April 13, 2022

Sarah Frank/for PhillyVoice

Sarah Frank/for PhillyVoice

In a U.S. real estate market with historic competition and low home supply, the Philly First Home grant program will resume in 2022 with down payment and closing cost assistance up to $10,000 for first-time buyers.

As the U.S. housing market revs up for another busy spring season in 2022, the prevailing feeling among many first-time home buyers is an anxious mixture of hope and fatigue.

Difficulty finding an affordable home to buy has been a common experience for people looking to own properties in Philadelphia, the surrounding suburbs and in communities all over the map in the United States. This has been especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, whose economic backdrop helped turbocharge residential real estate transactions.

U.S. home sales surged to a 15-year high in 2021, fueled by a combination of historically low mortgage rates, voracious demand and a low supply of homes for sale. The housing inventory problem, which preceded the pandemic, became even more critical as a result of delays in new home construction, higher material costs for builders and an avalanche of buyers vying for a shrinking number of existing homes on the market.

Now mortgage rates are quickly rising again, creating an unusual and uncertain market forecast that places the heaviest strains on first-time home buyers.

In the Philadelphia region, housing inventory has fallen nearly 41% below pre-pandemic levels to a decade low. The supply of homes for sale dropped 9.3% annually in December 2021, even as inventory showed signs of a mild recovery and the housing market appeared to cool a bit last fall.

Historically, in Philadelphia there is an average of about 7,400 homes for sale in the city at any given time. During the pandemic, that figure has hovered between 2,500-3,000 homes.

All of this adds up to a real estate market that has swung heavily to the advantage of home sellers, who in turn face the same issues as they attempt to move to new homes. When current home owners instead refinance at low rates, or otherwise stay put to avoid the headache of the market altogether, this reinforces the fundamental supply problem and contributes further to home-price inflation.

In Philadelphia, home prices increased by roughly 13% in 2020 and climbed another 6.3% by the end of last year, bringing the city's median sales price to about $255,000 in December. It fell to $242,000 in February, typically one of the slowest months on the real estate calendar.

For the metropolitan area, the median sales price rose to about $319,900 in February, nearly a 10% jump from the previous year. Compared to a decade ago, when the U.S. housing market began recovering from the 2008 crash, the metro area median sales price in Philadelphia is up more than 42% from $220,000 in 2012. During last year's competitive summer months, the median for the region reached about $325,000.

The Philadelphia area is far from alone. The national average median sales price leaped 16.9% annually to $346,900 in 2021, the highest increase on record, according to the National Association of Realtors, and has risen by about 32% over the last two years. By February, the inventory of existing U.S. homes for sale fell to a record low of 729,000– about a 48% decline from February 2020, according to nationwide listings site Zillow.

Even with encouraging signs for new home construction this year, analysts don't expect the inventory of U.S. homes for sale to rebound to pre-pandemic levels until late next year or 2024. The nation's share of first-time home buyers, which dropped from 45% in 2019 to 37% in 2021, may take longer to recover.

It can be an unforgiving market for different generations of buyers and sellers, each with different goals. Millennials are looking for reasonably-priced starter homes, while growing Gen X families want to size up and many Baby Boomers are holding out for the most comfortable retirement landings.

Anyone looking to buy right now may have a hard time finding and affording what they want, where they want it. First-time home buyers who are naive to the process face an understandably daunting predicament.

Without a mountain of cash, a sterling credit score and a comfortable income, the search for a place to call home can appear ruthless and demoralizing. Even buyers who possess these advantages may find themselves stretching beyond their means, waiving home inspections and other contingencies, or scratching important items from their real estate wish lists to get something done before mortgage rates rise higher.

Perseverance in today's market is not an exercise in futility, but the norm for many buyers is to endure an alternating test of patience and readiness to pounce, keeping fingers crossed that a little luck finds them.

Counting on such luck is not a promising option for people in low- and middle-income ranges. With fewer immediate resources, their outlook and path to home ownership does not seem quite as assured.

As Philadelphia looks for long-term strategies to make homeownership more attainable, could the approaching return of Philly First Home, the city's popular down-payment and closing-cost-assistance program, be a difference maker for the fortunes of priced-out buyers?

In a broader context, Philadelphia remains a relatively affordable place to buy a home. The blistering price inflation and bidding wars seen in the suburbs and in hot markets elsewhere in the country haven't yet touched every corner of the city's housing market. There remains a fairly large number of homes available below the median price in good, stable neighborhoods.

Still, the meaning of "affordability" depends greatly on the purchasing power of buyers, specifically when it comes to escalating down payment and closing costs.

As home prices keep climbing – and most market forecasts still project they will this year – these principal costs can quickly balloon from a stretch, to a barrier, to effectively being prohibitive of buying a home at all.

"Making a down payment is definitely the top struggle that a lot of my clients face," said Tia Whitaker, a Realtor with Domain Real Estate Group, a family-owned brokerage in Philadelphia. "I may have a number of (mortgage) pre-approvals for clients, but throughout the pandemic, I've seen that not only are home prices going up, but the fees of the down payment and closing costs increase, too."

Whitaker's division at Domain specializes in guiding first-time home buyers as they navigate the Philadelphia market. She helps these buyers determine where their finances best position them to invest in the city – not just in a home, but in a community as well.

Most of Whitaker's clients are low- and middle-income Black families with household incomes ranging from $45,000 up to $90,000. For these buyers, clearing the hurdle of steep down payments and closing costs often necessitates getting grant money to cover a large portion of the up-front expenses.

"It's an initiative of my business to seek out home buying grants," Whitaker said. "It takes about 10% down to purchase a home in Philly. If you're going after a $250,000 home, your closing cost is going to be around $25,000 with down payment and closing costs combined. Most families just don't have that."

A variety of down-payment assistance programs exist to help out first-time home buyers. The funding may come from sources such as banks, government entities and non-profit organizations. Many of these programs are available not just to low-income buyers, but also people with moderate incomes who do the extra research and apply.

Every grant program for first-time home buyers carries its own set of eligibility criteria, some more difficult to meet than others. They generally look at a buyer's income and credit score, offering them varying percentages of a home's sale price and different terms of forgiveness for the grant amount. That means the buyer must maintain ownership of the property that they purchase for a set period of time before the loan is wiped away.

In June 2019, Whitaker was among the first real estate agents in the city to participate in the Philly First Home Program, an initiative through the city's Division of Housing and Community Development. The program was part of Philadelphia's Housing Action Plan and expanded on previous down-payment assistance options, which had included small grants ranging from $500 to $1,000.

Whitaker had been teaching weekend home-buyer workshops at HUD-approved agencies in Philadelphia and received early notice of Philly First Home. The new program had generous terms offering grants of up to $10,000 – or 6% of the home's purchase price, whichever was less – to help buyers cover the down payment and closing costs on homes in the city of Philadelphia.

Prospective buyers seeking these grants could live outside Philadelphia as long they purchased in the city, and they had to be first-time home buyers or buyers who had not owned a home for at least three years.

The program had no minimum credit score requirement and the income threshold was set at 120% of the Area Median Income based on the size of the buyer's household. The calculation of AMI includes the higher earnings of people who live in the Philadelphia suburbs, meaning the upper income limit for the program opened it to a large population of city residents.

In a two-person household in 2019, for example, 120% of AMI put the maximum income for Philly First Home eligibility at $86,520. For one person, 120% of AMI was $75,720 and for a family of four, it was $108,120.

Three years ago, the median household income in Philadelphia was $45,927, according to the American Communities Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau.

When Whitaker heard about the program, she was thrilled to be able to help her clients access grants that didn't have the same credit restrictions, loan terms and income limits as other popular programs. Credit, in particular, can be a major snag for grant seekers in other programs.

"Philly First Home wasn't as strenuous with the guidelines," Whitaker said. "Some buyers may have a clean credit report, but their scores aren't as high because of issues that they had five to 10 years ago, so they don't meet criteria for other grants. If you think about the demographics here, many people can purchase a home ideally with a credit score of 620, but if they can't get a grant because the cutoff is higher, it leaves them hanging in the balance."

The only major requirement of Philly First Home's first run was that all participants in the program had to complete a four-hour workshop with a HUD-approved agency in Philadelphia and then attend at least one individual homeownership counseling session. Counseling requirements are not unusual for many grant programs.

"That is extremely important," Whitaker said. "It ensures that the client is educated about what they're going to do, and the road to foreclosure is cut down because they know what they can afford."

After receiving the counseling certification for Philly First Home, a buyer would go search the city for a home. Once an agreement of sale was completed, the buyer would return to the housing counselor, who would submit a final application making the grant money available to the title company.

"It was a very smooth process," said Whitaker, who closed more than 40 deals with clients using Philly First Home grants.

The broad eligibility for Philly First Home grants meant that a significant pool of potential buyers, families who might otherwise have had little shot at homeownership, suddenly had a chance to get assistance with their single biggest roadblock.

Philly First Home generated instant and insatiable demand in the late spring of 2019, burning through its first $3 million budget in a matter of months.

"We didn't expect that it would catch fire so much," said David Thomas, president and CEO of the Philadelphia Housing Development Corp., the quasi-municipal non-profit that oversaw a portion of Philly First Home. "It caught us all off guard. The demand was much greater than the supply."

The city's initial $3 million commitment and another $2.5 million planned for 2020 was soon supplemented with $8.5 million from Wells Fargo, which had settled with Philadelphia over its predatory mortgage lending practices leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. The settlement was part of a wave of litigation that led to the creation of similar housing assistance programs in other states and cities, including Baltimore.

With a flood of Philly First Home applications and pre-approved buyers out looking for properties, the city created additional dollars for the program by allocating money from the Housing Trust Fund, which has a range of revenue sources intended to funnel resources toward affordable housing.

"We had a huge pool of folks who completed the counseling certification, and while they were off looking for a home, we would not know how many had executed an agreement of sale at any given point," said Melissa Long, director of Philadelphia's Division of Housing and Community Development. "When we knew we were getting low on funds, we had to give a three-month period to allow people to complete that process."

Over an 18-month period ending in October 2020, Philly First Home became a $24.26 million program that helped 2,701 families purchase homes in the city. The average grant amount was $8,983.33 and the average home sale price among buyers who received grants was $174,435.33.

All of the grants provided by Philly First Home became a lien on the property's first mortgage for 15 years. The sum of the grant will be owed back to the city upon the property's sale, if it was sold in less than 15 years, or if the owner refinances within that 15-year-period. Otherwise, the grant is forgiven.

The city ultimately benefits by growing its tax base and generating new revenue on properties that will presumably increase in value during those 15-years and beyond. Purchases made using program funds generated more than $15 million in real estate transfer tax revenue and more than $537,000 in deed recording fees. Some of this revenue was reinvested in Philly First Home.

A home for sale on the 3700 block of Manayunk Ave in the Wissahickon neighborhood of Roxborough.

"A lot of times, people are cash-strapped once they get into their property, and there's still some investment necessary for them to move into a house or make some fixes," Thomas said. "We try to make sure that people are not going into a situation over their heads or underwater. This gives them some cushion to make a smooth transition into homeownership."

City officials deemed Philly First Home a great success, but soon recognized that the fiscal crunch of the pandemic would leave its future in question, just as the housing market was getting tighter for buyers.

"There are so many people who may have decent credit, and maybe they can get a mortgage and they can pay it, but they just need a little help," said Jamila Davis, spokesperson for PHDC.

"This was a necessary program for Philly," Whitaker added. "And that's why it ran out so quickly. It didn't price out the people who really needed it."

In the frantic residential real estate market now facing home buyers in 2022, Philadelphia is on the verge of bringing back Philly First Home for a four-year period that will budget $14.5 million annually for down-payment assistance grants.

The funding was approved in 2021 by City Council and Mayor Jim Kenney as part of Philadelphia's $400 million Neighborhood Preservation Initiative, a sweeping plan to invest in affordable housing, home repairs, small business revitalization, rental assistance and eviction prevention.

Philadelphia will finance the Neighborhood Preservation Initiative with bonds issued through the treasury office and the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority. The first $100 million in bonds were issued in October, drawing interest primarily from large institutional investors.

"I already have all the banks calling me because they've heard whispers that it's coming back, so they're trying to line up and get themselves prepared to provide additional resources to their borrowers," Thomas said.

This time around, there will be some adjustments to the program, including a revision of the Area Median Income eligibility down to 100% from from 120%.

Only a small portion of people who obtained Philly First Home grants in the first round of the program were above 100% AMI. It's possible that those earning above 100% AMI were candidates for other grant programs that offered friendlier terms for their individual circumstances, such as a shorter forgiveness period or more than $10,000 toward closing.

"We don't believe this change is going to be a major hit on our program," Thomas said.

The 2022 AMI calculation for a family of four in the Philadelphia area is $94,500, a figure determined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The chart below shows the AMI eligibility figures, by household size, that will be used when Philly First Home resumes. (Note: These numbers will change in future years).

| Family Size | AMI at 100% |

| 1 | $66,150 |

| 2 | $75,600 |

| 3 | $85,050 |

| 4 | $94,500 |

| 5 | $102,000 |

| 6 | $109,650 |

| 7 | $117,200 |

| 8 | $124,750 |

Additional details about the the return of Philly First Home will be revealed when the program is formally announced, which is expected in May.

The biggest questions facing Philly First Home now revolve around changes in the housing market since the program ended in October 2020.

"The market was just starting to heat up when our program was ending, so some of the horror stories that you hear about homeowners paying $100,000 above asking price – that didn't really happen during the duration of the program," Davis said.

More real estate inflation and competition among buyers, many of whom tried and failed to purchase homes during the last two years, could mean the program now will operate in a more cost-pressured environment.

Whitaker believes Philly First Home will thrive, much the way it did in 2019-2020.

"It opens up more doors and more inventory to buyers," Whitaker said. "A lot of first-time home buyers don't want to get a home and have to re-do it. They want a move-in ready home, mainly because they don't have the money to make those fixes."

There are other changes and barriers in the housing market that these grants could alleviate. At a time when sellers have the upper hand in negotiations, buyers are less likely to be able to work out a seller assist to cover closing costs, which usually amount to 2-5% of the sale price.

"I think that it will give buyers a stronger competitive edge," Whitaker said. "It was a lot easier for me to get my (Philly First Home) clients' offers accepted because we weren't going in asking for a seller assist. Our needs weren't the same. If a home needed new cabinetry in the kitchen, for example, my clients would feel more comfortable going after a property and addressing that later because they didn't have to put out $15,000 or more in their own closing costs."

City officials believe the demand seen during the initial rounds of Philly First Home will return.

There is tempered optimism that increases to mortgage rates could moderate home prices and add to stock of homes for sale as some sellers try to capitalize while home values remain high. If rates increase too much, however, the shift could also price many buyers out of mortgages and could push others on the bubble to jump into the fray before rates rise more and become prohibitive long-term commitments, even if they have the up-front cash.

The Federal Reserve's move to raise interest rates, spurred by inflation and the conflict in Ukraine, has pushed the average 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage up to 4.72% in April. It had remained under 4% throughout 2021 and once fell as low as 2.68% in late 2020.

This type of change makes a substantial difference in affordability, particularly in a market that already has experienced historic home-price inflation.

The average monthly mortgage payment in the U.S. for a 30-year, fixed-rate loan rose to $1,230 per month at the beginning of March. It's the highest level on record, according to data from real estate site Zillow, and a 36% increase from the average of $905 per month a year ago.

The uncertainty around mortgage rates has led to wildly divergent real estate forecasts heading into the spring season.

Some market analysts, wary of rates climbing higher than expected this year, have revised their projections accordingly. CoreLogic, a real estate research company, believes year-over-year U.S. home price growth from January 2022 to January 2023 will be just 3.8%, a below-average annual increase. Zillow, on the other hand, still expects year-over-year home price growth to hit 17.8% from February 2022 to February 2023, with prices accelerating through May of this year based on sustained high demand and low inventory.

In historical context, the average annual rate of U.S. home price growth since 1986 has been about 4.6%.

In the Philadelphia metro area, annual comparisons between months show that home price growth has remained well above this benchmark. Bright MLS housing data from February reported median price increases of at least 7% year-over-year every month for the previous 20 months, including some months that came in much higher. Home prices in the region soared by 14.7% in Dec. 2021 compared to Dec. 2020.

First-time buyers face a bleak outlook, one in which they'll be stung by a trifecta of high home prices, higher monthly mortgage payments and higher-priced rentals in the event that they are unable to purchase homes.

But Whitaker doesn't feel her clients should be discouraged from buying this year if they have the fundamentals in place to afford a home. Delaying action does not necessarily mean market conditions will be favorable in the foreseeable future.

An open house sign sits on a street corner in Fishtown.

Whitaker said rising prices in the Philadelphia area have been expected based on trends over the last five to 10 years in the surrounding markets of New Jersey, New York and Washington, D.C., which usually signal changes that will catch up around here.

"We are due for home price inflation," Whitaker said. "I think that's just one of the natural things that's going on."

Davis wonders whether more Philly First Home grants might hit the full $10,000 threshold if 6% of the purchase price surpasses that amount more frequently this time around. The price point at which that happens is a home that sells for approximately $167,000.

The rate of sales in Philadelphia is not as rapid as in the suburbs, where inventory is much tighter from month to month and competition is greater. In Philadelphia County, homes remained on the market in February for a median of 47 days, according to The Long & Foster Market Minute. That figure stood at 30 days in Montgomery County, 27 days in Chester County, 24 days in Bucks County and 28 days in Delaware County. Nationally, the typical home spent 47 days on the market in February.

A buyer looking in the Philadelphia area can expect sales velocity to pick up this spring, leaving even less time to assemble an offer on a property – let alone see it.

The Philadelphia market, although faced with low supply and fewer active listings than a year ago, fortunately is in better shape than many other cities and towns in the United States. There is optimism that more sellers will be comfortable listing their homes in light of greater stability around the pandemic. They may be looking to capitalize now while higher home prices persist into the busiest real estate months of the year.

Data from Redfin shows about 25% of single-family homes in Philadelphia sold above list price in February and 19.6% had price drops, with only minor year-over-year fluctuations.

These two metrics tend to be less favorable to buyers during the spring and summer months.

Last year, nearly 35% of single-family homes in Philadelphia sold above list price in May, rising to about 45% by June. The percentage of price drops was actually higher during much of 2021 than it is now, hovering around 30% from June through November, but this can be a misleading statistic depending on overall market conditions.

Sellers often lower home prices to create more foot traffic from buyers and drive up bidding beyond the home's previous list price. When home supply is low and demand is high, price drops serve as marketing decoys that can increase the number of homes sold above list price.

First-time buyers in Philadelphia should anticipate that competition for individual properties will remain a factor given the sudden urgency around rising mortgage rates, with some reason to have hope that listings will increase and prices may soften later in the year.

Buyers who struggle to find the right combination of home attributes and price may also decide that the most prudent action is to simply hold off on making purchases, instead of pouncing out of desperation. In one Zillow survey, 75% of people who bought homes during the pandemic admitted that they had regrets, most often that their homes are too small and that the properties they bought need more work than expected.

Beyond this kind of broad conjecture, the experience that Philly First Home grant recipients will have in this year's market remains to be seen.

"The pandemic didn't stop demand for the program in 2020," Thomas added. "You would think that might slow things down, but folks were still buying houses even if they had to look at them virtually. The real question is, 'What has changed in the market?' Is it just as hot as it was when we shut Philly First Home down? There's a lot of bidding going on now and employment challenges out there, things that didn't exist as much when the program launched. I think all of that is still unknown."

Pennsylvania's unemployment rate fell to 5.1% in February, the lowest it has been since the start of the pandemic. In Philadelphia, the unemployment rate began 2022 at 7.7%, down from a peak of 19.5% in July 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, but it remains above the national unemployment rate of 3.8% in February 2022. The city's job recovery from the pandemic has lagged behind the national economy, particularly in low-wage sectors, and Philadelphia was disproportionately hit by the downturn compared to other major U.S. cities.

If the past is a strong predictor of what may happen in the coming months and years of Philly First Home, the data from 2019-2020 suggests that among the new first-time home buyers who currently rent in Philadelphia, the majority will look to purchase homes either in neighborhoods where they currently live or within a few miles.

The geographic distribution of homes bought through Philly First Home offers insight into how well the program works.

City officials provided PhillyVoice with key statistics and maps that break down what buyers chose to do with the grants they received. This includes demographic information, home price information and a look at the neighborhoods grant recipients most frequently targeted.

The first table shows how household incomes of the first 2,701 grant recipients in the Philly First Home program compared to the Area Median Income, which was based on income figures from 2019.

| Area Median Income | Percentage of Philly First Home Grants |

| 50% AMI or Below | 22.29% |

| 51%-80% | 43.1% |

| 80%-120% | 34.62% |

The second table shows the distribution of sales prices of properties purchased by Philly First Home buyers.

| Sales Price | Percentage of Homes Purchased with Grants |

| < $100,000 | 5.55% |

| $100,000-$149,000 | 28.66% |

| $150,000-$199,000 | 39.17% |

| $200,000-$249,999 | 17.92% |

| > $250,000 | 8.7% |

The third and fourth tables show the distribution of Philly First Home buyers by race and ethnicity. The program did not keep statistics on buyers' ages.

| Race | Percentage of Philly First Home Buyers |

| Black | 57.41% |

| White | 19.59% |

| Asian | 3.07% |

| More than One Race/Other | 19.93% |

| Ethnicity | Percentage of Philly First Home Buyers |

| Hispanic or Latino | 26.3% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 73.7% |

As the tables above illustrate, Black home buyers comprised the largest racial demographic in the program, though there also was substantial participation among Hispanics and whites.

"We didn't try to approach any one demographic. It was just a byproduct of this program that a lot of minority buyers became first-time homeowners," said Davis, of the city's planning and development department. "We're focused on trying to get people to be homeowners in Philadelphia, and it just happened that the majority of those folks were minorities. It helps all people in a middle income range buy their first home, no matter their color. And if it happens to be Black and Brown people, this gives them a chance to create generational wealth."

It is important to note that the outcomes of Philly First Home reflect the independent decisions of buyers in the private, residential real estate market. That begins with the choice to participate in the program's required counseling certification and to accept that grants come with a 15-year commitment in order to get the lien forgiven. This makes the choice of a neighborhood to buy in much more consequential.

"The market was able to drive it. I think that's what made the program so fantastic," Thomas, of the Philadelphia Housing Development Corp., said. "We didn't have to push this program at all. Once the gate opened, the flood came. Realtors, mortgage lenders, everyone was very much interested in figuring out how they could help people become homeowners. The barriers and challenges to homeownership were definitely mitigated."

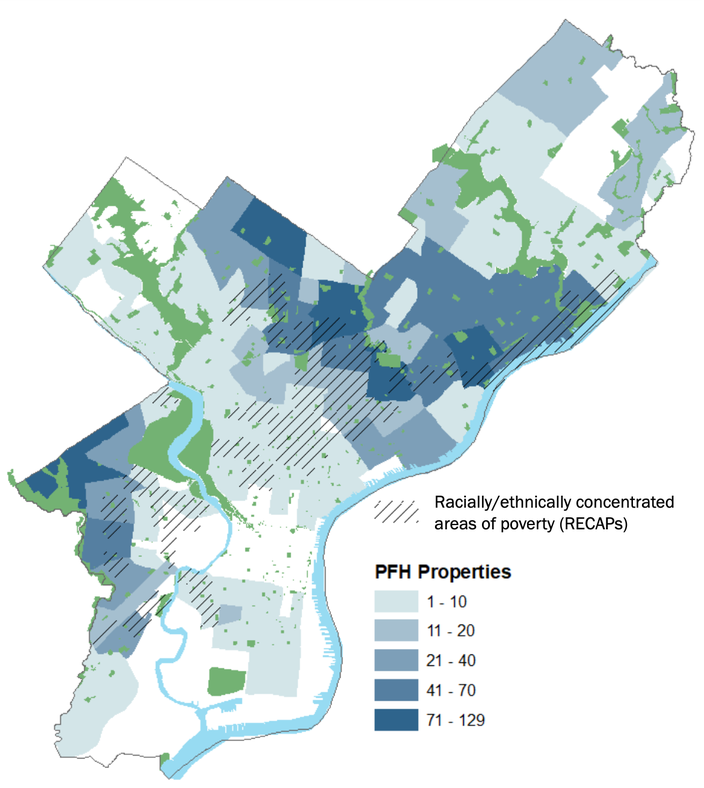

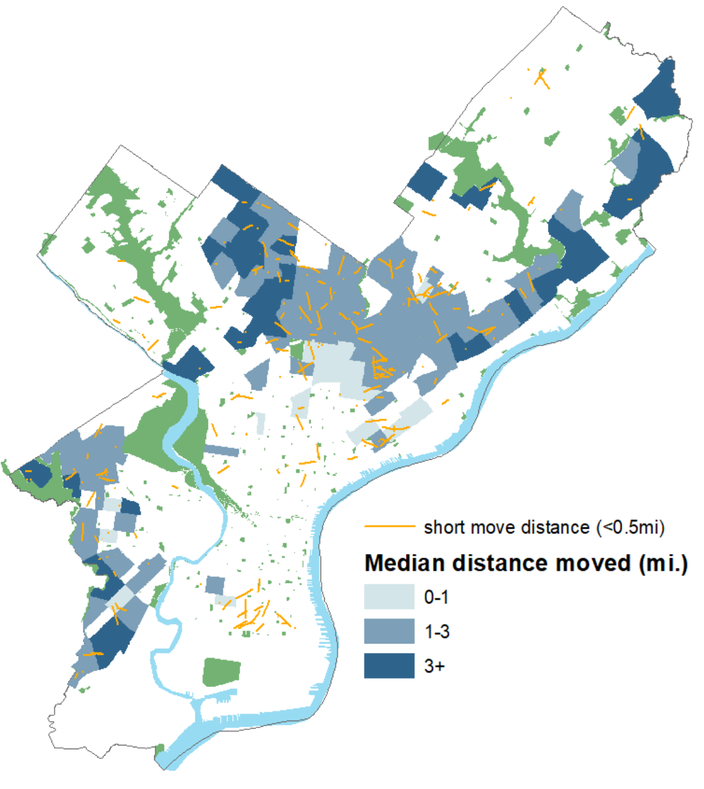

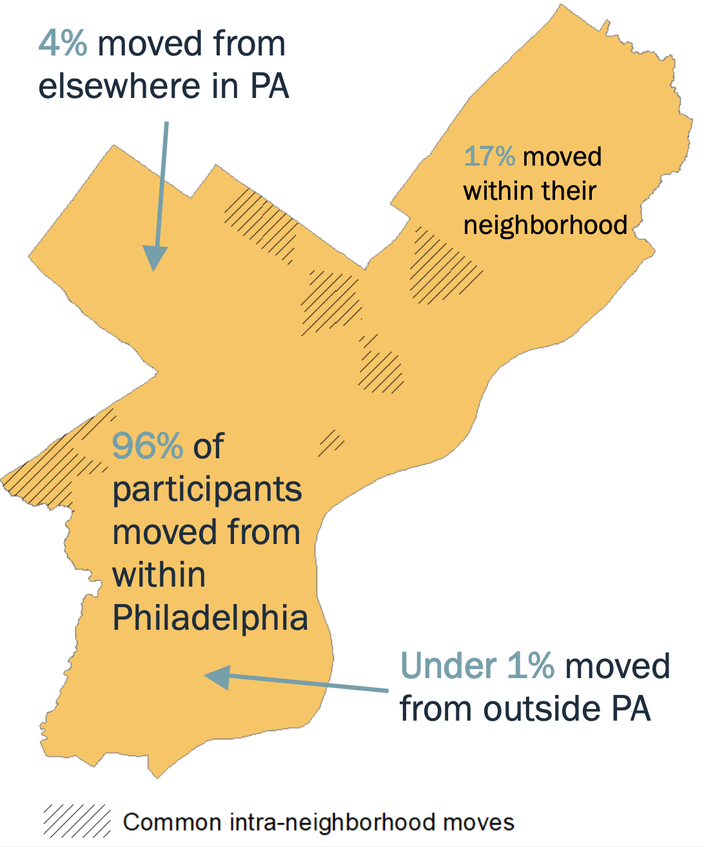

(Note: The following maps were created by the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation)

The three maps below show snapshots of home buying trends among 2,000 grant recipients between January 2019 and July 2020, about three months before the program ended. This also includes several months of buyers who received much smaller grants during the period before Philly First Home expanded to offer up to $10,000 in assistance.

In the first map, areas in the darkest shade of blue were the most popular for grant recipients to buy homes. The series of parallel lines indicate racially/ethnically concentrated areas of poverty – or RECAPs – a HUD-defined category for census tracts where more than 50% of residents are non-white and incomes fall disproportionately below the poverty line. These accounted for about 15% of homes of the homes purchased in this sample of 2,000.

The second map illustrates how far grant recipients moved when buying a home. More than 60% of participating households relocated less than three miles from their previous addresses, including 25% who moved within easy walking distance of the last place they lived.

The third map shows that most people who participated in Philly First Home already lived in the city. Only about 5% came from outside the city or state, and 17% bought homes in the same neighborhoods where they had been living. On this map, the parallel lines show places where intra-neighborhood moves were most common: Olney, Oxford Circle, Juniata Park, West Oak Lane, Overbrook and East Kensington.

In addition to the neighborhoods noted above, the most popular neighborhoods for Philly First Home buyers were in Northeast Philly and West Philly, with pockets of Northwest Philly and Southwest Philly comprising a larger-than-average share of homes purchased by grant recipients.

Considering that more than 65% of grant recipients had household incomes between 51%-120% of AMI, the Philly First Home program ended up serving a fairly large proportion of middle-income residents, not just low-income home buyers.

"If you look at where there are the most Philly First Home purchases, those are reasonably integrated, mixed-income neighborhoods," said Ira Goldstein, president of policy solutions at Reinvestment Fund, a mission-driven financial institution that invests in underserved communities and has offices in Philadelphia. "The neighborhoods that are in the lower part of the Northeast are mixed racially. If you go into Logan and Olney, those will be racially mixed. West Oak Lane, East Mount Airy, Cedarbrook. These are the solid middle neighborhoods in Philadelphia."

Goldstein is among a group of urban policy researchers who believe that strengthening "middle neighborhoods" is an essential part of fostering sustainable growth. These neighborhoods offer residents a path to affordable homeownership while minimizing the most egregious forms of gentrification and displacement.

Middle neighborhoods usually exist somewhere on the edge of growth and decline. They aren't the strongest neighborhoods, but they often have a good housing stock and would not be considered distressed. The quality of life there is high enough and stable enough that new homeowners are willing to bet on the future of their employment prospects, education and crime rates.

"These neighborhoods are economically attainable," said Goldstein, who considers Philly First Home an example of positive investment in these places.

The guiding idea behind supporting middle neighborhoods is that cities can take action to prevent them from slipping into dire states that would be much harder to reverse. The point is not to invest in middle neighborhoods instead of putting resources into RECAPs, but rather to recognize that the support middle neighborhoods require is less costly, by comparison, and advances a real path to mobility for residents.

"Middle neighborhoods stand as the living and breathing examples of the fact that people of different races and national origins can live together in a decent way," Goldstein said. "It's a pretty important part of the strategy of closing the wealth gap between white people and Black, Hispanic and Asian people."

A home for sale in Northeast Philadelphia, a popular place among Philly First Home grant recipients who favored the city's 'middle neighborhoods.'

"If people are buying homes in neighborhoods they've long lived in, then this is a program that could perpetuate the segregation that was baked into housing markets a long time ago," said Gregory Squires, a professor of sociology and public policy at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. "It's not by design. I'm not suggesting that anybody in the city of Philadelphia is out to perpetuate segregation. But in effect, that can happen when a program purports to be colorblind."

Squires suggested that the dilemma facing policymakers boils down to a question of scope, and how to best deal with the practicalities of the private housing market.

"Should the goal be to help people access neighborhoods that have been traditionally inaccessible to them, or should the approach be to just help as many people as possible be able to afford a home? Is the goal reinvestment or integration?" Squires posed. "Housing affordability policies that take the existing housing market as a given – and try to make marginal adjustments, given the realities of the private market – put great limitations on what might happen right from the start."

The choices of so many Philly First Home buyers to purchase properties near where they were renting also could be chalked up to simple preference, at least in part.

"Some people likely wanted to stay in their neighborhoods because they have support structures already there – parents, grandparents, babysitters," Thomas said. "It's all predicated on the individual. There's a lot of naturally occurring affordable housing in the districts where many people bought homes that fit their price ranges."

Goldstein agrees that these are reasonable factors for many people who are looking to buy a home.

"There is an aspect of having to consider, 'What do people choose?' If someone moves from one part of West Oak Lane to another part of West Oak Lane, it may be because people become comfortable in their neighborhoods. They live there for a while as a renter, perhaps, and then they decide that if they can own there, they'd like to be there. I don't think that's necessarily bad. Philly First Home was not designed as an integration program, and I don't think it necessarily functioned as an integration program. But people were able to find homes."

There are important factors to consider when choosing where to buy a home in Philadelphia.

Many Philadelphia neighborhoods suffer from structural disadvantages that reflect the legacy of redlining and residential displacement due to redevelopment. In one of the nation's poorest big cities, large pockets are held back by failing schools, disproportionately high crime rates, limited economic opportunities and the uninspiring surroundings of blight.

An investment in home ownership in these places, where properties may cost less, is a big gamble for lower-income buyers and risk-averse banks – especially when compared to the same lenders doing lucrative business with speculative investors.

Among the sample of 2,000 Philly First Home buyers reflected in the maps above, roughly 40% moved to areas with lower property values than the neighborhoods they left. About 30% moved to areas of similar value and another 30% moved to higher-value areas.

"One way to try to improve the program during the counseling phase is to help future home owners choose a neighborhood that is better in certain dimensions, whether it's income, commuting, school quality and so on," said Fernando Ferreira, a professor of business economics, real estate and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. "There's a lot of research showing that neighborhoods matter, especially for kids. There's data that counselors can use to guide families to neighborhoods that will be better for kids."

One of the largest HUD-approved counseling agencies to participate in Philly First Home is the Affordable Housing Centers of Philadelphia, which submitted approximately 800 of the 2,701 grant applications to the program.

The Fair Housing Act prevents counselors from giving opinions or recommendations about what constitutes a preferred neighborhood, explained AHCP executive director Ken Bigos. His counselors work closely with buyers to look at their incomes and debt-to-income ratios in order to gauge what size mortgages they can comfortably afford.

"We're the personal trainers to their housing and financial goals," Bigos said. "We offer broccoli, and the grants are the chocolate cake. Our real purpose is to ensure long-term success for people who are making life-changing decisions."

Not surprisingly, the availability of grants correlated directly with participation in the agency's counseling workshops.

"We had more participants in our education workshops in the first two months of Philly First Home than we had in the previous 12 months combined," Bigos said.

Housing counselors have an important role, but many of them are spread thin with heavy case loads. In addition to working with home buyers, their services include helping households facing foreclosure and guiding renters in Philadelphia's eviction diversion program. In a housing market full of obstacles to overcome and cracks for people to fall through, many counseling agencies offer free services with limited resources. They do their best to steer clients toward prudent financial decisions and investments.

"At the one-on-one sessions, the counselor will tell clients, 'This is the maximum monthly (mortgage) payment you can have to be eligible for the program,'" Bigos said.

In practice, much of the responsibility for guiding buyers into new homes falls on real estate agents, who have a clear financial stake in the sales they facilitate. Buyers have to strike an optimal balance between finding the right property and picking the right neighborhood when there's such high competition for homes.

"I'm definitely one to challenge my clients to think differently," said Tia Whitaker, an agent with Domain Real Estate Group. "I urge them to purchase strategically. The closer you are to Center City, the better to buy. That's where we're seeing our trend of how the real estate market is going. The closer you are to downtown, the more quickly you can you get there, the better it is to buy."

Most of Whitaker's first-time home buyer clients are Black, she said. When they talk about where they would like to start searching for a home, they often are interested in looking at neighborhoods outside of where they currently live, sometimes mentioning crime and safety as concerns. This contrasts a bit with the Philly First Home data on moves that were largely made within or near the neighborhoods where grant recipients had been renting.

"They are looking for areas where they feel they can be a little bit more stable and comfortable," Whitaker said of her clients.

The most popular areas among Whitaker's home buyers include Mount Airy, Roxborough, Wynnefield, Overbrook, parts of South Philadelphia, and to a lesser extent, Northeast Philadelphia.

Certain neighborhoods that were long associated with cheaper homes also have seen property values increase, for various reasons. Whitaker grew up in North Philly and pointed to the 19121 ZIP code, which covers Brewerytown and Strawberry Mansion. These neighborhoods now exist unevenly between gentrification and distress, making them a complicated proposition for first-time buyers.

"You could buy a house there 20 years ago for $5,000 – at most," Whitaker said. "To purchase a property today in 19121, it's ranging anywhere between about $250,000 and $450,000. That's depending on new construction, rehab, etc. We see these changes in a lot of our neighborhoods. With the low inventory, buyers may get pre-approved for a mortgage, but they also have to look outside their neighborhood because the prices have gone up for what they want in a home and community."

There is a push among fair housing advocates to create more opportunities for people of color to integrate in neighborhoods where the private market prices them out of homes, whether they are rentals or places to own. At the most radical end of the reform spectrum, fair housing proponents contend that an affordable home should be a guaranteed basic right rather than a commodity subject to market fluctuations.

Squires said the issue touches on a longstanding and heated debate even among progressives, who consider racial mobility in the housing market an important goal.

"Some fair housing advocates are adamant that things, like Section 8 and housing choice vouchers, continue to be concentrated in all Black neighborhoods, perpetuating racial segregation, when jurisdictions should be making a greater effort to provide those vouchers to families that are moving into whiter neighborhoods," Squires said. "Others believe that what we need to do is just provide more vouchers and housing opportunities for people regardless of where they want to live – and that people have the right to stay put in neighborhoods if they want, with the expectation that schools and streets will be safe, and jobs and amenities will be there. In other words, that the mobility thrust of many fair housing advocates is well-intentioned, but misplaced."

The middle ground some reformists suggest is to recognize that people understandably look for homes in neighborhoods that they know and understand, where they have histories. Chipping away at the cycle of segregation should instead come in the form of education that empowers choice.

"The argument is that part of the policy goal should be to provide counseling to help show people neighborhoods that they may not be as familiar with, so that they choose among a broader range of housing options," Squires said. "By having that kind of knowledge, advice and support, more people will make pro-integration moves."

In its current format, the primary objective of home ownership counseling is to help buyers make necessary cost assessments for obtaining mortgages and managing expenses.

The most immediate benefit to low- and middle-income buyers may be that counseling can connect them with the best grant opportunities available to save money at any given time.

In addition to Philly First Home, many of Whitaker's clients use other grant programs for first-time home buyers, such as First Front Door and the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency's K-FIT and Keystone Advantage programs. Bank of America, Wells Fargo and other large banks periodically run grant programs in select U.S. markets, too.

Neighborhood LIFT, a recurring program from Wells Fargo, has offered down payment assistance up to $15,000 to hundreds of Philadelphia home buyers in the last decade. The program's past rounds have focused on qualified low- to moderate-income buyers, about half of them Black or Hispanic, who obtained grant approval from Wells Fargo's partnering lenders.

The Neighborhood LIFT program is not expected to return to Philadelphia in 2022, a Wells Fargo spokesperson said, but likely will in future years. First-time home buyers in Philadelphia can still get counseling funded by Wells Fargo's philanthropic arm.

Informed home buyers always will have a leg up simply by seeking counseling, but the larger challenges of the housing market go beyond what any down-payment assistance program can scale to address.

The return of Philly First home will create thousands of new homeowners in Philadelphia in the coming years. The city believes this represents substantive progress not just in finite terms, but in the model of choice it advances.

"People want to live where they want to live," said Davis, with the Philadelphia Department of Planning and Development. "What makes Philly First Home great is that it doesn't push people to live on a certain block or development. If you get approved for a mortgage, you can live wherever you want. Often times in city government, we have to be responsible in following restrictions with federal funding. Philly First Home gives people the freedom to choose."

Ferreira, the Penn professor, acknowledged the value Philly First Home will have for the families it helps in the coming years, but is skeptical about its overall impact when comparing the program's cost to the number of people it can benefit and the glaring supply shortage that needs to be prioritized.

"The best plan for neighborhoods would be to grow, to expand, to bring more people in," Ferreira said. "There is a direct and straightforward way of doing that through policy, and that is allowing and incentivizing a lot more construction in all of these neighborhoods. As you have a bigger supply of homes, the prices of those homes are going to be cheaper and it's going to be easier for everyone to buy and rent. This can be done without increasing cost of living and displacing too many residents. In fact, it should help local residents stay."

Evaluating the success of the city's first-time home-buyer program depends on considerations beyond the program's obvious purpose of helping people achieve home ownership. On balance, it is a relatively small intervention in a city that faces present and future affordability challenges for renters and homeowners, who are affected disproportionately based on race and class.

Out of 601,000 total households in Philly, about 53% own their properties and 47% rent.

The proportion of renters in Philadelphia has steadily risen since the turn of the century, a trend that's consistent with other large U.S. cities. Between 2000-2017, Philadelphia lost more than 100,000 homeowners – an 11% decline – and gained more than 157,000 renters – a 30% increase – according to U.S. Census data.

Factors influencing this shift may include construction of more rental units compared to single- and multi-family homes, the changing age demographics of cities and overall population and socioeconomic trends. Philadelphia's population declined during the second half of the 20th century, dropping from a peak of about 2 million in 1950, and has recovered modestly in the last two decades to just more than 1.6 million today.

Some cities similar in population to Philadelphia – such as Dallas, San Diego and San Antonio – experienced growth in owner-occupied and renter-occupied homes between 2000-2017. Others including Baltimore, Memphis and Akron followed a path similar to Philadelphia's, experiencing stark declines in owner-occupied homes as renter-occupied properties increased.

At Reinvestment Fund, some of Goldstein's projects have involved interviewing aspirational first-time home buyers, including people who have purchased in Philadelphia and received grants from Philly First Home.

"Universally, they said that this $10,000 – or up to $10,000 – was the difference between being a buyer and not," Goldstein said. "Without it, they'd still be renting. If the goal of the program was to position people to obtain home ownership, this did it. And it did effectively."

The importance of looking at rental markets to understand trends in home ownership is obvious, since an aspirational homeowner is most often a current renter.

In a city where 43.6% of residents are Black and 15.2% are Hispanic, racial disparities between renters and homeowners have a major impact on the composition of Philadelphia's housing market as a whole.

The table below shows home ownership rates among white, Black and Hispanic residents in Philadelphia based on statistics from five-year samples from the American Communities Survey between 2015-2019. The U.S. Census bureau has warned that its one-year sample from 2020 is unreliable due to data collection issues during the pandemic.

| Race/Ethnicity | Home Owners | Renters | % Home Owners |

| White | 158,315 | 112,103 | 58.5% |

| Black | 119,745 | 127,774 | 48.4% |

| Hispanic | 30,786 | 38,311 | 44.6% |

The second table shows the median household income in Philadelphia among white, Black and Hispanic residents.

| Race/Ethnicity | Median Household Income |

| White | $61,943 |

| Black | $35,002 |

| Hispanic | $32,912 |

| All Households | $45,927 |

Sizable disparities exist in homeownership rates and income levels in Philadelphia, meaning rising rents and home prices are more of a burden on minorities who are getting squeezed by both markets. Out of the 30 largest cities in the U.S., Philadelphia's median household income ranks 28th, ahead of only Memphis and Detroit.

"With the price rises, we're really lopping off large sectors of the market at this point, and differentially so for people of color than for white people just because the incomes are lower," Goldstein said.

In the Philadelphia metro area, which includes Camden and Wilmington, the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment reached $1,679 in February, a 6.1% increase over the previous year. A two-bedroom apartment rose to approximately $1,950, an annual increase of nearly 5.5%, according to data from Realtor.com.

There are certainly better deals to be found on rental properties in areas scattered throughout Philadelphia neighborhoods, although anecdotal reports from apartment hunters and tenants who have recently renewed leases reflect greater-than-usual rent increases in 2022.

Data from Apartment List, an online marketplace for rental listings, reported median rents in Philadelphia at $1,097 for a one-bedroom and $1,272 for a two bedroom at the end of March. Year-over-year rent growth of 11.2% in Philadelphia ranked 77th among the nation's 100 largest cities, while rents in Philadelphia are up 6.8% since the start of the pandemic in March 2020. Apartment List's methodology was revised this year to better account for luxury bias and has switched to using transacted rent prices instead of list prices in order to calculate estimates of rental rate growth.

Philadelphia's rent still pales in comparison to places like New York, Boston and Washington, D.C., but the effects of rental prices on residents are relative to the demographics of each city. All marginal increases in rent fundamentally erode savings that are needed to become a home owner, if that's a personal or family goal.

Without the money required for down payment and closing costs, some renters who wish to buy will remain stuck in their current situations even if a mortgage would cost them less than they pay in rent on a monthly basis.

"There are a lot of renters who are sustainably paying $800-$1,200 per month. You could back into a mortgage that would allow you to sustain the same range," Goldstein said. "It's enough to get you into the lower half of home prices in Philadelphia. This is why a grant program like Philly First Home is so important. If that's as much as you can afford, you probably don't have a lot saved in the bank to buy a home."

Research on Philadelphia's growth in recent years has shown that the majority of new jobs created in the city are low-wage positions that pay $35,000 or less, while middle-wage growth has remained essentially flat. The jobs that disappeared during the pandemic were mostly in low-wage sectors, affecting minority residents and women the most amid rising housing costs.

"Philadelphia only has mediocre economic growth, and that is a problem," Ferreira said. "But even mediocre growth can lead to high house prices and rents if we do not radically increase housing supply."

To outsiders from bigger, higher-growth cities, the cost of housing in Philadelphia appears both affordable and inviting by comparison. It's one of the reasons the city has become so attractive to transplant remote workers, who play a role in driving up the region's real estate prices.

For sale sign on home on Terrace Street near Shurs Lane in Manayunk.

Quality of life issues aside, most Philadelphia residents are flat-out too cost-burdened to become home owners as they feel the effects of inflation and incremental rises in rent. The income problem turns what could be an affordable city to buy a home into one where scarcity keeps working families drifting out of reach of home ownership while they pay their landlords more.

"When you think about what you can get here, the average first-time home buyer's mortgage payment is ranging anywhere between $1,000-$1,500 per month," Whitaker said. "To rent a three- to four-bedroom home, you're most likely starting between $1,400-$1,700 per month. For a lot of people, it makes more sense to own if they can do it."

For people of color, that's perennially a big "if" in Philadelphia and other cities that have been long-term homes.

A recent report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition underscores how racial disparities in mortgage lending have persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic, making it harder for people of color to access conventional loans in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods where they may be able and interested in buying houses.

Almost 60% of Black home purchase applications in the United States are through federally-backed FHA, VA and RHS loan programs. For Hispanic Americans, it's about 50%.

These insured mortgages usually reduce the size of a down payment, qualify people with lower credit scores and permit higher debt-to-income and loan-to-value ratios. They are an invaluable resource for many buyers, but they come with competitive drawbacks and additional costs that drain wealth in the short- and long-term.

Home sellers sometimes are reluctant to take offers from buyers who are pre-approved for FHA loans, for example, since the program has stricter appraisal guidelines that can depress the value of a property and may require more repairs in order to complete a sale. The loans may also face administrative delays that put buyers at a disadvantage in fast-moving markets.

Most importantly, FHA loans are often perceived to be riskier. The borrower will need to pay higher interest rates and an insurance premium for the life of the loan in order to become a home owner.

"We find, more and more, that redlining and segregation that existed throughout the late 19th century and into the 20th century has shaped a lot of these communities in ways that are still being perpetuated today," said Jason Richardson, NCRC's director of research.

One of the most notable features of the current market for mortgage lending is that nearly 70% of loans in the U.S. are now originated by non-bank lenders, as opposed to large banks that may later purchase these loans from the brokerages. The key differences occur on the regulatory and retail side of the industry.

"The banks are covered by the Community Reinvestment Act, so they're examined periodically to make sure they're not excluding Low-Moderate Income neighborhoods or people," Richardson said. "Today, nobody is looking at mortgage companies the same way, except in a few select states."

When people of color apply for conventional loans from banks and other private mortgage lenders, they are more likely than white people to have their applications denied. Banks that focus on mortgage origination are wary of FHA loans because they don't want to have to buy them back if they default, as happened during the Great Recession, Richardson explained.

If large banks avoid FHA loans, and more than half of Black and Hispanic buyers rely on these loans, then the options for these buyers become more starkly limited to mortgage brokerages that are driven by commissioned salespeople, who already dominate the mortgage space. The commission structure incentivizes seeking out the largest loans and the easiest to close, which disadvantages borrowers who are less competitive in a sellers market, or who are up against investors purchasing multiple properties.

"Sellers can pick the best offer and there's really not much you can do about that," Richardson said. "They can't discriminate for a variety of things, but they're still allowed to judge the quality of the offer based on how it will close."

An analysis by Reveal News, independently reviewed and confirmed by the Associated Press, specifically identified Philadelphia as among the worst cities for Black residents to obtain conventional mortgages, which were denied at nearly three times the rate seen among white borrowers during the two-year period of 2015-2016.

There were more than 150 lenders that made loans to buyers getting Philly First Home grants, but 13 lenders accounted for more than half of those loans. The city did not provide specific data on lenders, but it appears that a large share of the mortgages obtained by Philly First Home buyers were not conventional loans. The grant money not only made buying homes feasible for them, but likely enabled them to make more competitive offers despite the category of loans they obtained.

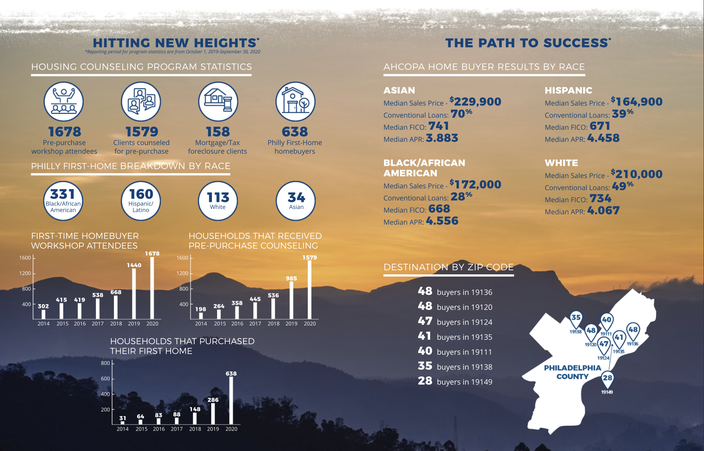

Below is a snapshot of the loan breakdown among a sample of 638 Philly First Home clients who were counseled by the Affordable Housing Centers of Philadelphia. Only 28% of Black participants and 39% of Hispanic participants took out conventional loans, compared to 49% of white buyers and 70% of Asian buyers.

(Note: This graphic was created by Affordable Housing Centers of Philadelphia)

Larger reviews of disparities in federal mortgage data have consistently demonstrated the barriers people of color face in obtaining conventional home loans. The lending industry evades this criticism by resisting public disclosure relating to the use of credit reports and other data that could identify discriminatory practices. The argument is that withholding this information is a matter of consumer privacy.

"The industry is relentlessly pushing to keep that private," Richardson said. "Regulators do have (that information) now, so there is that kind of security. But I think it could be safely shared, even if it was anonymized."

One of the weaknesses of emphasizing credit reports for home loans is that they historically do not include a record of rent, utility and cell phone bill payments, unless a person happens to miss these payments and they become debt. In that case, the individual's credit score will be harmed. If the same person diligently pays bills and demonstrates some measure of creditworthiness, that history may only be factored in if the individual independently reports the information to a credit bureau.

Richardson is encouraged by the credit reporting industry's growing acceptance of alternative data, such as rent history. In the years to come, he believes adoption of this data will become more mainstream among credit bureaus and government-sponsored enterprises, like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which help extend capital to lenders in the housing market.

Those who might look at today's disparities and suggest that mortgage lenders serve fewer people of color in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the sub-prime crisis are misinterpreting the causes and effects of the financial collapse.

The Great Recession that followed the housing crash threw minority communities into unemployment and foreclosure, leading to wider financial industry reforms such as the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. Predatory lending was an exploitative means to the end of profiting from exotic loans that ultimately dispossessed people, with little to no accountability.

"The loss of wealth that would have been gained by Black and minority households prior to that housing crisis has only been exacerbated," said Josh Devine, NCRC's director of racial economic equity. "These groups were disproportionately affected by foreclosure, which has a generational impact. In many cases, this continues to be challenging in terms of finding affordable mortgage credit programs to support these families who are looking for opportunities to buy a home."

NCRC's analysis shows that the gap in homeownership rates for Black and white families is now near its highest point in 120 years. The long-term effects of the housing crash continue to deprive people of color of the benefits they could have reaped from sustained home ownership.

"I don't think it's really well understood by a lot of folks that the years you own a home are the biggest determining factor in the wealth that you have later in life," Richardson said. "The fact that Black, Hispanic and some other groups are habitually either steered away from, discouraged or have flat-out been locked out of home purchasing means that they have less wealth overall, over time. When we get into periods like this, when interest rates go down and refinancing becomes a great option, they are disproportionately unable to take advantage of that the way other groups can."

The basic problem with mortgage education is that it's "deadly boring" for most people, Richardson added, and while mortgage tech companies with accessible digital platforms can help even the playing field for consumers, the workings of the industry are bewildering – frequently and quietly by design.

"Mortgage policy and how mortgages are provisioned is a key part of how neighborhoods function over time and how families build wealth," Richardson said. "By creating a system that is so complicated, very few people really understand it. That makes it difficult to make changes to it and get people to really care about it the way they should. I don't think it's visible to most people how big of a hand this kind of thing has in shaping their daily lives."

In Philadelphia, one of the cruel ironies of the housing market is that there are plenty of homes for sale that lower-income families could conceivably afford. The properties may need work and they may be in troubled neighborhoods, but they are out there.

"We have housing stock that you can buy in some areas of the city for $90,000 – which is unheard of – and you can find houses for up to $190,000," PHDC president Dave Thomas said. "Both of those are scenarios where people can probably afford that mortgage more so than the rent. There are unexpected costs that you come across as a homeowner that you don't as a renter, but when you have a $1,300 fixed mortgage, your monthly payment doesn't change unless you make changes. When you're renting, (rent payments increase) the longer you stay."

One challenge is that banks are not making enough small mortgages available, Goldstein said.

"If you want to buy a $100,000 house, maybe you need a $90,000 or $95,000 loan. There just aren't that many being made, and this becomes a challenge for people who are trying to get in at that lower price stratum," Goldstein said. "Where do they get the money? If you're someone trying to buy a $100,000 house, you don't have it in the bank. Those homes will go to investors who scarf them up and take them out of range for a more modest-income person."

When individual buyers are unable to buy properties in this low price range, those homes instead are often bought by investors, who may fix them up just to rent them out in a market that incentivizes doing so. Alternatively, renovated houses can be flipped by investors at a profit, especially during times of low supply. This drives up home values, property taxes and often rents in these neighborhoods.

A mortgage loan officer from a large national bank, who spoke to PhillyVoice but declined to be named, suggested that smaller mortgages are less common, in part, because seller assists are less common due to low home supply. With buyer demand as high as it is, sellers don't have the incentive to bend over backwards to complete a transaction. Buyers who can't make the process as smooth and as profitable as possible for sellers will lose out to other buyers who are willing and able to pay more, or who aren't as concerned about home inspections.

When it comes to low-priced homes, investors have more flexibility to spend and fully expect to put more resources into fixing up properties that need work. Lower income buyers of these cheaper homes can hardly cover the closing costs, which are comparatively expensive in Philadelphia, and they often need other forms of assistance such as grants.

The sellers of low-value homes likely won't want to risk getting derailed by problems that an appraisal might find when a buyer is using an FHA loan.

"Why accept that when they can just accept someone else?" the loan officer said. "It's really hurt people who don't have the money saved. The mortgage loan officer is not going to turn down a loan or say no. It's just that the buyer doesn't have the necessary capital for a competitive offer."

At Wells Fargo, Ernest Campbell is the Philadelphia market's retail mortgage manager. He argued that philanthropic investments in non-profits should be expanded and used to match pre-approved, low-income residents with homes that need renovations, giving them a choice in the designs of the homes they will purchase. He cautioned that the cheapest properties in Philadelphia – those that need expensive repairs – are difficult investments for people who already lack resources.

"Typically, when I see a house at the $90,000 price point, the first thing I think is, 'What's wrong with it?'" Campbell said. "What you don't know is the state of those homes. Will they pass an inspection? Will they meet FHA requirements? Are they inhabitable? Do they have health and safety issues? A lot of these homes need work, and you can't get conventional or FHA financing unless you're doing a renovation loan to bring the house to code."

Mortgage brokers simply stand to benefit more from working with investors in neighborhoods with cheap homes, compared to a person buying a single home. An investor who wants to buy three properties is going to yield a higher commission for the broker than a low-income, first-time buyer who's barely affording a home in the $100,000-$150,000 range, for example.

"What's the incentive for the mortgage broker to make a $100,000 loan if they could instead work the same amount of time, or less, and make a $300,000 loan to an investor, or a home owner who has a lot of equity?" said Richardson, who previously worked as a mortgage broker.

Unlike the era of subprime mortgages, the retail side of the mortgage industry is no longer courting low-income buyers with the same tenacity, in part because regulations were put in place to prevent past abuses. The flip side is that some capable and qualified buyers are not as well served.

"If a borrower wants to buy a house in Philly for $100,000 and they go seeking somebody to make the loan, they should be able to find somebody, but it's not going to be aggressively marketed to them," Richardson said.

Community development corporations – also know as CDCs – and community development financial institutions – or CDFIs – are built to make secure loans to low-income home buyers by leveraging public and private capital, but their successes are isolated because they lack the scale of large, private lenders and the financial flexibility of investors.

In big cities, cheap homes and vacant lots are a feeding frenzy for investors because they have the resources to turn these properties around quickly and generate profits.

A Washington Post analysis of 40 metro areas in the U.S. found that investors had bought almost one of every seven homes for sale in these communities last year. In the Philadelphia metro area, 15% of homes were purchased by investors in 2021, a 4% increase compared to 2015.

In the 19121 ZIP code in North Philadelphia, about 35% of the homes purchased in 2021 were sold to investors. That percentage is as much as 44% in other parts of North Philly and West Philly.

Last year, across all 40 metro areas in the U.S., investors purchased 30% of homes sold in neighborhoods where the majority of residents are Black, compared with 12% in other ZIP codes.

The data on investor activity comes from Redfin, and Philadelphia ranked just outside the nation's top 25 markets being targeted by investors.

Even so, with the rate of home-price inflation in the U.S., many investors are now buying up a growing share of mid- and high-priced homes, too. This is more of a threat to the type of buyer who may be shopping for a property in the $150,000-$250,000 range using a Philly First Home grant, versus homes that are in greater disrepair or in highly distressed areas.

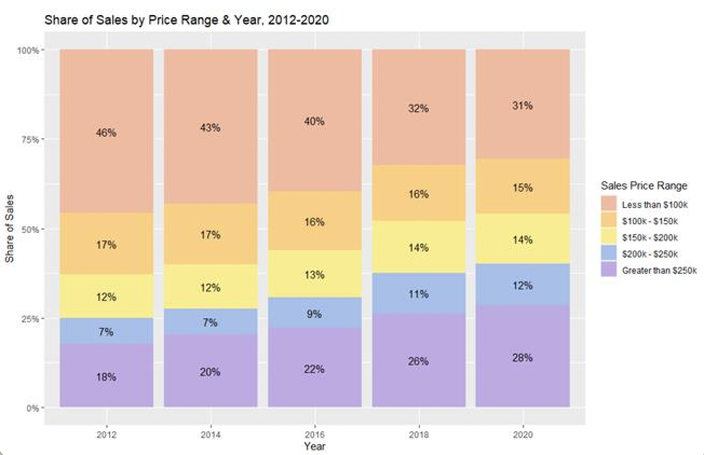

It's also an indication that a large number of Philadelphia's cheapest homes likely already have been purchased by investors during the last decade, which saw a decline in the share of homes sold under $100,000 from 46% in 2012 to 31% in 2020, according to data shared by Reinvestment Fund.

(Note: This chart was created by the Reinvestment Fund)

Investors could be large institutions, such as corporations and private equity firms, small or mid-size companies, "mom and pop" landlords, or wealthy individuals. They are not all created equally and their roles in transforming neighborhoods speak to the recurring theme of an inadequate supply of homes, especially single-family properties for owner-occupancy in cities like Philadelphia. Investors may convert these properties into rentals and compound the issue, but the existing lack of homes in a given area is a core piece of what makes that particular market attractive to an investor in the first place.

A common complaint about investors in Philadelphia is that they are perceived to do hasty work using low-cost materials that don't preserve the character and history of the city's neighborhoods. These qualitative judgments are not insignificant – community groups often exert pressure on home renovators to conform with surrounding aesthetics – but there are more vital concerns about how attentive and fair new landlords will be, how durable and well-maintained their properties will be, and what the emphasis on single-family rentals does to neighborhood rates of home ownership.

Another blemish on investors is that some choose to buy up vacant lots and crumbling homes in poor neighborhoods just to sit on them until other investment activity increases their values. In Philadelphia, certain tax reform advocates want to see this behavior discouraged by instituting a land-value tax that would make property taxation more equitable.

During the pandemic, institutional investors often have been blamed at the national level for driving up the prices of single-family homes and competing with regular buyers, who actually want to live in them as their primary residences.

Visceral distaste toward Wall Street speaks to longstanding public grievances about staggering inequality that extends far beyond the housing market, a particularly sensitive issue due to the lion's share it represents in the average American budget. The actual share of single-family homes owned by institutional investors in the U.S., though growing quickly and diversifying in property type, still remains fairly small in absolute terms.

Most often, investor purchases of single-family homes are made by smaller companies and individuals seeking second homes as rentals or vacation pads. Institutional investors focus on distressed, supply-constrained areas where there are place-based tax incentives to stimulate activity. The demand for home ownership appears comparatively low in these urban areas, either because residents can't afford the homes or because the available properties are in too bad of shape.

In Philadelphia, institutional investors are most in competition with smaller home-flippers and aspiring landlords, all vying for properties in neighborhoods that are gentrifying at different paces.

The exact pressure that institutional investors add in today's market is their depletion of home supply precisely in parts of the United States where lower-income buyers might be on the fringe of affording home ownership. These buyers don't have the resources to compete with mega-corporations that make all-cash offers or get loans with lower interest rates to finance multiple properties using rental revenue.

When housing supply is low, rising mortgage rates also pose a particular threat to home ownership because investors of all kinds can withstand the higher expenses, while many regular buyers must back out of the running or further limit the price ranges of homes they can afford.

In the event that home prices start to come down this year or next in response to higher mortgage rates, it may end up fueling more investor purchases relative to other buyers with harder financial constraints.

The notion that investor-bought properties might create more affordable neighborhood rentals is often belied by the investors' transparent motivation to buy in places where they know they'll be able to jack up rents. Invitation Homes, for example, one of the nation's largest owners of single-family rentals, openly tells its investors that it operates in markets with "high rent-growth potential" and low expectation of new home supply, with a heavy presence in the Atlanta metropolitan area.

Inherently, any shortage of home inventory makes real estate a compelling investment strategy for speculators.

The ways in which property investors distort prices in hot and distressed markets are still being studied, and because housing markets are cyclical, there also is a belief that investors can play an economically important role in setting a permanent floor of demand in the the event of a downturn. That's what happened when investors bought up foreclosed homes during the Great Recession, followed by a decade of curtailed new home construction that underlies today's predicament.

The core issue for aspiring home owners today is that so many investment properties become single-family rentals. The best-case scenario is that this may help deliver enough supply to create affordability for a critical market of renters. The worst-case scenario is high levels of neighborhood displacement.

Until home inventory for owner-occupancy rises, the present trajectory will greatly limit the most important pathway people have to financial equity and long-term wealth.

"While investors always have a role in any community, when they crowd out owner-occupants, which we hear from many sources, there is an imbalance in the market," Richardson said.

First-time home buyers intrigued by single-family properties in neighborhoods that are targeted by investors may need to weigh more risks than they would in Philadelphia's less volatile middle neighborhoods.

If a buyer in Brewerytown lines up a Philly First Home grant, for example, they're possibly betting on staying in that home for 15 years to cover the period of the city's lien on the property. The increased values of nearby homes that are renovated by investors will raise property taxes, accruing a cost beyond the mortgage that will be hard to absorb if a home owner's income does not increase proportionately.

Depending on how much work this hypothetical buyer puts in to the home – assuming some is needed – the home's value should also increase with those around it and the owner will be free to sell at any time. The owner may even be able to do so at a margin much greater than the cost of paying back the grant amount, before 15 years have elapsed.

Of course, not everybody wants to buy a home with the primary consideration of selling it, a point that sounds more obvious than it is in today's exuberant, investment-driven market. Most aspiring first-time home buyers, the people now having the hardest time buying houses, just want comfortable places to live and raise families as they build equity, first and foremost.

For those wary of future tax increases, Philadelphia has relief programs such as the homestead exemption, LOOP and a mechanism to appeal a high property-tax assessment, which could possibly rectify an unreasonable jump in cost. There's no guarantee the city makes a requested adjustment, however. (This is an issue that will soon come roaring back in Philadelphia as the city prepares to release its first property value reassessments in two years, ending a hiatus that covered a period of sharp home price growth).