March 31, 2016

Every year since 2009, the Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative has released a State of the City report on the changing fortunes of the city. On the odd years, a big sweeping 80-page status update is issued. But 2016 is an off year so the scope of this year’s research is more limited.

Nonetheless there are several important takeaways for the discerning reader in this year’s State of the City report, which was released Thursday afternoon. Here are the five big takeaways about the future of Philadelphia from the report.

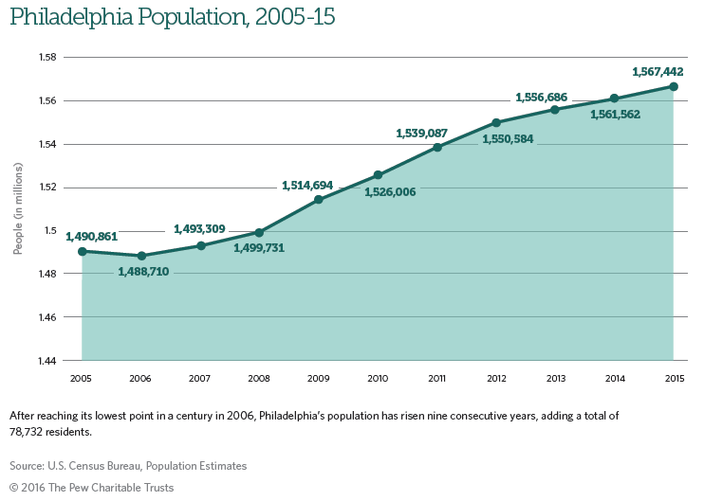

The city grew by 5,880 people last year, a 0.4 percent increase over the year before, and the ninth straight year of population growth. That’s certainly a great improvement on the previous half century of population loss, where the city bleed population to the suburbs, and the metropolitan region lost population to faster growing economies in the Southeast and the West.

But as welcome as any population growth is within that larger context, it should be noted that these additions to Philadelphia’s strength are very minor in terms of raw numbers. They are most impressive when measured against other Rust Belt central cities, like Cleveland and Pittsburgh, which have continued to shrink. But Philadelphia’s growth is substantially less impressive when compared with our rivals in the Sunbelt.

Philadelphians were gravely disappointed when Phoenix briefly surpassed our city as the fifth most populous in the nation at the end of the last decade. Our closest competitor was humbled shortly thereafter because its economy proved highly vulnerable to the depredations of the Great Recession.

But this year’s numbers seem to indicate that we should prepare to be disappointed again soon. Arizona’s Maricopa County, which includes, Phoenix grew by 77,925 people last year. That’s more than Philadelphia’s population has grown, in total, since its population began ticking upward again in 2006 (we’ve only added 76,581 in total since).

Without immigrants, Philadelphia’s population would still be in decline. It took the city a long time to start capitalizing on the change in immigration law that went into effect in 1965. As recently as 1990, more than 90 percent of city residents identified as African-American or non-Hispanic white, and much of the rest of the population was Puerto Rican.

But Pew’s State of the City report shows that 13 percent of the current Philadelphia population was born outside the United States, which is close to the national average and just a percentage point behind the District of Columbia (and well over twice the rate of still declining cities like Detroit and Cleveland).

The largest share of this population comes from Asian nations, primarily China, India and Vietnam. Overall, 14 percent of the city is Hispanic, 7 percent is Asian, while 23 percent of the population speaks a foreign language at home. African-Americans represent 41 percent of the city's population, and non-Hispanic whites account for 36 percent (down from 41 percent in the 2010 Census).

In recent years, immigration to the United States has slowed as the economies of developing nations improved, political opposition to immigration increased, and harsher immigration restrictions were implemented. And as the increasingly shrill anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Republican Party reaches a fever pitch in the 2016 presidential campaign, there are fears that immigrant dependent cities like Philadelphia could face trying times ahead.

“If you look at the Census numbers every year, there is still a net domestic outflow [from Philly], but a net foreign inflow and they usually balance each other out more or less,” says Larry Eichel, director of Pew’s Philadelphia Research Initiative. “Sometimes the domestic outflow is bigger than the foreign inflow and then the other factor is the natural increase from birth (which explains continued population increase in those years). … Immigration has been a huge factor in the population growth of this city, and if it were to stop that would be a big deal.”

Measuring homicides is sometimes seen as the best indicator of a city’s crime problems because it is far harder for officials or criminals to obscure the number of murders than it would be to hide robberies (which can go unreported even by the victims), for example.

The most dispiriting statistic in Pew’s State of the City report is that the number of homicides in 2015 jumped to 280 from the historic lows of 2014 and 2013 (when the number dropped to 246). Last year’s murder count is still a marked improvement from the recent peak of 406 in 2006 and the far worse numbers of the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s.

Indeed, in a year when some cities saw fearsome increases in homicides, Philadelphia seems to have been largely spared. Baltimore, by contrast, saw 344 murders, despite the fact that it has roughly a third of Philadelphia’s population.

A better measure than the raw numbers is the rate of homicides per 100,000 residents, which was 17.9 in Philadelphia and a shattering 55.2 in Baltimore.

It is very difficult to say why murders surge in some cities and not in others. But it seems safe to speculate that the overall economic health of a city has some relation to violence, which is often a byproduct of shadow economies (like the drug trade) which are harder to regulate via norms and laws.

Violence and homicide have declined across the country since the gruesome peak of the 1980s and early 1990s. But in some very prosperous cities like New York, the numbers have continued to fall well into the 21st century while in urban areas like Detroit and Baltimore violence rates have leveled off. Pew’s State of the City report seems to show that Philadelphia is not yet taking part in this second, and more selective, the decline in urban violence.

Philadelphia’s poverty rate remains intolerably high, although it is down slightly from 2014. The city saw a 0.3 percent fall in poverty over the last year. The decrease is so tiny that it barely seems significant, especially when the way the United States measures poverty is widely considered inadequate. State of the City report doesn’t measure how many are close to the poverty line, but it isn’t difficult to see how the somewhat arbitrary measurement obscures just how badly many Philadelphians have it: 46 percent of households in Philadelphia earn less than $35,000 a year.

A big part of the city’s problem is that so many decently paying working-to-middle-class jobs have been relocated to the sprawling office parks and light manufacturing hubs in suburban locations with bad transit access. The Pew report shows that 31 percent of households have no vehicles available, which makes getting to a living wage job in Blue Bell or King of Prussia impossibly difficult.

Philadelphia’s growing population needs new places to live, whether more apartments for immigrants moving to the lower Northeast or new condos for empty nesters moving to Center City from the suburbs.

"2014 saw the highest number of residential building permits issued in Philadelphia since at least 1990, according to a Pew report on councilmanic prerogative from last year (which focused on the ways that some city council members are hindering that growth).

But today's State of the City report shows that the 2014 peak of 3,973 building permits was not surpassed last year. Instead, the number dropped to 3,666."

It’s worth noting that the more new residences are constructed, the cheaper the rents on existing housing will remain — one of Philly’s principal attractions – as those who can afford to buy or rent new are attracted to the fresher housing stock.

In a relatively mild residential market like Philadelphia, this should keep the housing prices lower in all but the hottest corners of the city, as long as developers keep building.

'State of the City'/Pew Research

'State of the City'/Pew Research