June 20, 2017

An advisory group tasked with reviewing Philadelphia's strategy to prevent childhood lead poisoning released its final report Tuesday, offering several recommendations to ensure the city continues to work with its residents and agencies to improve public health.

Formed by Mayor Jim Kenney last December, the advisory group was comprised of 22 representatives from healthcare organizations, advocacy groups, landlord and tenant groups, public agencies and external stakeholders at the state and local level.

The report's publication comes amid alarm over a Philadelphia Inquirer investigation examining how lead in the debris spread by construction crews has settled in the soil of the city's thriving River Wards neighborhoods, poisoning some young children who became exposed in their own backyards.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley addressed those concerns in a statement accompanying the report, whose recommendations seek to build on data showing a steady decline in childhood lead poisoning over the last decade.

“This report is a milestone for Philadelphia,” Farley said. "The levels we are seeing today – unlike those seen 50 years ago - do not cause obvious brain damage, but can cause subtle effects on behavior, attention span, and intelligence. Accordingly, our prevention and intervention techniques needed to evolve with this disease. I believe the Lead-Free Kids Plan we adopted in December and this report will get us there.”

Farley said the Department of Licenses & Inspections is tightening regulations to reduce and further contain the environmental effects of construction and demolition activity.

It’s important to remember that over the long term, replacement of older houses, through demolition and construction, will actually help reduce lead poisoning by removing the primary source of exposure for children – lead-based paint. And, furthermore, since lead tends to reside in the topsoil, construction and other earth disturbance activity can actually help reduce the risk of lead contamination from soil. While it’s true that demolition of older buildings can generate dust that may contain lead from the paint on the walls, it's important to note that this concern is lessened in Philadelphia, where demolition in occupied areas is usually conducted by hand, generating less dust.

The best things concerned parents can do is to wash their children’s hands regularly and to call Air Management Service complaint line (215-685-7580) if they see dust from a demolition or construction site. Please note that dust generated from construction is much less likely to contain dust particles than dust from demolition of a house that had lead paint, but you may still call the complaint line if dust is being generated beyond the property line for any construction or demolition activity.

About 95 percent of Philadelphia's housing stock — 580,000 owner-occupied and rental properties, according to U.S. Census data — have the potential of lead-based paint because they were built before the federal government banned its production in 1978. As many as 70 percent of these properties were built before 1950 and are at even greater risk due to higher amounts of lead in paint used at the time.

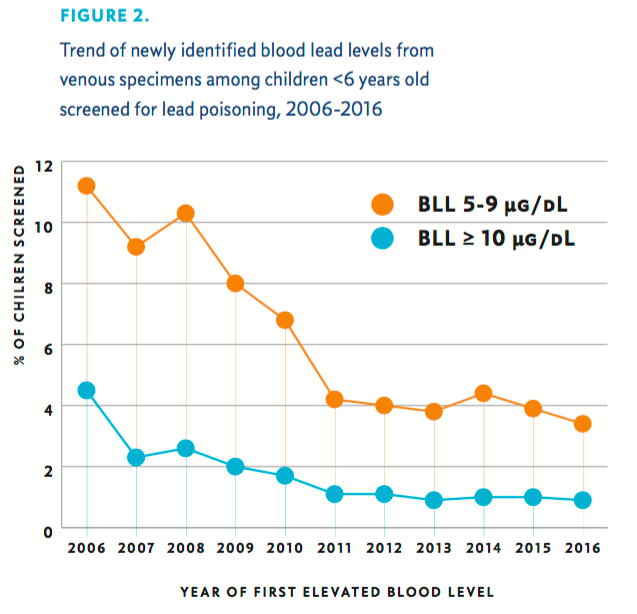

The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention currently sets its action threshold for childhood blood lead levels at 10 μg/dL, a reduction from μg/dL in 1991. A "reference" level of 5 μg/dL is used in individual cases to assess risk, monitor any increases in lead levels and to target primary prevention strategies in the aggregate.

In recent years, city officials have worked to increase lead testing among young children, which is often delayed beyond the recommended intervals of 12 and 24 months. In 2015, 41 percent of children born in 2012 had been tested twice by the age of three. But in total, 76 percent of children born in 2012 were tested by their second birthday and 88 percent were tested by their third birthday.

Lead screening trends in Philadelphia (2006-2010).

This progress has come despite a drop in federal funding and grants for lead prevention over the last five years, placing greater responsibility on the city to address the problem.

“While lead poisoning has dramatically declined in Philadelphia in recent years, we are committed to reducing its presence even further here in Philadelphia,” Mayor Kenney said in a statement.

The final report's recommendations call for a range of new initiatives and regulatory authority. Resident education and advertising campaigns will be backed by increased training for L&I inspectors, more enforcement and resources for landlords, engagement with pediatricians in underserved communities and targeted intervention at problem properties.

The advisory group's full report and recommendations can be accessed here.

Source/Philadelphia Department of Health

Source/Philadelphia Department of Health