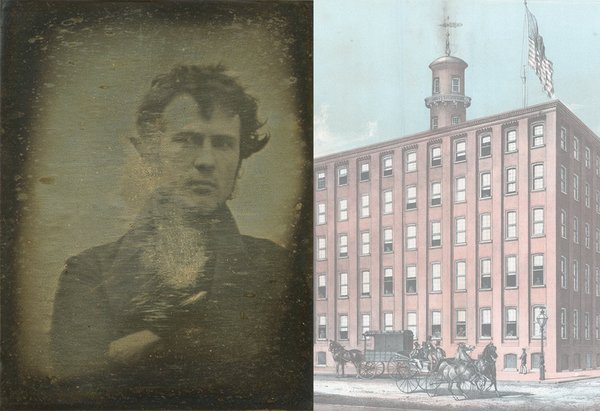

Robert Cornelius had to remain completely still for five minutes when he snapped the first so-called 'selfie' in a Philadelphia photography studio more than 175 years ago.

He couldn't even flash a smile for fear that a slight twitch would leave his face blurry.

"In the back of his studio, he exposed the lens, ran, sat still for five minutes and ran back," said Vincent Fraley, communications director at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. "You can see that his hand is partially blurred, but you have a pretty good sense of his face."

PHOTO GALLERY: Early photography developed in Philadelphia

Today, some 95 million photos are posted each day to Instagram, the social media giant that helped revolutionize modern photography. Undoubtedly, a significant portion of those photos are selfies – self-portraits snapped from an arm's length away.

But the concept of a selfie is not new, nor is the vanity that often prompts them. In actuality, it dates to the origins of photography in the United States.

Cornelius snapped his self-portrait in 1839, the same year another Philadelphia photography pioneer, Joseph Saxton, took the oldest extant photograph in America.

Both Cornelius and Saxton were among a small number of Philadelphia residents experimenting with daguerreotypes – the first form of photography, named after its French inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre.

"The reason why it took root in Philadelphia is that we had an established scientific community that was curious and we had an artistic community," Fraley said.

Cornelius, a chemist and metallurgist, had set up a photography studio in the back of his parent's lamp-making business near Eighth and Market streets.

"That's why people never smiled when they had their picture taken in this early motif. Even Miss America can't smile for 10 minutes." – Lee Arnold, HSP senior director of collections, on daguerrotype photography

His contemporary, Saxton, did not have that same advantage when he photographed the Philadelphia Armory and Central High School from the U.S. Mint at Chestnut and Juniper streets on Sept. 25, 1839.

The image, considered the oldest American photograph, is among the various collections housed by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.To capture the image, Saxton used a cigar box, glass lens and silver-coated, metallic plate. The image required 10 minutes of exposure time – an eternity compared to the billions of photographs taken in a flash on today's smartphones.

- RELATED STORIES

- NASA's curiosity rover snaps selfies on Mars

- Ecologists use over 300K animal selfies in Serengeti study

- The Philippines has the world's first selfie museum

"That's why people never smiled when they had their picture taken in this early motif," said Lee Arnold, HSP senior director of collections. "Even Miss America can't smile for 10 minutes."

To produce portraits, the early photographers used brackets to hold their subjects in place, ensuring the image would not become blurry.

Of course, Cornelius did not bracket himself in place when he posed for the first selfie.

Four years later, Cornelius captured Martin Hans Boyé in the first portrait taken for a book plate illustration. Boyd, a Central High chemistry instructor, did not use brackets even though his arms are positioned in the air.

"That's why it's so masterful," Fraley said. "But this is several years later, so the exposure time had decreased."

Yet, both Cornelius and Saxton mostly abandoned photography after a few years of experimenting with daguerreotypes.

Cornelius went on to run his family's lamp-making business. Saxton, a curator at the U.S. Mint, later invented the hydrometer, metallic cartridge for ammunition and improvements to the fountain pen.

"Even though he's indisputably the father of photography in North America, he's blurry at best in the history because he just didn't do it for that long," Fraley said. "Same thing with Cornelius."

Photography continued developing without them.

By 1846, there were more than 12 photography studios in Philadelphia, Fraley said. Exposure time had been reduced, limiting the length of time subjects needed to remain still.

But daguerreotypes remained an expensive endeavor mostly enjoyed by the wealthy. The portraits – often small in size and placed within a decorative case – served as mementos.

Given their thin, silver-coated plate, daguerreotypes were both reflective and subject to tarnish.

"Basically, if you see yourself in it, it's a daguerreotype because that's the way they did it," Arnold said. "It's just a layer of silver – that's how they made old mirrors."

The advent of the stereoscope in the mid-19th century brought photography into the hands of the common folk. Similar to a View-Master, early stereoscopes created a 3D image by viewing a pair of nearly identical photographs through a lens.

"This format of photography is the Instagram of its day," Fraley said. "It's the first photo craze. These things are within the reach of millions of Americans. There are dozens of studios here in Philadelphia."

During the Centennial Exhibition, held in Fairmount Park, several studios produced stereoscopic images of taxidermy, sculptures, dinosaur bones and other exhibits on display.

Stereoscopic images of Mayan ruins, Buddhist ceremonies and natural wonders were commonplace, Fraley said.

"Every day, 95 million images get added to Instagram," Fraley said. "But it's not our first photo craze. Stereoscopes were."