakers call plain speech, such as her use of “thee” and

“thy,” and her ways of describing spiritual matters, are based on this

reading and on crucial advice given to me by Quaker historians.

PV: How does this historical novel about women’s lack of reproductive rights/parental autonomy inform modern American women’s fight for reproductive rights, health care, equal pay, maternity leave, etc.?

JB: I was raised by a feminist artist, read feminist works from middle school on, and traveled widely when young. So the novel is informed by my lifelong learning and experiences of women’s compromised human rights in the past and today.

Women’s inequality and the lack of support for mothering are profoundly embedded in societies around the world. They are chronic wounds. We have to take the blinders off. One of my intentions in this novel is to denormalize these wounds and the oppression of women—to make people feel deeply what it can mean to be a woman and a mother in unjust circumstances.

The unwed mother has long been a target. I hope my novel will help to make its readers understand better what it costs to do the incredibly hard and fundamental work of mothering. Women need to have real choices and need real, not sentimental, support in creating and raising children, if this is what they want to do. I’m not a politician; I’m a fiction writer. So I’ve aimed to move people toward greater understanding and compassion with a story.

PV: The novel touches on young women’s desperate, often gruesome attempts to terminate unwanted pregnancies. Do you think people today are out of touch with this part of women’s history?

JB: Lilli de Jong is set in 1883, when—because of an act of the U.S. Congress in 1873 (known as the Comstock laws)—it was illegal to deliver by mail or other means any material or information related to abortion, birth control, and the prevention of venereal disease. And abortion itself was illegal, which meant it was done without women being protected from huge fees, malpractice, and murder. This created further suffering and catastrophe for countless people. Many people still lack information and choices in their reproductive lives today, in the United States and around the world, and this causes unnecessary and profound suffering, poverty, and death.

PV: How did you research the fictionalized Philadelphia Haven for Women and Infants? How did it affect you emotionally to learn of these women’s struggles?

JB: I went to the Pennsylvania Hospital’s archives, which holds many valuable records of the State Hospital for Women and Infants, which is the institution on which the Haven is based.

I was deeply moved to read writings by the founders of this institution about the condition of the girls and young women who sought admission and protection there, as well as about the extreme difficulties they had getting donations to keep the place running. They wrote that even murderers “with malice aforethought” were shown more pity and assistance than young girls who may have been raped or at worst were naïve enough to fail to understand that they could become pregnant and betrayed by a man.

PV: How has your experience of Philadelphia been enriched by digging extensively into its past?

JB: I love the city more, knowing some of the history I learned from researching for the novel as well as from co-writing and editing historical documentaries for The Great Experiment, a series produced by Sam Katz of History Making Productions, which airs on 6ABC. I grew up in New England, but the Philadelphia area is my adopted home. I find it fascinating. Its Quaker roots and history of Quaker activism are among the features that distinguish it from other major U.S. cities; another is the survival of so many historic buildings, parks, and other sites.

I do get chills when I’m in parts of the city where Lilli and her baby, Charlotte, spent time, including the areas around City Hall, Rittenhouse Square, east Chestnut Street, the banks of the Schuylkill, south of South Street (east and west), much of Germantown, West Philadelphia (where the city hospital and almshouse used to be), and Washington Square. I find it easy to imagine the city in the nineteenth century while walking through it today.

Source/www.amazon.com

Source/www.amazon.com