April 27, 2021

Thom Carroll/for PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/for PhillyVoice

Middle-wage jobs in Philadelphia — those that pay between $18.61 to $27.92 per hour — did not keep pace with overall job growth in the city leading up to the coronavirus pandemic. The recovery from COVID-19 now will present deeper challenges to stimulate the return of these vital positions across Philadelphia's economy.

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on Philadelphia's economy and the United States as a whole could take several years to become fully apparent, as lasting trends take hold during an extended recovery period.

But new research from Pew Charitable Trusts shows that Philadelphia's progress in creating middle-wage jobs had already flatlined in the five years leading up to the economic turmoil caused by COVID-19.

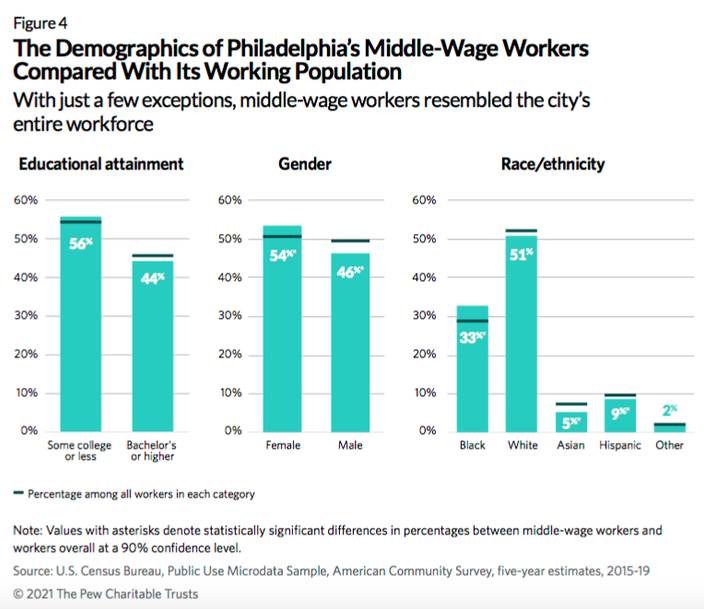

In a city where roughly a quarter of the population is impoverished, middle-wage jobs offer a vital pathway to an improved standard of living — even for those without college degrees. Yet, increasingly these jobs are held by those who are college-educated.

Pew looked at the most recent census data to examine pre-pandemic employment trends in Philadelphia between 2015 and 2019. Middle-wage jobs, defined below, comprise nearly a quarter of the city's workforce:

In the census data, the median wage among civilians who worked in Philadelphia (including residents and nonresidents) was $23.26 per hour (in 2019 dollars). Based on that finding, Pew defined middle-wage positions as those paying plus or minus 20% of that median (middle) wage, or from $18.61 to $27.92 per hour. (The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has estimated that a living wage in Philadelphia for a household of two adults, one of whom is employed, and one child is $24.02 per hour.) By Pew’s definition, about 145,000 people working in Philadelphia, or 23% of the workforce, held middle-wage jobs during this period before the pandemic.

The study found a number of notable shifts since the last period examined in the wake of the Great Recession from 2009-2013. Though the number of people working in Philadelphia has grown in recent years, the number of people with middle-wage jobs has not significantly changed. It stands at just under a quarter of the city's workforce.

Comparing the 2009-2013 period to the 2015-2019 timeframe, Philadelphia's workforce grew by about 25,000 people, or roughly 4%. The number of people earning middle-wage jobs increased by only about 400 people. That's less than 1%.

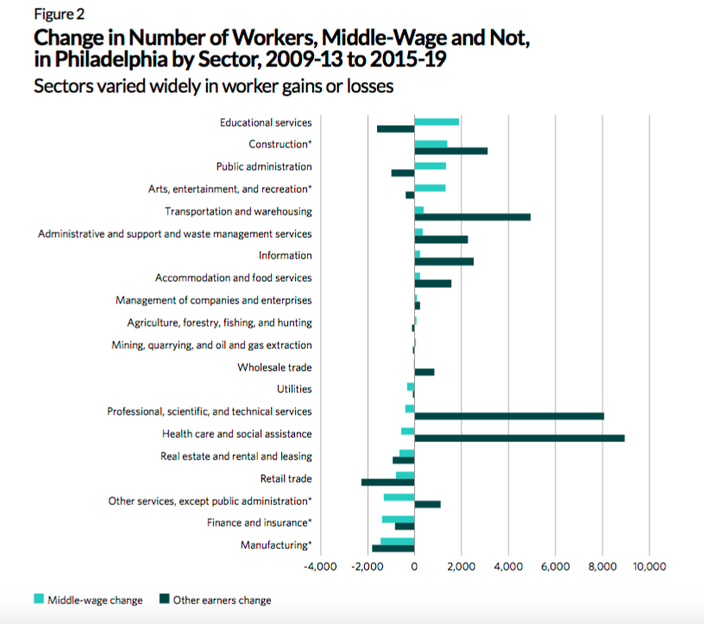

The majority of Philadelphia's middle-wage workers are employed in health care and social assistance, educational services and public administration — three fields that primarily employ women in middle-wage roles. Men earning middle-wages make up the large majority in transportation and warehousing, manufacturing and construction.

Pre-pandemic changes in various sectors show that middle-wage jobs were lost in a number of industries during the course of the last decade, including retail, finance, insurance and manufacturing. In educational services, nearly 2,000 middle-wage jobs were added, while other earners in the field saw a sharp decline in positions.

In some cases, such as manufacturing, the downward trend in middle-wage earners mirrored losses among all wages earners in that industry. In other cases, such as the large health care and social assistance sector, middle-wage jobs declined while employment for other wage earners expanded significantly. The share of middle-wage workers in this sector — about 23% — is roughly equal to the share of middle wage workers in the city's economy as a whole.

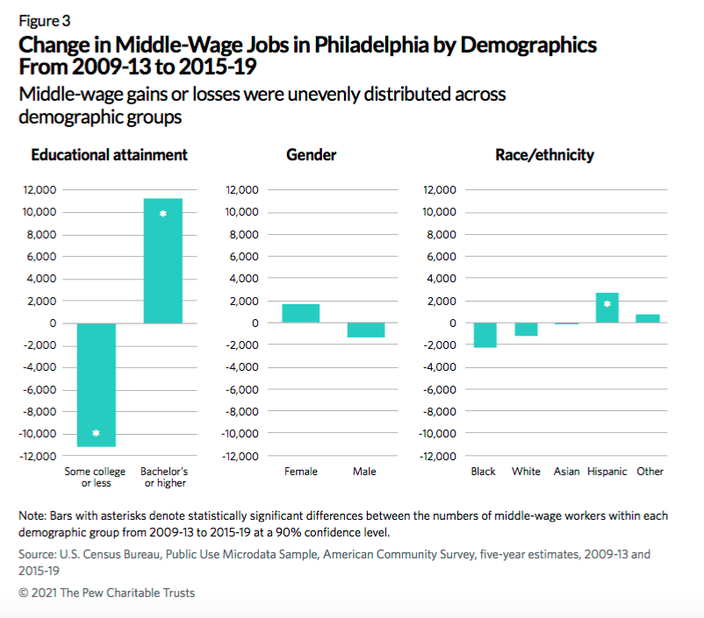

Middle-wage opportunities also have increased for women, while men have seen their share of these positions diminish. Hispanic workers in Philadelphia represented the largest growth in middle wage earners before the pandemic.

For the most part, the demographics of Philadelphia's middle-wage workers mirrored the city's workforce as a whole.

On April 30, Pew will hold a live webcast in partnership with the Philadelphia Inquirer to discuss and contextualize the city's road to recovery for small businesses and jobs in the wake of the pandemic.

"The preservation and expansion of middle-wage positions will be a key factor as policymakers consider the city’s post-pandemic economic future," Pew researchers concluded in their report.

Source/Pew Charitable Trusts

Source/Pew Charitable Trusts Source/Pew Charitable Trusts

Source/Pew Charitable Trusts Source/Pew Charitable Trusts

Source/Pew Charitable Trusts