July 12, 2024

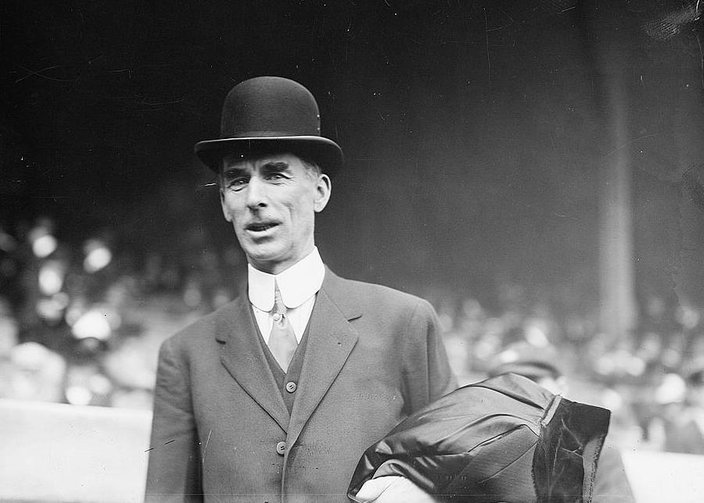

George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

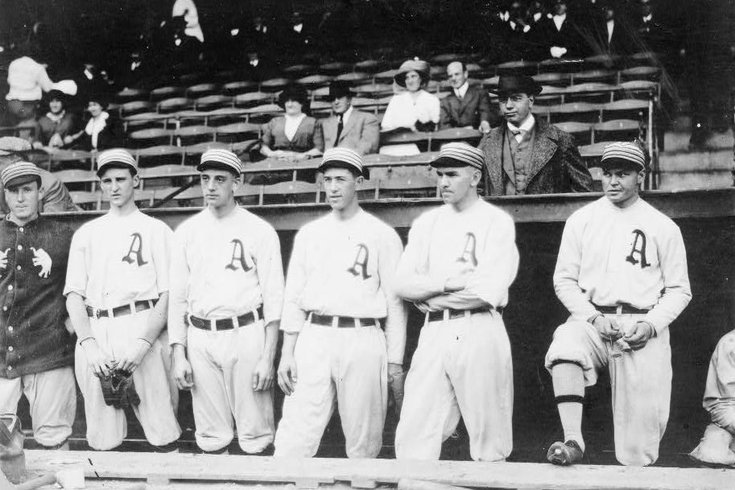

The Athletics left Philadelphia for Kansas City after the 1954 season after the Mack family sold the franchise, a move spurred by family divisions, financial hardships and baseball's changing economic landscape. The photo above, taken in April 1914, shows Billy Orr, Herb Pennock, Weldon Wyckoff, Joe Bush, Bob Shawkey and Amos Strunk (left to right). Pennock, a pitcher, was among numerous Hall of Fame players to play for the A's in Philly.

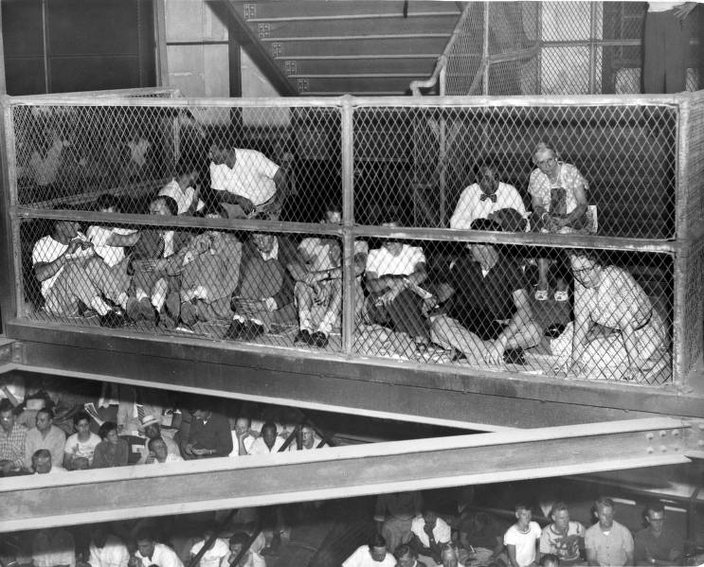

Hours before the Philadelphia Athletics were to play at Shibe Park on Aug, 5, 1952, throngs of people filled the streets outside the ballpark at 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue.

On this night, Bobby Shantz, a diminutive lefty from Pottstown, was going for his 20th win – with nearly two months to play in the season. No A's pitcher had won 20 games that early since the great Lefty Grove in 1931.

More than 35,000 people came out to see Shantz pitch. It was the largest crowd the A's had drawn since July 1948, when they were battling Cleveland for the American League lead.

Thousands of fans were turned away by police officers before they even reached the ballpark, including John Rossi, a young Phillies fan who had tried to go with his uncle, a longtime A's fan.

"We were approaching, and a cop stops us and he waves at us," recalled Rossi, 88, who grew up in Olney. "He said, 'Where are you going?' And my uncle says, 'We're going to the ballgame.' (The officer replied), 'Forget about it, the game's sold out.' So, we had to turn around and go back."

Those fortunate to have tickets had to sit through a 71-minute rain delay before the game even started. But Shantz made the wait worthwhile. He pitched a complete game, beating the Boston Red Sox, 5-3.

In many ways, that night was the A's last hurrah in Philadelphia. Shantz went on to win the American League's Most Valuable Player award, finishing the season 24-7 with a 2.48 ERA. The A's finished fourth in the eight-team American League – as high as they had in decades.

Once the final out was secured, the fans rushed the field. Shantz bolted for the dugout, but stumbled upon reaching its steps. Had manager Jimmy Dykes, pitcher Bobo Newsom and announcer Pete Byron not caught him, he'd had have fallen down the dugout steps and onto the concrete runway.

In the stands, Bruce Kuklick was pulled through the crowd by his father as they left their obstructed-view seats down the third-base line. No one had left early, Kuklick, 83, said.

"As my memory goes, it was huge – the biggest crowd I had ever seen in my life," said Kuklick, a retired history professor at the University of Pennsylvania who wrote a book on Shibe Park, "To Every Thing A Season." "I was 10 or 11. I was holding my dad's hand – he took me and (dragged) me through this crowd. Everybody is cheering and yelling and everything like that."

A's fans crammed into Shibe Park in 1952 to see Bobby Shantz pitch. The Pottstown native won the American League MVP award by finishing 24-7 with a 2.48 ERA. He might have won 25 games had a pitched ball not broken his hand late in the season.

All season, A's fans had turned out when Shantz was pitching. But when he wasn't on the mound, attendance was meager. The A's averaged nearly 18,000 fans during Shantz's 17 starts at Shibe; they averaged fewer than 8,000 during their other home games. Shantz's starts accounted for about 44% of the A's home gate.

"It was one of the great hopes of the franchise that Shantz would be able to keep the team solvent and in Philadelphia," Kuklick said.

But a pitched ball broke Shantz's wrist late that season, and he battled injuries in subsequent years.

"He just struggled the last two years here in Philadelphia," Rossi said. "And it looked like the collapse of Shantz was a hint of what was going to happen to the A's."

Two years after Shantz, the A's left Philadelphia for Kansas City, Missouri, a move spurred by ownership squabbles, dwindling attendance and baseball's changing economics. When they played their final home game in North Philly on a dreary afternoon on Sunday, Sept. 19, 1954, fewer than 2,000 fans came out. They lost, 4-2.

Seventy years later, the A's again are on the move. This time, they're fleeing Oakland, having departed Kansas City decades ago. It's the third time the franchise has moved – more than any in modern baseball history. Once again, they're leaving behind a community of fans, and a ton of history.

Nellie Fox is tagged out by Boston Red Sox catcher Birdie Tebbetts during a game at Shibe Park in 1949. Connie Mack traded Fox to the Chicago White Sox after the season. Fox was 21 and had not established himself, but he went on to make the Hall of Fame.

The A's spent 54 seasons in Philadelphia. The team was one of the original American League clubs, formed in 1901 by Benjamin Shibe, Connie Mack and two sportswriters. In most years, the A's could be found in one of two places – near the top of the AL standings, or near the basement. There wasn't much mediocrity.

The A's – back in town this weekend to play the Phillies – won nine AL pennants and five World Series while in Philly. Numerous Hall of Famers played significant portions of their careers for the A's, including Eddie Plank, Eddie Collins, Frank "Home Run" Baker, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane and Grove. Ty Cobb, Nap Lajoie and Tris Speaker all briefly suited up, too.

The team also finished last 18 times, and next-to-last four times. And most of those losing seasons occurred during their final two decades at Shibe Park, which was renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953.

But in 1950, the A's expected to regain their glory. In the three previous years, the A's had stayed in the thick of the pennant race before faltering down the stretch. Mack, now 87 and managing his 50th season, predicted the team would win the AL for the first time since 1931.

The season proved an utter disaster. Instead of celebrating Mack's legacy, it brought greater scrutiny to his performance as a manager and executive.

"I think up until that time, people had still thought that Connie Mack was this 'Grand Old Man of Baseball,' as he was called," Kuklick said. "He was the symbol of the city and the symbol of this great A's dynasty that had carried along for half a century. ... It was quite sad, but he lost a lot of public and fan support in 1950. Even though the team got a little better in (subsequent years), it never really recovered from the disaster of 1950."

The A's lost 102 games, finishing 46 games behind the first-place New York Yankees. The team had budgeted for 800,000 fans – and hoped to draw 1 million – but the season's total attendance was a mere 309,805. Perhaps most consequentially, divisions within the Mack family, whose ownership of the A's was split among several family members, spilled into the public.

Mack's oldest sons, Roy and Earle, did not get along. Once, when Earle had moved into a suite at the ballpark, his brother had the water turned off so he couldn't bathe or use the toilet. But they had a common foe in their half-brother, Connie Mack Jr., who was born to Connie Mack Sr.'s second wife.

The brothers entered into an agreement that would allow Roy and Earle to buy the stock of Connie Mack Jr. and members of the Shibe family – if they could raise the money within 30 days. Otherwise, Connie could buy them out. Roy and Earle obtained the funds by mortgaging Shibe Park, a move that hampered the A's ability to stay solvent in the years that followed.

Meanwhile, the Phillies – a longtime laughingstock – made their first World Series appearance in 35 years in 1950. The "Whiz Kids" had captured the heart of the city, drawing a franchise-record 1.2 million fans.

"Everybody fell in love with them," said Ted Taylor, 83, who co-founded the former Philadelphia A's Historical Society and penned several books on the team. "... And that impacted the A's as much as anything else. Because they were having their worst season in decades in 1950 – Connie Mack's 50th anniversary year. That just blew up on them."

Following the season, Roy and Earle Mack forced their father from the dugout. By that point, criticism of his moves as a strategist and as a baseball executive had mounted. (Among his more infamous deals were trades that sent packing Hall of Famers George Kell and Nellie Fox before they hit their strides as big leaguers).

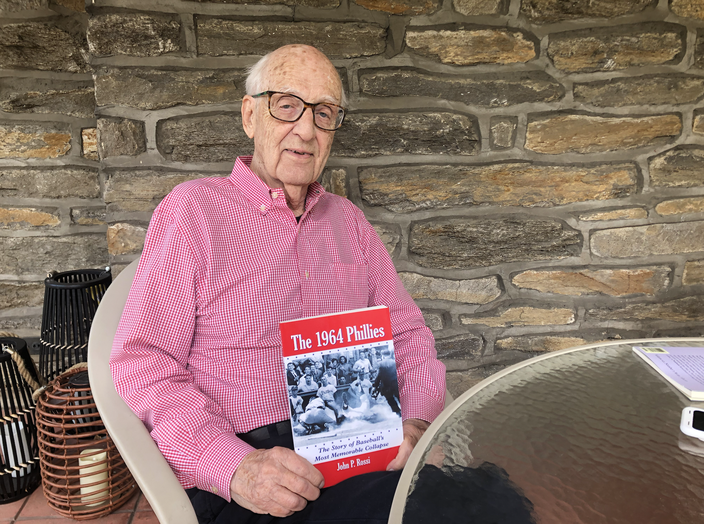

John Rossi, a retired history professor at La Salle University, has written several books on baseball, including one on the 1964 Phillies. He and his uncle tried to see Bobby Shantz win his 20th game for the A's in 1952, but tickets had sold out before they arrived at Shibe Park.

But changing the manager had come too late.

Connie Mack had not kept pace with changes in baseball, said Rossi, a retired La Salle University professor who taught a course on baseball history and has written several books on the sport, including one on the 1964 Phillies' collapse.

Whereas other teams built expansive minor league systems, Mack long relied on his connections in the sport to sell him the contracts of talented players, Rossi said. And unlike other owners, the Macks had gained their wealth through baseball, not other business ventures.

"Baseball boomed after the war, and the business side of things became very important – more important than it had been before," Rossi said. The A's were "really being run like a private family thing. ... They didn't keep up with the changes in baseball."

The Phillies continued to play to much larger crowds than the A's during the 1950s.

Steve MacKenzie, a Phillies fan who grew up in North Philly's Swamppoodle neighborhood, could see Shibe Park's lights from the end of his street. His friend's dad worked at the ballpark and would sneak the boys into the bleachers during A's games. But he couldn't do it for Phillies games, because they drew bigger crowds.

"It was a just a different atmosphere when the A's played," said MacKenzie, 76, who owns Knuckleball Sports Cards in Horsham. "It was just a quiet event. Fans would cheer and stuff, but the Phillies fans were much louder – many more, too, which added to the noise. The A's were just dwindling in attendance, and that's probably what sparked Kansas City."

Shibe Park, shown in 1940, was the home of the Philadelphia Athletics from 1909 to 1954, when the franchise moved to Kansas City. The ballpark, renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953, also housed the Phillies from 1938 to 1970.

There had been reports that the Athletics could be sold and moved at varying points during the early 1950s. But that possibility increasingly appeared more likely as the 1954 season progressed.

"It was kind of like the handwriting on the wall," MacKenzie recalled.

By July, the A's were bumbling toward another last-place finish, and attendance was dismal.

At one point that season, Taylor was at an A's game with his mom. A foul ball landed three sections from where they were sitting in the upper deck, but he had no trouble retrieving the ball.

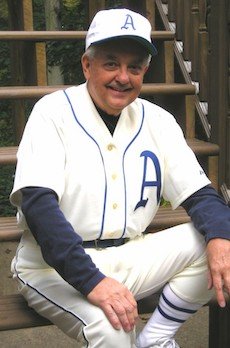

Ted Taylor helped found the former Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in the 1990s. Above, he wears a 'Throw Back the Clock' uniform the Oakland A's gave him during a visit to the Oakland Coliseum in the mid-1990s.

"There couldn't have been 500 people in the whole stadium," Taylor said. "That's the only baseball I ever got."

With the franchise in financial trouble, the Macks turned to the city for help. To ensure the team's future in Philly, the club needed to draw at least 600,000 fans. Otherwise, the Macks would be forced to sell or relocate it.

One city councilman proposed the city subsidize the A's and the Phillies by buying tickets to be distributed to children who excelled in school. But Mayor Joseph Clark wasn't in favor of using public money to support sports franchises, calling it "creeping socialism." Instead, he organized a Save the A's Committee filled with 100-plus people and tasked it with finding a solution to keeping the A's above water.

Various suggestions were tossed out on the day the committee was revealed. Among them: The city should turn the park across from Connie Mack Stadium into a parking lot. More policing was needed to protect cars parked on the streets during games. The team should broadcast all of its games on television, and ask each viewer to purchase $10 in tickets.

The committee ultimately was of little help. It found little support for the A's among Philadelphia's business community, and its attempts to stir up fan interest fell flat. The A's barely drew 300,000 fans – the worst attendance in baseball.

Though the fans didn't show up to the ballpark, they flooded the city's newspapers with letters. Some tried to rally the city around the A's.

"I am writing to ask the people of Philadelphia to come out and support the A's," a fan from Media, Delaware County, wrote on July 8. "They should really be ashamed of themselves. They want a modern, forward-looking Philadelphia, but what kind of city is it that can't keep two major league ball clubs?"

But many other letters were filled with gripes about the team's lackluster performance, the Macks' stinginess and the state of the ballpark. And many A's fans had grown apathetic.

"As for those agonizing A's, I admired them in 1904, but not in 1954," a fan from Philly wrote. "Let's have the Mayor's Committee plan how quickest to get rid of them. They are no credit to Philadelphia."

Wrote another: "Parting will be such sweet sorrow."

At varying points, there had been talks that the A's could be moved to Minneapolis, Dallas, Los Angeles and other cities. But an offer from businessman Arnold Johnson to buy the team and move it to Kansas City remained the most viable.

"Every day, it was a different story – they were gonna go, they were gonna stay," Taylor said. "It was still my favorite team. I liked the Phillies, but I was inbred as an A's fan, and it bothered me. I was 13 years old, and they were going to take my team away from me. That was a hard pill to swallow."

Connie Mack, shown in 1911, managed the Philadelphia Athletics from their inception in 1901 through the 1950 season. The A's won five World Series titles and nine American League pennants during his tenure, but also finished in last place 18 times.

The American League owners met in New York City on Oct. 12, 1954, in hopes of determining the A's fate.

Just weeks before, the Mack brothers had hinted that a refinancing plan would keep the Athletics in Philly for years to come. But it hadn't come to fruition.

The A's reportedly were in "dire financial straits," and several offers were on the table. They included Johnson's offer, which involved moving the team, and one that would have kept the A's in Philly for at least one more year.

The meeting lasted seven hours and had three recesses before the league approved the transfer of the A's to Kansas City. But Roy Mack insisted that he wanted to consult his family before finalizing a deal with Johnson, and he negotiated an out: If the Macks could raise $1.5 million within six days, they'd keep the team.

In the aftermath, a syndicate of eight Philadelphia businessmen emerged with a $4 million offer to purchase the A's. The Mack family would receive $1.5 million, but Roy would reinvest a portion of his payment to retain a stake in the A's and remain an executive.

Bruce Kuklick, who grew up attending Philadelphia A's games at Shibe Park, shows off his 1991 book on the ballpark, 'To Everything A Season.'

As the deal was being hammered out, a curious crowd gathered outside the Center City building where negotiations were happening. Once word got out that a deal had been agreed upon, Roy Mack reportedly received an abundance of congratulatory messages from all over the U.S.

"I have been waiting for this news all day," Connie Mack told the Inquirer. "Now I feel very good. I was sick at the thought that the club might leave Philadelphia."

The same enthusiasm was not necessarily felt outside of Philadelphia, and when the other American League owners reconvened, they failed to approve the deal. The Yankees, whose owners had ties to Johnson, had pushed heavily for the A's to move to Kansas City, and other clubs had grown tired of the low revenue they received when playing at Connie Mack Stadium.

The vote from the AL's eight teams was split, 4-4, in a secret ballot. Among those who reportedly opposed it: Roy Mack, though he denied it.

In a statement released by his wife, Connie Mack took aim at his son: "Roy Mack is the real fly in the ointment, no matter what he tries to feed the public. ... He has been behind everything since last May – telling everybody one thing and doing something else."

Shortly after the Macks had finalized their deal with the Philly syndicate, Roy Mack had met with Johnson. Johnson had sweetened his offer, and Roy had accepted it. He would get $450,000 for his stock and team positions for himself and son – just like in the syndicate deal – but the positions weren't dependent upon him reinvesting any money in the club.

With the Philly syndicate sale now dead, Connie and Earle Mack had little choice but to agree to the deal with Johnson, though a few members of the syndicate made a last-minute attempt at another agreement.

On Nov. 8, the AL owners approved the sale and the team's transfer to Kansas City. The $3.5 million deal bought out the Macks' stock, covered the team's debts and paid out the mortgage on the ballpark. Johnson then sold Connie Mack Stadium to the Phillies.

In the days that followed, legendary sportswriter Red Smith placed partial blame for the A's departure on baseball's changing economic conditions making it harder for cities to support multiple teams. Not long ago, he wrote in a syndicated column, teams could get by with a home attendance of 400,000. But with increased emphasis placed on farm systems and scouting, a gate approaching 1 million was necessary.

"There is bound to be a painful wrench when a team pulls up stakes – especially a team that has been such a landmark as the Athletics – but change is inevitable," Smith wrote. "Probably it's healthy, too. That is, a one-club town probably is better for baseball, in the long run, than a two-club town. Where there is only one team, interest is not divided, baseball becomes more truly a civic and community possession than it can be when two or more clubs are competing for the entertainment dollar."

In the years prior to the A's departure, the Boston Braves had moved to Milwaukee and the St. Louis Browns had headed to Baltimore to become the Orioles. The A's departure is unique among them for one reason.

"The most successful team left town," Taylor said. "It wasn't the Browns leaving St. Louis with their one stinking American League pennant. It was the Philadelphia A's with nine pennants and five world championships and a whole raft of Hall of Famers."

Three years later, the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants each bolted for California, continuing the trend.

At the Oakland Coliseum, the Shibe Park Tavern pays tribute to the A's days in Philadelphia. The bar includes an assortment of Philadelphia A's memorabilia and photographs.

"Baseball fans can't exist on memories of the good old days. They want a team that has a chance to win a game once in a while. The Athletics had grand old traditions, but precious little else. They had to go."

But to young, dedicated A's fans like Kuklick and Taylor, the loss was heartbreaking. They hadn't seen the A's at their height. They were just kids in love with baseball. Now, their favorite team had been ripped away.

"What I remember was just being very sad, because there were all of these campaigns to save the A's," Kuklick recalled. "The newspapers were saying, 'Please go out to see the team play. Show the baseball bigwigs that there's fan support.' And there wasn't. People just weren't interested in the A's anymore."

Kuklick said it took him "a long, long time" before he became a "devoted" Phillies fan – and his children had much to do with that. For years, he continued to follow the A's.

Taylor tells a similar story. He continued rooting for the A's well into their time in Oakland. When the A's came to Baltimore to play the Orioles in 1955, his stepfather took them to Memorial Stadium.

"It felt almost like an out-of-body experience. ... Because most of the players were the same," Taylor said. "The uniform looked a little different. But they were all there – (Gus Zernial) and all those guys. It was still the A's."

In the mid-1990s, Taylor helped found the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society, a former museum in Hatboro that once housed A's memorabilia, sold jerseys and gave A's fans a place to reminisce about their boyhood idols. At its peak, it had about 1,300 members, Taylor said.

"The reason the A's Society was as successful as it was is because a lot of people still were A's fans," Taylor said. "They hadn't given up on them."

For now, an homage to the Philadelphia A's can be found inside the Shibe Park Tavern at the Oakland Coliseum, the team's home since 1968. (The A's left Kansas City after 13 losing seasons.) Fans can sip beers while looking at ticket stubs, programs and other memorabilia from the franchise's days in Philly.

Beginning next spring, the Oakland Athletics plan to play their home games in Sacramento, California, until their proposed ballpark in Las Vegas opens in 2028. Their lease at the Coliseum ends at the end of this season, and a short-term extension was not reached.

A's fans have mostly stayed home since owner John Fisher announced he planned to move the team out of Oakland. The last-place A's are drawing only 7,731 fans per game this year, down 63% from 2019, when they finished 97-65 and averaged 20,626 fans per game. At the time, The A's were still using the slogan "Rooted in Oakland," which emphasized the club's commitment to building a new ballpark in the city.

Those that turn out haven't exactly been quiet. A segment of fans regularly brings banners and signs into the stadium, urging Fisher to sell the franchise. On Opening Day, thousands of fans purchased tickets but protested the team by watching the game from the parking lot. Last year, fans posed a "reverse boycott" — 27,000 bought tickets to a game in an effort to show the team's struggles were not the result of lacking fan support.

Just like when the A's left Philly, the franchise is leaving an extensive history behind. They won four more World Series, including three in a row in the mid-1970s behind Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter and Rollie Fingers. Rickey Henderson, Mark McGwire and Dennis Eckersley had memorable careers in Oakland. And, of course, the team's "Moneyball" era spawned baseball's analytics revolution.

"Moving them to Vegas, I think, is a terrible idea," Taylor said. "They should have found them a stadium in Oakland. ... Look at their record of championships and things, and how do you root them out of that city?

"(Fisher) doesn't grasp what he's doing. Baseball is a traditional sport, and that's one of the things that sells baseball – more so than a lot of other sports."

In time, Oakland A's fans will be left to ponder what might have been – as Philadelphia A's fans have done for decades.

"You can fantasize a lot," Kuklick said. "Imagine, what if the Phillies had left? ... If you still had the Philadelphia A's here, it would be, in some ways, remarkable. You would have a team with a really impressive history and record."

After all, it's been nearly 100 years since the A's won their last World Series in the city, and still no other Philadelphia sports franchise has won more championships.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center/Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Provided Image/Ted Taylor

Provided Image/Ted Taylor George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

George Grantham Bain Collection/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division Provided Image/Bruce Kuklick

Provided Image/Bruce Kuklick John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice